Why We Can’t Call the Bicknell’s Thrush Race Yet: A Peek Into How Migration Monitoring Works

Freddy Wet-foot with his backpack tag, by our seasonal bird bander Anna Peel.

You might have noticed we’ve been pretty quiet about the results of the Bicknell’s Thrush Race to the Atlantic. That’s because we’re not totally sure which bird won. Yes, we know of two birds that migrated past a coastal tower and out over the water at night: Trap-Happy Travis on October 15th, and Tiny Tim on October 21st. But there’s a chance other birds left earlier.

Let me provide some context for what is going on.

Over the last two decades, the technological advancements in tracking small migratory animals have been staggering. Ten years ago, we would have had to wait nearly an entire year to know which tagged bird was the first to take flight over the water. A few years before that, it would have been impossible to know. Today, we can push a button and, in many cases, see where individuals were last detected in near real time.

That is thanks to The Motus Wildlife Tracking System, a program of Birds Canada in collaboration with an international network of partners. It’s a global, collaborative research network that uses automated radio telemetry to track the movements of animals, including birds, bats, and large insects. Researchers attach small, digitally-encoded radio tags to migratory animals, such as Bicknell’s Thrush. As individuals migrate or go about their daily routine, they are detected by receiving stations across the landscape, which are independently hosted by individuals, schools, education centers, and others.

The towers vary in configuration, but all are composed of a few key elements. They have at least one antenna to detect coded tags, but often three or four are pointed in different directions to maximize detection. Each antenna is connected to a receiving station that stores the data.

The receiving stations constantly scan the horizon for coded tags, but their detection range is limited, varying by location and physical obstacles, such as trees, buildings, and topography. Therefore, individuals are most likely to be detected by a station when they fly or forage within approximately 15 kilometers of the tower. With a clear line of sight and perfect conditions, tags much farther away may be detected, but the opposite is also true: some antennas may only reach a few hundred meters.

At a minimum, the receiving stations store the data on the unit. However, the data need to be filtered to remove an individual’s coded signal from other radio noise. To do that, the data recovered by the receiver are uploaded to the Motus Network so researchers and others can re-create individuals’ movements.

How the stations upload data also varies widely. The best places to install Motus towers to track migratory movements aren’t always in areas with high-speed internet and electricity. Many towers are powered by solar panels, and are in remote places like barrier islands or in the middle of a salt marsh, where obtaining or uploading the data can be logistically challenging. Some towers scan the horizon for an entire year before the tower can be visited and the data manually downloaded. Other towers are more seamless, like the tower we deployed at Reserva Zorzal in the Dominican Republic. It’s connected to high-speed internet, and uploads and makes data available daily.

As you can imagine, other factors limit data availability as well. For example, if a station is hosted by the federal government, such as one on a national wildlife refuge or a building maintained by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, government shutdowns can delay data uploads.

Many of the coastal towers that have detected Bicknell’s Thrush in previous years—as they depart the shores of the United States for the Caribbean—are located on remote barrier islands with limited internet access, and/or they’re hosted by the federal government.

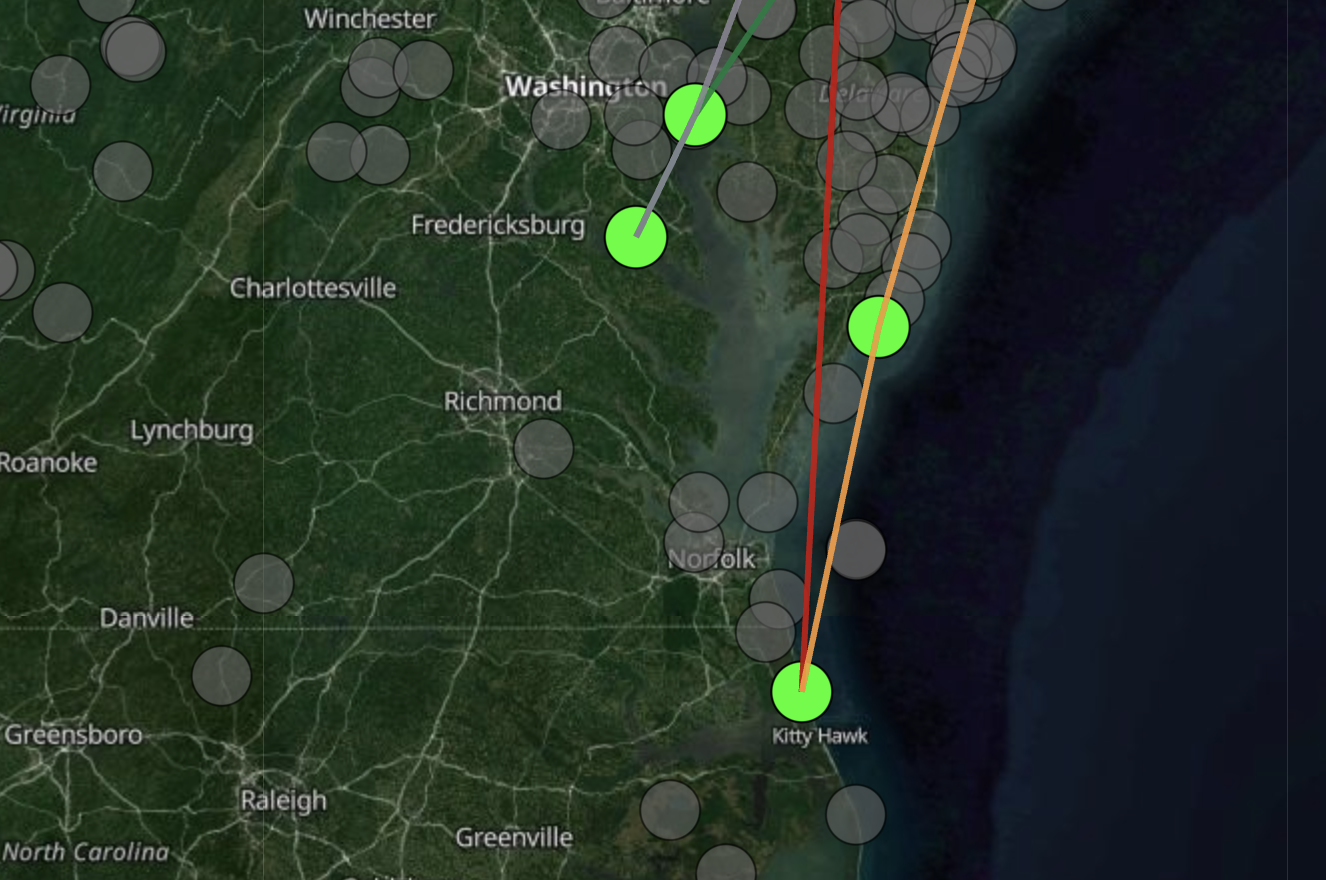

The grey and green spots indicate Motus towers. The green spot north of Kitty Hawk indicating the Pine Island Audubon Sanctuary saw two of our tagged birds fly by at night on their way out to sea. The tower to its south on Pea Island usually sees a lot of Bicknell’s Thrushes migrate by in the fall. We’re waiting on its data to be uploaded and processed.

The Motus tower at Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge is a prime example. Located just south of the tower that detected two of our Bicknell’s Thrushes in October, the Pea Island tower has detected dozens of migrating Bicknell’s Thrushes over the years—individuals tagged in the Dominican Republic, on Mount Mansfield and Mount Washington, and in Canada. But early September was the last time data were uploaded from Pea Island, just before the government shutdown. There’s no way for us to know who was detected on that key tower, and others like it, until data from this fall become available.

So that leaves us where we are today: Ten of the 19 Bicknell’s Thrushes we tagged on Mount Mansfield this summer pinged towers at least once between September 21 and October 21. Of those, two pinged a coastal tower on North Carolina’s barrier islands at night, on their way out to sea. Others were last seen in New Jersey, Connecticut, and Massachusetts. Nine have not yet been detected on any of the towers that are regularly reporting data.

We don’t know what happened to the 17 birds that didn’t pass by a coastal tower at night. It’s possible that they migrated from Mount Mansfield to Hispaniola, avoiding towers all the way. They could have pinged Pea Island or another tower that hasn’t uploaded data in the past two months. They could have lost their tag. They could have died.

The latter is common, especially during migration when mortality is greatest. The annual survival rate for Bicknell’s Thrush ranges from 40% to 75%, with an average of about 50%. That means that every adult bird has about a fifty-fifty chance of surviving their entire annual cycle. Much of our current research aims to determine where and why birds are dying.

Rest assured that if a key coastal tower detected your favorite Bicknell’s Thrush, we’ll know . . . eventually. Luckily, we have some great partners across the Motus network who are going to check on those key towers for us.

We had hoped to call the race and send out winning merch before the end of the year, but good science doesn’t always hew to our human schedule. We’ve decided instead to wait until the Pea Island data are uploaded and processed, which hopefully will be sometime in the next two weeks. Then we’ll call it with confidence and let you know.

The Motus Wildlife Tracking System is a program of Birds Canada in collaboration with an international network of partners.

The Motus Wildlife Tracking System is a program of Birds Canada in collaboration with an international network of partners.

Very interesting. I am still betting on balsam Betty!!!

I so enjoyed being on mt Mansfield during a banding session a couple years ago with Chris Rimmer. And crew. Thanks.

Well-done all at VCE who came up with this very creative, fun, and informative way to raise funds for your Bicknell’s Thrush program! We learned a lot about the Motus tracking system and the challenges of getting good migration data, but more importantly I think, this “race” made the hazards of migration all the more real. I thought about the birds during the hurricane and have worried for Dr. Dimmer and his cohort between news updates. Thank you for a wonderful (albeit stressful) way to connect with migrating birds and all that they face.