a strange mating system

a strange mating system

Spurred by an incidental observation of two color-banded males sequentially feeding young at a Stratton Mountain nest, we delved further by placing video cameras at nearly one hundred nests to identify feeders (watch a female feed her nestlings). Then we analyzed mitochondrial DNA of nestlings and adults. To our and many others’ great surprise, we found that two to as many as four males attended 75% of the nests, but never more than a single female did so. Coincidentally, we learned that males do not hold traditional territories but wander widely over home ranges of up to 20 hectares (50 acres), each bird broadly overlapping its movements with those of up to seven other males. Females, in contrast, occupy and defend much smaller, non-overlapping territories. The plot thickened when we analyzed paternity, which was highly mixed in 70% of nests. In short, both male and female Bicknell’s Thrushes mate with multiple partners, some males feed multiple broods concurrently, some males feed broods in which they have no paternity, and females on higher quality territories (as defined by arthropod prey biomass) fledge more chicks and have fewer males feeding them. This complex breeding system, termed “female-defense polygynandry,” is known in only one other North American songbird, Smith’s Longspur.

- Goetz, J.E.., K. P. McFarland and C.C. Rimmer. 2003. Multiple paternity and multiple male feeders in Bicknell’s Thrush (Catharus bicknelli). Auk 120: 1044-1053. (Abstract)

- Strong, A.M., C.C. Rimmer, and K.P. McFarland. 2004. Effect of prey biomass on reproductive success and mating strategy of Bicknell’s Thrush (Catharus bicknelli), a polygynandrous songbird. Auk 121:446-451. (Abstract)

Balsam fir: A keystone species

Balsam fir: A keystone species

We have discovered a biennial cycle involving balsam fir cone mast, red squirrels and possibly other small mammals, and bird demographics. We annually monitored balsam fir reproduction, bird densities and reproductive success, and red squirrel densities. High cone production occurred biennially in late summer and fall of even-numbered years and was followed by immigration and breeding by White-winged Crossbills, Pine Siskins and red squirrels. Open cup-nesting birds experienced extremely low rates of nest success in summers following heavy cone mast, probably due to nest depredation by red squirrels and other small mammals, and high success following mast failures. Analysis of demographic variables indicates that our study populations are sinks in odd years, sources in even years, and barely break-even overall.

- McFarland, K.P. 2003. A Good Year for Fir Cones. North Woodlands Magazine – Outside Story.

songbirds and ski area development

Overall, few significant differences existed for various population and reproductive parameters between areas developed for ski areas and natural forests on each mountain. We found no evidence that nest predation rates differed between ski area and natural forest plots, or that nests in either plot type were more likely to be depredated. Despite higher nest densities near ski trail edges, it appears that edge effects do not exert an important influence on rates of nest predation for Bicknell’s Thrush, and that the ‘ecological trap’ hypothesis does not apply to this species in existing ski areas. There was no evidence that female brooding behavior, male feeding behavior, or movements of adults differed between ski areas and natural forests, although our study design did not specifically address these issues. Finally, we found no significant differences in adult survivorship, nest success, or breeding productivity of Bicknell’s Thrushes between ski areas and natural forests, although a power analysis suggested that survival probabilities for adult males were somewhat lower in ski-slope edge habitats. Findings from radio telemetry of adult thrushes indicated that trail crossings wider than 50 meters (m) were avoided, and that small or narrow habitat islands were rarely used. As a general rule, ski trails greater than 35-40 m in width appear likely to restrict thrush movements. Breeding thrushes were concentrated in habitat blocks consisting of fairly large, closely adjoining islands intersected by narrow, winding ski trails; these were often separated by large open areas. Habitat configurations that featured alternating narrow, linear slopes and islands tended not to support clusters of Bicknell’s Thrush home ranges. This suggests that trail design should maximize habitat contiguity and minimize fragmentation to promote suitable features for Bicknell’s Thrush. Fewer, larger islands separated by narrow, non-linear trails are preferable to larger numbers of small islands or alternating bands of linear trails and islands.

- Rimmer, C.C., Kent P. McFarland, J. Daniel Lambert, and Rosalind B. Renfrew. 2004. Evaluating the use of Vermont ski areas by Bicknell’s Thrush: applications for Whiteface Mountain, New York. Unpublished report. (PDF)

- Strong, A. M., C. C. Rimmer, K.P. McFarland and K. Hagan. 2002. Effects of mountain resorts on wildlife. Vermont Law Review 26(3): 689-716. (PDF)

Bicknell’s thrush habitat and climate change

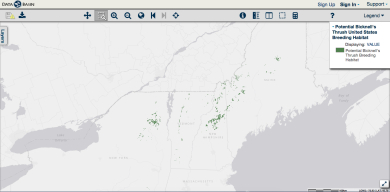

Click on the map to visit DataBasin where you can use an interactive map of potential Bicknell’s Thrush habitat and download data for your GIS.

For the first time, we can reliably predict where Bicknell’s Thrush breeding habitat is located in the northeastern United States. This information is in great demand from natural resource agencies, conservation groups, and those who own land in the high country. The map identifies potential habitat by integrating three layers of geographic information: forest type, elevation, and latitude. It shows nearly 340,000 acres of red spruce and balsam fir forest in mountainous regions of New York, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. In a test of the map’s accuracy, it proved to be 85% to 98% correct in predicting the presence or absence of Bicknell’s Thrush along 1-km survey routes.

This map helps to identify opportunities to conserve critical habitat and it provides a basis for evaluating plans to develop mountain areas. It also allows us to examine what might happen to this habitat in the future under different climate change scenarios.

Global warming is poised to substantially change the climate in the Northeast if heat-trapping emissions are not curtailed, and the extent and impacts of the change depend on the choices that governments, businesses and citizens make today. By the end of this century, for instance, summers in Vermont could feel like those in Tennessee if emissions continue unabated. But if emissions are reduced, summers in Vermont could resemble those of West Virginia. So concludes the study released by the Northeast Climate Impacts Assessment, a collaboration between the Union of Concerned Scientists and a team of independent scientists from universities across the Northeast and the nation, including VCE biologists.

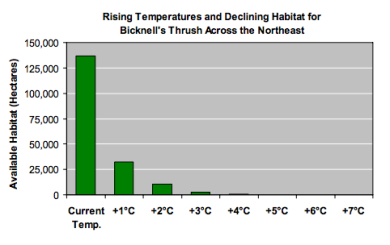

Under the rising mean summer temperatures examined by the VCE biologists, the spruce-fir zone literally loses ground. Warming climate causes the lower boundary of this zone to gradually retreat up the mountain. The spruce-fir forest and its suite of plant and animal communities are therefore limited to progressively higher, smaller, and more isolated patches.

Our research shows that the most vulnerable species may be those that, like the Bicknell’s thrush, depend on high elevation spruce-fir habitat. Under either low or high emissions scenarios, great losses in suitable habitat are expected for this rare songbird as a result of climate changes projected this century. Only under the lower-emissions scenario is this range-restricted species projected to retain more than 10 percent of its U.S. habitat. Mountain-breeding populations of spruce grouse, three-toed woodpecker, black-backed woodpecker, gray jay, yellowbellied flycatcher, boreal chickadee, and blackpoll warbler are expected to be similarly affected.

- A summer temperature increase of roughly 4°F, projected by mid-century under either emissions scenario, may be enough to eliminate all breeding sites for the Bicknell’s thrush at the southern edge of its range in the Catskill Mountains of New York and most of Vermont.

- With summer warming of 9°F, projected under the higher-emissions scenario by late this century, only small patches of suitable habitat for the Bicknell’s thrush may remain in New Hampshire’s Presidential Range and on Mount Katahdin in Maine.

- If summers warm by 11°F, also possible by late in the century under the higher-emissions scenario, suitable habitat for the Bicknell’s thrush is expected to disappear from the Northeast.

- In the Berkshires of Massachusetts and the Allegheny Plateau in Pennsylvania, encroachment of hardwoods into mountaintop spruce/fir forests (projected as late century warming reduces spruce/fir habitat) would threaten the remaining small populations of such species as the blackpoll warbler and yellow-bellied flycatcher. Further north, these species are less vulnerable because they occur in both high- and low-elevation spruce/fir forests.

Science Publications

- Lambert, J. D., K. P. McFarland, C. C. Rimmer, S. D. Faccio, and J. L. Atwood. 2005. A practical model of Bicknell’s Thrush distribution in the northeastern United States. Wilson Bulletin 117:1-11. (Abstract) Winner of the Ernest P. Edwards Prize for the best major article published in The Wilson Journal of Ornithology in 2005.

- Rodenhouse, N.L., S.N. Matthews, K.P. McFarland, J.D. Lambert, L.R. Iverson, A. Prasad, T.S. Sillett, and R.T. Holmes. 2008. Potential effects of climate change on birds of the Northeast. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 13: 517-540. (Abstract)