Not long ago, the Yellow-banded Bumble Bee was among eastern North America’s most common bumble bee.

Although absent from most its range since 2000, recently Yellow-banded Bumble Bee has been found in northern parts of its range, including Vermont during VCE's statewide survey in 2012 and 2013.

NATURAL HISTORY

Bumble bees are essential pollinators of crops and wildflowers in agricultural, urban, and natural ecosystems. They play an important role in the reproduction of tomato, blueberry, pepper, cranberry, clover, apple, and many other crops.

Yellow-banded Bumble Bee lives in colonies consisting of a queen (foundress) and her offspring, the workers, and near the end of the season the reproductive members of the colony, the males and new queens. There is a division of labor among these three types of bees. The foundress is responsible for initiating colonies and laying eggs. Workers are responsible for most food collection, colony defense, and feeding of the young. Males leave the nest once they reach maturity and their sole function is to mate with queens. New queens remain with the nest until the end of the season when they leave to mate and find hibernacula. Colonies are annual, progressing from colony initiation by solitary queens in spring, to production of workers, and finally to production of queens and males.

It is one of the earliest Bombus species to emerge, with observations of queens as early as March and April in some areas (Colla and Dumesh 2010). The foundress begins searching for suitable nesting sites and collects nectar and pollen from flowers to support the production of her eggs, which are fertilized by sperm she has stored since mating the previous fall. In the early stages of colony development, the queen is responsible for all food collection and care of the young. As the colony grows, workers take over the duties of food collection, colony defense, and care of the young. The foundress then remains within the nest and spends most of her time laying eggs. New queens and males are produced during the later stages of colony development, which is generally from mid-July to September (Plath 1922; Milliron 1971; Macfarlane et al. 1994). This species may be particularly susceptible to stressors because it emerges so early, but does not produce the next generation until late in the summer. The new queens mate before entering diapause. Only the new, mated queens overwinter; males, founder queens, and all workers perish with autumn freezing temperatures.

Nest sites may be limited by the abundance of rodents. Although little is known about the overwintering habits of the queens, other species frequently dig a few centimeters into soft, disturbed soil and form an oval shaped chamber in which they will spend the duration of the winter. Compost in gardens or molehills may provide suitable sites for queens to overwinter (Goulson 2010).

Bumble bees are particularly vulnerable to extinction due to their complementary sex determination system and haplodiploid life history (Zayed and Packer 2005). Loss of genetic diversity, which is frequently the result of inbreeding or random drift, can pose significant threats to small, isolated populations of bumble bees (Whitehorn et al. 2009). A loss of genetic diversity limits the ability of a population to adapt and reproduce when the environment changes and can lead to an increased susceptibility to pathogens (Altizer et al. 2003).

THE DECLINE

Until recently, Yellow-banded Bumble Bee was broadly distributed across the eastern U.S. and Upper Midwest, north through southern Quebec and into Newfoundland in Canada, south along the Appalachian Mountains to the northeast corner of Georgia, reaching west into the mountains of British Columbia and formerly in the northern Rocky Mountain states. Studies since the late 1990s have indicated a range contraction and decline of populations.

Although the Yellow-banded Bumble Bee was historically distributed throughout the Upper Midwest, Northeast and Eastern Seaboard, recent range-wide studies have estimated that B. terricola has declined by ~50% (Williams and Osbourne 2009, Colla et al. 2012), and warrants “endangered” status under IUCN protocols (Williams and Osbourne 2009).

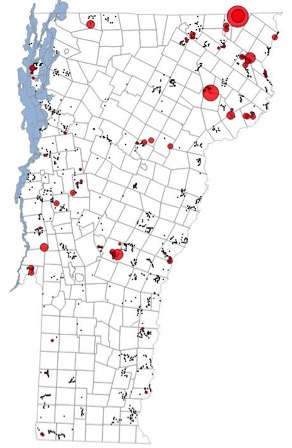

Historically, Yellow-banded Bumble Bee appeared to be a common component of the Vermont bee fauna. Regional data suggest that it was probably found throughout the entire state. The Vermont Bumble Bee Survey assembled nearly 2,500 Bombus records from 1915 to 2011 from over 25 collections (Vermont Center for Ecostudies unpub. data). It represented about 13% of the records (n=315), the 2nd most common species of 17 known species in Vermont. Two biologists, Bernd Heinrich and Leif Richardson, noted a severe population decline in 2000 with few observations of the species until 2007 when perhaps a slight recovery began. In 2012, the Vermont Bumble Bee Survey found just 26 B. terricola out of 5,053 specimens (0.5%) and 66 (~1%) of more than 5,000 specimens in 2013. It was found at just 73 out of over 1,500 survey sites during the two-year survey. B. terricola was encountered rarely in southern Vermont, in widely scattered locations in the Champlain Valley and central Vermont, and more widespread in the Northeast Kingdom region.

Relative abundance of Yellow-banded Bumble Bee found during the Vermont Bumble Bee Survey (2012-2013). Red circles indicated total observations on each survey from 1 (small circles) to 8 (largest circles) individuals. Black dots are surveys in which none were found.

In 2012, VCE’s Vermont Bumble Bee Survey found just 26 B. terricola out of 5,053 specimens (0.5%) and 66 (~1%) specimens in 2013. It was found at just 73 out of over 1,500 survey sites during the two-year survey. B. terricola was encountered rarely in southern Vermont, in widely scattered locations in the Champlain Valley and central Vermont, and more widespread in the Northeast Kingdom region.

Research has indicated that declines in North American bumble bees have been associated with increased levels of pathogen infections and reduced genetic diversity (Cameron et al. 2011). Also, habitat loss or degradation, pesticides, climate change, and competition with honey bees may have contributed to the range-wide decline of this species.

The Yellow-banded Bumble Bee is not alone. At least five other species of North American Bombus have undergone severe range reductions, including three species found in Vermont- Rusty-patched Bumble Bee (B. affinis), Ashton Cuckoo Bumble Bee (B. ashtoni), and American Bumble Bee (B. pensylvanicus); and two species in the West: Franklin’s Bumble Bee (B. franklini) and Western Bumble Bee (B. occidentalis). Like B. terricola, many of these species apparently declined drastically in the 1990s. Although the causes are not fully understood, they are likely to be the same culprits for the entire Bombus fauna: introduced pathogens and parasites, habitat change or loss, pesticides, and climate change.

CONSERVATION ACTION

The Yellow-banded Bumble Bee has been proposed to be listed as ‘Threatened’ in Vermont. Any management or regulations aimed at the protection and recovery of B. terricola will undoubtedly help the conservation of the entire Bombus fauna. Some of these might include examination and changes of neonicotinoid pesticide use and regulation, the spread of pests and diseases by the commercial bumble bee industry, land management specific to bumble bee conservation, or perhaps one day discovering and promoting populations that are resistant to introduced pathogens.