A Field Guide to January

Although the days are slowly growing longer, life in the Northeast now finds itself in the coldest depths of winter. January is about survival. Wildlife that doesn’t migrate adapts instead in order to make it to spring.

Black Bear Birth

By now bears are ensconced in their winter dens, slowly burning the thick layers of autumn fat. Later this month and into early February, the females will give birth. The newborns weigh about same as a can of soda. They’ll nurse on their mother’s high-fat milk and by spring they will have grown to be 6 to 8 pounds.

Deer in the Yard

White-tailed Deer survive the harsh northern winters using specific winter habitat, what most of us call “deeryards.” These areas have ample evergreen trees for cover on slopes that often have a southerly aspect, providing protection from deep snow, cold temperatures, and wind. Deeryards might be only a few acres to perhaps as large as 100 acres. If conditions remain the same, these yards can be used for generations. Deer may migrate from miles around in late fall to use these areas for the winter. The deer cut their metabolism in half during this time of scarcity in an effort to make it until the lush grasses of spring arrive.

Deeryards are also important for a variety of other wildlife: porcupines, snowshoe hare, fox, fisher, coyotes, bobcats, crows, ravens, crossbills, owls and more. Human encroachment or forestry operations can have a devastating effect on these stands and the wildlife that rely on them. Deeryards make up a small percentage of the land. Only 8% of the forested landscape of Vermont has been identified as deeryard.

The Eagles Have Landed

Bald Eagle populations have been slowly rising for decades in the Northeast. Winter provides a great opportunity to see these majestic birds as the congregate around areas of open water on lakes and rivers where food is likely to be found.

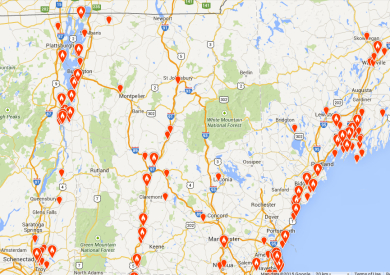

Well-known places in Vermont to see eagles include: below the Wilder Dam in Hartford or along the edge of ice on Lake Champlain, specifically near Chimney Point Bridge and Fort Cassin Point near Ferrisburgh. Your best source of recent sightings is on Vermont eBird. Check out the live map of Bald Eagle reports for the whole region and plan your trip.

Ruffed Grouse Are Down Under

Where’s the warmest place for a bird to spend the night? Depending on the temperature, it might be subnivean. WIth the air temperature dropping well below freezing, a deep blanket of snow might be the insulation that separates life from freezing death for a Ruffed Grouse. You can find places they’ve roosted by the marks in the snow showing where they entered and where they exited their winter den. They may even burst out of the snow in front of you, frightening you into a warmer state. On a warmer night or when snow conditions are poor, grouse may settle for roosting in the branches of an evergreen tree.

Each fall Ruffed Grouse grow comb-like rows of bristles (called pectinations) on their feet. These create a “snowshoe” effect for the grouse, allowing them to walk on the surface of the snow. Grouse also have extra feathers that cover the nostrils on the beak to make the air just slightly warmer as it enters their airways, like a balaclava mask you might wear on a cold winter day.

Love the eagle photo!