“The Whip-poor-wills now begin to sing in earnest about half an hour before sunrise, as if making haste to improve the short time that is left them. As far as my observation goes, they sing for several hours in the early part of the night . . . then sing again just before sunrise. … It is a bird not only of the woods, but of the night side of the woods.” Henry David Thoreau

By Troi Perkins

Every year, I am beset by spring fever as May’s budding trees burst with the familiar songs of avian migrants getting down to the business of nesting. This May, I was itching to be back out into the ‘field,’ to explore Vermont’s forests and lakes, when the opportunity came to work with the Vermont Center for Ecostudies (VCE) surveying for Eastern Whip-poor-wills. I leapt at the chance to scratch my spring fever itch. Hearing a Whip-poor-will had been on my bucket list since reading Henry David Thoreau’s account of the bird that’s “not only of the woods, but of the night side of the woods.” Little did I know that hearing one wasn’t as easy as Mr. Thoreau made it sound, nor did I suspect that I would end up trading my spring fever for Whip-poor-will fever.

I remember naively thinking it would be easy to detect a Whip-poor-will singing, with its distinctive sound. It turns out it’s not easy at all! Whip-poor-wills only sing at night, and even then the moon must be between it’s waning gibbous and waxing gibbous phase so that there’s at least 50% moon illumination. Therefore if it’s cloudy or raining, your chances of hearing a Whip-poor-will are very slim. On top of the weather conditions that can limit hearing a Whip-poor-will, you also have to be in the right habitat as well. Whip-poor-wills prefer sandy soils with large openings that have nearby pine dominated forests; an increasingly rare find in the ever changing landscape of Vermont.

I remember naively thinking it would be easy to detect a Whip-poor-will singing, with its distinctive sound. It turns out it’s not easy at all! Whip-poor-wills only sing at night, and even then the moon must be between it’s waning gibbous and waxing gibbous phase so that there’s at least 50% moon illumination. Therefore if it’s cloudy or raining, your chances of hearing a Whip-poor-will are very slim. On top of the weather conditions that can limit hearing a Whip-poor-will, you also have to be in the right habitat as well. Whip-poor-wills prefer sandy soils with large openings that have nearby pine dominated forests; an increasingly rare find in the ever changing landscape of Vermont.

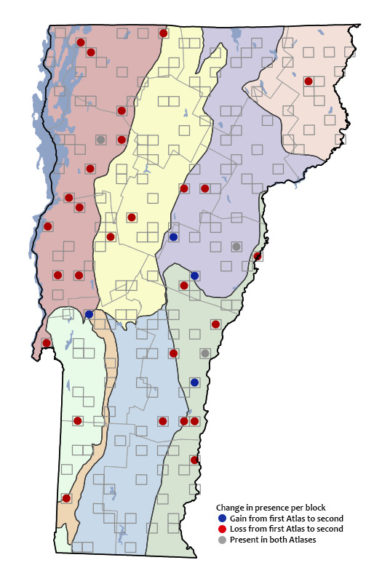

For years, volunteers have adopted survey routes around Vermont in an effort to monitor this elusive species, whose population has dramatically declined in Vermont. For the last three years, VCE and Vermont Fish and Wildlife have teamed up to complement the volunteer surveys.

Beyond the typical challenges a birder might encounter in seeking a Whip-poor-will, scientific surveys adds some additional complications. This year’s official Eastern Whip-poor-will survey spanned just 30 nights spread across May, June, and July, corresponding to moon phases favorable for the birds’ singing habits. This spring’s streak of cloudy and rainy weather reduced our 30-night survey window by nearly half. Winds over 8 mph will stop a survey dead in its tracks while loud highway noise or dogs barking can severely limit a Whip-poor-will’s detectability by drowning out their song. With time short and so many factors at play, I was one nervous field tech!

Despite the formidable odds, I joined my colleague Sarah Carline to cross the state in search of the elusive Whip-poor-will. Our adventures began close to home, with two 9 miles stretches spanning from Randolph to South Tunbridge. While Vermont eBird shows very few recent sightings in these locations, (just 5 in the past 6 years), the habitat was right and thus the potential was there to find a Whip-poor-will. Periods of clouds and and high wind speeds plagued us, repeatedly postponing the survey. While we eventually completed both routes, we found no “Whips.” With five surveys nights down, just 25 remained for me to satisfy my personal goal of hearing my first Whip-poor-will.

June offered just 17 potential survey nights with the first three foiled by clouds. On the fourth night we drove to Orwell, in southern Addison County, but as we set out, wind came howling down the mountains and slammed our survey window shut. We quickly switched gears and traveled to the nearby Wells route, which would be more sheltered from the wind. Wells is a landscape marked by slate quarries, remnants of the 1850’s slate industry that is still going strong today. On a quiet road among the quarries, the moon shook free of the clouds and the wind quieted to a gentle breeze. All of a sudden, a silhouette crossed the starry sky a couple hundred feet in front of me. A small bird had flown from the ridge to my left, crossing over to a hollow on my right. Before I could muster the words to alert Sarah, an utterly new, yet somehow familiar, sound accosted my ears: the song of an Eastern Whip-poor-will. It lasted only a brief 30 seconds before the clouds took the moon hostage again yet it left me awestruck. Braving the clouds and wind, this little bird made the most of a few brief, clear moments and sang its heart out until the moon was covered once more.

But I was not satisfied! I wanted to hear more than just a 30 second song from one bird. I wanted more Whip-poor-wills. Spring fever was out; Whip-poor-will fever set in.

Twelve survey nights remained, including a week in July. We travelled to Ferrisburg, Pawlet, Orwell, Randolph, South Tunbridge, and back to Wells. We camped at several state parks from Button Bay, to Half Moon Pond, and even Lake St. Catherine. This extensive travelling also came with survey downtime; downtime that helped to sait my spring fever with periods of loon surveying and bird watching. However my whip-poor-will fever was still raging.

All told, we surveyed a total of 161 points. We heard 10 more Whip-poor-wills, 3 of which were singing on the New York side of Lake Champlain. Each of those sleepless nights was rewarded with beautiful views, observations of some of the 55 total bird species seen on our survey, and of course the occasional Eastern Whip-poor-will song. In fact hearing the Barred Owls, Song Sparrows, Killdeer, Ovenbirds, and Wilson’s Snipe just added to the overall experience. Now, I find myself eagerly awaiting the next sunrise or sunset for yet another chance to hear a Whip-poor-will singing. My spring fever may have been cured — for now — but in return I contracted a case of Whip-poor-will fever to last a lifetime.

To come down with your own case of Whip-poor-will fever, consider joining VCE’s Vermont Whip-poor-will project next year. Check out the project description and contact the project’s lead biologist Sarah Carline to adopt one of the Whip-poor-will survey routes in the state of Vermont.

Learn More About Eastern Whip-poor-will

- You can listen to an episode of Outdoor Radio about Vermont’s Eastern Whip-poor-wills and hear their amazing calls.

- Results from the Vermont Breeding Bird Atlas, a project of the Vermont Atlas of Life

- Map of sightings on Vermont eBird, a project of the Vermont Atlas of Life.

Love this research. We have at least 1 that returns each year, we sit out often to listen to it. Not sure if it’s calling for a mate or protecting a nest. Came here to seek that answer.