A Field Guide to April 2017

Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) in full April bloom. / © K.P. McFarland

In April the northern forest is bare with cold desire. Blades of wild leeks slice through the soggy, brown remains of autumn to release sweet-onion perfume. Bright white Bloodroot opens for wild bees. A Ruby-crowned Kinglet sings with his head ablaze. Spring Peepers burst forth in the evening with up to 4,000 peeps an hour. The sweet smell of soil rises to our nose. Streptomyces bacteria awaken as the soil warms and spew chemical weapons against other bacteria, which to us has a distinct earthy smell. April leaves none of our senses void. Here’s our guide to some of the joys of April.

A Field Guide to the Sky Dance

A sign of spring for us is an evening trip to the theater to watch what Aldo Leopold called the sky dance in his 1949 classic A Sand County Almanac. Our theater has no roof and no seats. It’s just a small field next to a shrubby wetland near our house with a show that is something to behold. It’s the annual courtship flights of the American Woodcock and this year on a crisp, clear night it was an especially beautiful show.

The dancers in this annual show have a long bill with a flexible tip specialized for probing and capturing earthworms, a stout head with large eyes set far back for rearview vision without a mirror, and plumage with mottled, leaf-brown patterns that blend superbly with the forest floor.

The theaters they use are made of moist woodlands or thickets near fields or open areas. The audience is encouraged to arrive early and remain quiet while they let their eyes slowly adjust to the dimming light. The curtain usually opens with the male woodcock flying onto the stage at exactly 22 minutes after sunset when the lights are dimmed to precisely 0.05 foot-candles. With the crowd hushed, the dancers begin.

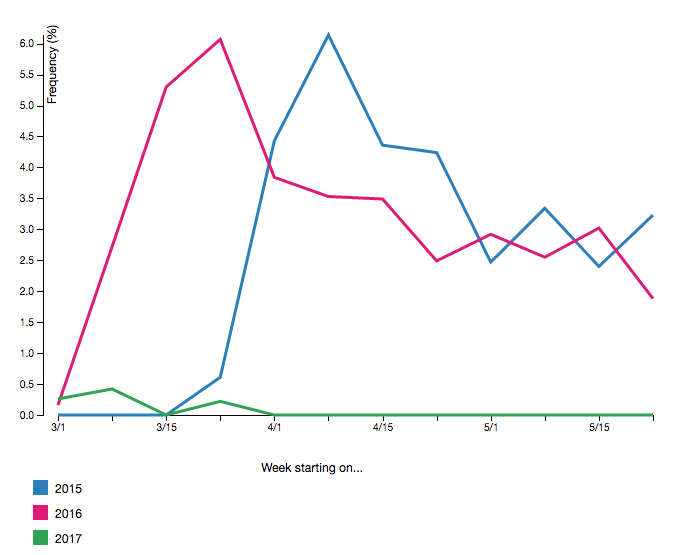

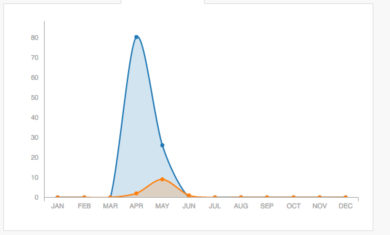

American Woodcock phenology from Vermont eBird. With a warm spring in 2016, observations peaked on March 22. They didn’t peak until April 8 during the cold spring of 2015. What’s in store for us this year in Vermont? It is looking like a late spring. Add your observations to Vermont eBird and help track their phenology. Click on the chart to explore more.

The males are loosely clustered about the stage. Each defends a small area on the ground were the peent, a short (~0.2 seconds) buzzy note is repeated over and over. If you are close enough you can also hear each peent preceded by a short (0.3 seconds) tuukoo, wukoo or ka-rurr sound. The two sounds often merge into one, tuukooeeent. He may also givetuukoo calls at widely separated intervals (0.2–30 seconds) initially after alighting on display area or when alert to strange sounds.

The sky dance begins when the “peenting” bouts end. There are five parts to the flight:

- a silent, gradual ascent lasting about 2 seconds;

- a continued gradual ascent with light wing twittering for about 12 seconds;

- the wing twittering becomes melodious as he climbs steeper and then loops into spirals for about 15 seconds;

- the apex of the flight lasts for about 12 seconds and may be 300 feet high, as the wing twittering becomes intermittent with rapid, short bursts, overlapping with loud, vocal chirping during the initial descent as he zig-zags, dives, and banks, then pitching down again precipitously;

- a silent descent lasts up to 8 seconds as he brakes to the ground with soft but audible flapping wings and lands back on his stage to resume another bout of peenting.

The twittering sound is produced by air passing between three attenuated outer primary feathers on the wing. The outer primaries of a male American Woodcock are narrowed (called emarginated), which produces whistling twitters during the sky dance. The chirping calls made during the sky dance are a fast, repetitive series of 4–6, melodious notes – chirp-chirp-Chirpchirpchirp, repeated.

Sometimes they will give a rapid, harsh cackle, ca-ca-ca-ca-ca , as they fly low over another peenting male. Cackling is probably an aggressive challenge. Sometimes the peenting bird may chase the aggressor and cackle back. If two peenting males are too close to each other, they may give aggressive cackle calls on the ground too.

As many as 24 sky dances can be performed by an individual during an evening performance, but most average a half dozen per night. As twilight disappears from the western sky, the performers retire for the night and wait for the curtain to rise in the dim light of the morning for another bout of sky dancing.

After a Long Winter Nap, Butterflies Take Flight

After a long winter nap in a crack or hollow tree, they’re awakening. The slumbering brushfoots, Mourning Cloaks and Anglewings, flit about on sunny April days. And we hope you add all of your butterfly observations to e-Butterfly.org. How’d they survive the winter? Read my essay on the Butterflies of Winter on Outside Story.

Fireworks Above the Mud

Not to be outdone in this burst of crimson is Beaked Hazelnut. If you walk too fast, splattering mud along the trail or searching for the season’s first Hermit Thrush, you will miss the show. Slow your pace, watch for a gray shrub not much taller than you. The drooping catkins are your first hint. But cast a careful gaze for that April explosion. VCE research associate, Bryan Pfeiffer explains more.

Wild for Wildflowers

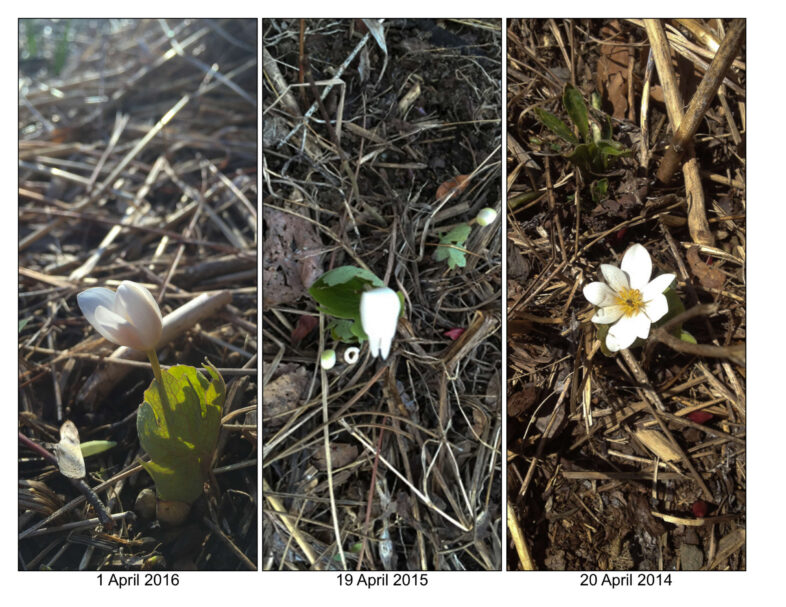

The same Bloodroot plant monitored for three years flowered nearly three weeks earlier last year. / K.P. McFarland

Last spring was the warmest on record for the continental U.S. in 121 years of record keeping. And with that, spring sprung early. I have monitored the first flowering of Bloodroot, a native spring ephemeral wildflower, in my yard for the past three years. I take a photo of the first flower each year and upload it to iNaturalist Vermont, a project of the Vermont Atlas of Life, using an iPhone and the iNaturalist app. Last year, it flowered nearly three weeks earlier than the past. What will this year bring? You can help monitor flower phenology too.

Spring ephemeral wildflowers are perennial woodland plants that sprout from the ground early each spring, quickly bloom and seed before the canopy trees overhead leaf out. Once the forest floor is deep in shade, the leaves wither away leaving just the roots, rhizomes and bulbs underground. It allows them to take advantage of the full sunlight levels reaching the forest floor during early spring.

Long-term flowering records initiated by Henry David Thoreau in 1852 have been used in Massachusetts to monitor phenological changes. Phenology, the study of the timing of natural events such as migration, flowering, leaf-out or breeding, is key to examine and unravel the effects of climate change on ecosystems. Record-breaking spring temperatures in 2010 and 2012 resulted in the earliest flowering times in recorded history for dozens of spring-flowering plants of the eastern United States.

Help Monitor Wildflower Phenology

We have the opportunity to start long-term monitoring across Vermont. We’ve chosen 10 common spring ephemeral wildflowers for everyone to monitor. Find a plot to monitor in a forest near you or simply record the status of those you find around Vermont. You can enter your observations on our site at iNaturalist Vermont. Please include a photograph(s) of the plant and in the box next to “Add a field” type in Flowering Phenology (select bare, flower, or fruit).

Focal Wildflowers (click to learn more about each at iNaturalist Vermont):

Trout Lily (Erythronium americanum)

Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis)

Marsh Marigold (Caltha palustris)

Spring Beauty (Claytonia caroliniana)

Red Trillium (Trillium erectum)

Painted Trillium (Trillium undulatum)

Starflower (Trientalis borealis)

Dutchman’s Breeches (Dicentra cucullaria)

Squirrel Corn (Dicentra canadensis)

Jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum)

From barely a Peep to CACOPHONY

It’s a warm spring evening. The sun has set. Down in the valley, there is a chorus erupting, and up on the hill in a pond, another is just beginning. The spring peepers are in stereo. Spring has finally sprung.

The cacophony is emanating from hundreds of male spring peepers. Each peep is made when a frog forces air from its lungs, over the vocal cords in the larynx, and into an air sac in its throat. The air enters the sac from openings on each side of the mouth cavity, causing the sac to balloon outward. The inflated sac acts as a sounding board, amplifying the sound and carrying it from the frog to my ears across the valley.

What sounds like chaos to me sounds organized to a peeper. Several males may interact vocally by forming duets, trios, or quartets, with alternating peep calls and individual notes. When males alternate calls, one individual, the follower, usually calls within 40 to 70 milliseconds from the end of the leader’s call.

Males tend to stay within a close pitch range of each other. The spacing and timing of calls accentuates the distinctiveness of each male’s call so that it is not lost in the overall din and allows a female to zero in on a single calling male. When another male frog moves too close, one male may use a second type of call, a trill. The trill seems to reflect a higher degree of aggression than the peep call and will stimulate one of the individuals either to move away or perhaps to trill back in challenge, causing a trill-off. A trill-off can escalate into a brief physical scuffle, with the winner staying and the loser moving on to quieter waters.

Each male peeper can pump out from 3,000 to 4,000 peeps an hour for several hours each night. So it is not surprising that male trunk muscles, which help propel air from the lungs, average 15 percent of their body mass compared to only 3 percent for the quiet females. Aerobic capacity of trunk muscle is six times that of leg muscles and, in males, is 17 times greater than that of female trunk muscle. Peepers derive about 90 percent of their energy for call production from fat reserves in these muscles. Males weigh on average about the same as two dimes, yet their sound pressure is comparable to the song of a warbler (about 4 quarters in weight) or a blackbird (a whopping eight half-dollars in weight). These little peepers have big bellows.

The peeper mating system is based on female choice. The louder and faster he peeps, the better his chances of attracting a receptive female. When biologists played recorded peep calls for female peepers, the females preferred peep rates double those found in the wild, indicating a strong sexual selection for males that can peep fast. Male peepers, therefore, push their singing abilities to the limit, performing at or close to their full physiological capacity. But one night of binge calling doesn’t seem to wear them out: males that have the higher peep rates in one night tend to have higher peep rates every night.

The evening temperature can affect calling patterns. On warmer evenings, peepers call much more frequently. The consumption of oxygen increases with calling rate, which in turn increases with temperature. At a balmy 60°F, peep calls are repeated up to 13,500 times per night.

Not all males sing, though. A big chorus of singers will also attract a host of silent males, who mix in around the edges. These shy guys tend to be smaller than the big singers. They quietly wait near a good singer, watching for a female that may be attracted to a peeping male. When she comes along, they use their quickness and agility to beat the singer to the female.

According to the Vermont Amphibian and Reptile Atlas, peepers can begin calling as early as March 15, with peak activity in early May. Chances are good that the spring peeper chorus is now happening earlier than in the past, according to a study by James Gibbs, from the State University of New York in Syracuse, and Alvin Breisch, of the New York Department of Environment Conservation.

From 1900 to 1912, Albert Wright, an instructor in zoology at Cornell University, visited ponds around the campus daily each spring to record the date of the first calls of frogs. Ninety years later, volunteers collected the same kind of information for the New York Amphibian and Reptile Atlas, allowing Gibbs and Breisch a chance to compare. Wright, on average, heard his first peepers on April 4. Atlas volunteers heard them around March 20, about 13 days earlier.

For us, it is spring music to our ears. For the peepers, it is a singing battle of life and death. I hope their spring tradition goes on and on.

Just a Teaspoon of Oil

Striped Skunk. /Brian Garrett

There is nothing like the fresh smell of an April morning … unless, during the night, a skunk skulked about your neighborhood. The striped skunk is armed with just a mere teaspoon of odoriferous oil in its two anal glands, but a little bit goes a long way.

Skunk oil research has been going on for over a century as scientists have tried to determine what makes the stuff so potent that it can drive a bear away. Way back in 1896, Thomas Aldridge at Johns Hopkins University showed that humans could detect the smell at just 10 parts per billion, the equivalent to detecting just one drop of it diluted into a medium-sized, backyard swimming pool. More recently, William Wood, a chemist from Humboldt State University, pointed out that a number of chemicals have been incorrectly attributed to skunk oil over the years, and his work has now given us a fairly complete understanding of the chemical compounds and how to neutralize them.

The scent-gland secretion is a yellow oil composed primarily of volatile compounds known as thiols, and their derivatives. (A thiol is a compound distinguished by its sulfur-hydrogen bond.) Most of us immediately recognize the smell of ethanethiol (also called ethyl mercaptan), a common thiol that’s added to otherwise odorless propane gas so we can easily smell any leaks. Another thiol creates the “skunky” smell of beer after it has been exposed to ultraviolet light. The thiol derivatives present in skunk oil are not particularly odoriferous, but they are easily converted to far more potent thiols when they react with water

Skunks are reluctant to use the oils though. With only enough for a half dozen sprays at most, and a 10-day period to manufacture more, skunks will only spray if they absolutely have to. In an attempt to avoid spraying, skunks often give warning. First, they show their striped white back to warn you. This is followed by threat behaviors, like stomping with both front feet, sometimes charging forward, and then edging backwards dragging their feet and hissing. If all this fails, watch out.

Each spray gland has a nipple, and skunks can aim and direct the spray using highly coordinated muscles. A skunk can spray up to 25 feet and hit something fairly accurately up to 7 feet away. When there is a target, they can direct a fine stream right at the victim’s face. When being chased, a skunk will instead emit a foul cloud for the predator to run into.

Watch a YouTube video, a bit out of focus but still neat, showing how they spray:

There is one predator that remains undeterred by the odiferous oil, the great-horned owl. The small size of the olfactory lobes in their brains suggests that they have a very poor sense of smell. Some individual owls can downright stink of skunk, a common complaint among wildlife rehabilitation workers. Their nests can even smell of their musky meals. But larger-lobed mammals quickly learn to avoid the white stripe in the night.

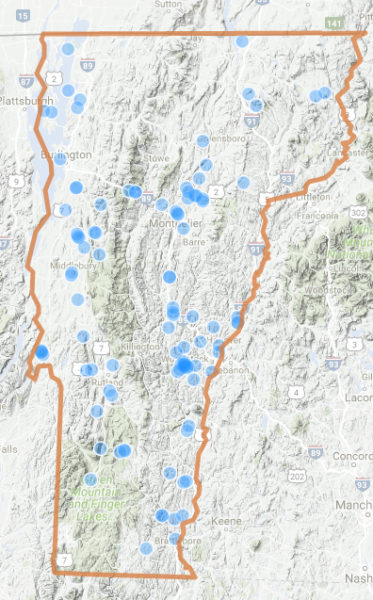

View a map and images of observations in Vermont and add your’s to iNaturalist Vermont.

Beautiful photos, and all so interesting!

Thank you for this informative and much-needed promise of Spring! It seems that this year’s temperatures are cooler than 2016. We’ve yet to hear peepers in the nearby vernal pools, but the phoebes arrived last week and have begun nesting. My motto: Hope springs “infernal”

Thank you for this lovely post. Your photos are spectacular. On Sun. May 7, 2017 I observed trout lilies in Norwich VT. Two years ago they were out in Quincy Bog, NH on April 22.