The avian breeding season is winding down. Even a few southbound shorebirds will trickle through the region this month on their “fall” migration. But as the dawn bird chorus now fades from northern woodlands, fields and wetlands erupt in the sparkle and drama of summer insects. Here’s a short guide to some of July’s lesser known natural history.

Watching JULY PERENNIALS

Four plants serve as a backdrop for four natural history events not to be missed here in the Northeast each July. So consider this your annual reminder to seek out drama among the plants:

European Skipper with pollinia stuck to its foot while nectaring milkweed. / © K.P. McFarland

The Milkweed Flower Trap

Although it is by no means a carnivorous plant, Common Milkweed can be a killing field for small insects. Take the saga of a European Skipper, a tiny orange butterfly now on the wing. With its foot stuck in a milkweed flower like a Chinese finger trap, the skipper was struggling to free itself. On another flower nearby only a leg remained from a previous struggle. Survey enough milkweed flowers and eventually you’ll find a few dead insects, usually small species, left dangling from a leg or two.

Here’s a full report from a field full of milkweed.

The Primrose Ruse

Like most of you. Bryan Pfeiffer likes to spend his summer leisure time contemplating the tongue of the Primrose Moth. Okay, it’s not exactly a tongue. Butterflies and moths have a straw-like proboscis that they coil like a watch spring and unfurl to suck nectar from flowers (and essential minerals from mud or scat). The Primrose Moth’s proboscis is about half the length of its body. That anatomy alone might be enough to generate interest in this insect. But now consider that the Primrose Moth is Pepto-Bismol pink with a lemony margin at the tips of its wings. In that pink presentation and probing proboscis, the Primrose Moth offers us a lesson in form, function and evolution.

Read more on Bryan’s blog.

Waterlily Borer Moth. / © K.P. McFarland

Water Lilies: A Floating Microcosm

At the height of summer many ponds are covered in lily pads with beautiful white or yellow flowers spread across the surface. Moose munch on them. Beaver and muskrat devour them. Deer consider them delicious. But peer a little closer and you’ll find an amazing miniature world inhabiting each floating leaf. Even moths find a home on water lilies. The caterpillars of the water lily borer moth feed on leaves and tunnel into the stalks of the lily pads. Here’s a report from the ponds.

The Most Elegant Plant in the Woods

In the company of a Cape May Warbler, you might not notice the diminutive bloom at your feet. As you search for Moose, you might very well step upon this unassuming wisp of green and pink. Yet in the struggle for stature, this tiny plant might find no greater sponsor than biologist Carl Linnaeus. The father of modern taxonomy had a fondness for Twinflower. But it shouldn’t take the guy who brought order to nature to bring you to this elegant plant. Head for damp evergreen woods this summer. And when you find it, Twinflower will bring you to your knees. Bryan reports on his blog.

Making more Monarchs

A Monarch caterpillar notches a milkweed leaf to help slow the flow of sap before feeding. An unhatched egg is stuck to the underside of the leaf near the end of the caterpillar. / © K.P. McFarland

Monarchs are famous for their amazing fall migration, flying thousands of miles from the northern U.S. and Canada, south to winter in the mountains in central Mexico each year. July is a time when the last generation of Monarchs, those that will ultimately migrate, is being produced, perhaps in a milkweed patch near you.

Arriving as early as mid May in some years in the Northeast, Monarchs probably have two generations here during the summer before migrating southward each fall. Some years, its impossible to find caterpillars of the second generation in July and August, while in other years (last year was above average), they seem to be plentiful. I have noticed that in late July and August, the place to find hungry caterpillars is on younger and more succulent milkweed. And in late summer, the only places you find this are areas that were mowed in early July.

Research in New York found that manipulating Common Milkweed phenology through mowing could be used to increase monarch productivity in late July and August. Biologists mowed strips in fields at the beginning of July, late July, and mid-August. They compared these to unmowed control areas by carefully monitoring milkweed growth and counting Monarch eggs and caterpillars. As they predicted, the mowing of fields with Common Milkweed extended the monarchs’ breeding season and increased overall monarch reproduction.

The authors wrote, “We found mowing on July 1 and 24 spurred the regrowth of milkweed and sustained a more continuously suitable habitat for monarch oviposition and larval development than the control. Mowing on August 17 proved too late for recovery of the milkweeds. Significantly more eggs were laid on the fresh resprouted milkweeds than on the older and taller control plants. In the strips mowed on July 1, peak egg densities occurred in late July; in the strips mowed in late July, peak egg densities occurred in early to mid August.” But it is important to remember that if you mow for Monarchs, only mow patches or some strips so that older growth and other flowering plants will be available for adults and other pollinators.

Adult Monarchs need sources of nectar to nourish them throughout the entire growing season and during migration. Try to include a variety of native flowering species with different bloom times to provide Monarchs with the food they need to reproduce in the spring and summer and to migrate in the fall. Offering a wide array of native nectar plants will attract not only Monarchs but other butterflies and pollinators to your habitat all season long. You can get a list of Monarch nectar plants for your region from Xerces Society’s Monarch Nectar Guides.

The 2018 International Monarch Monitoring Blitz July 28 – August 5

In the last two decades, the eastern Monarch population has declined by 80%. We still have a lot to learn about Monarchs in order to protect them efficiently, and you can help by taking part. From July 28 to August 5, butterfly watchers across North America are invited to take part in the International Monarch Monitoring Blitz to help provide a valuable snapshot of Monarch population status across their late summer range. Participation is simple: find a milkweed patch and look for Monarchs, counting the number of stems you examined as well as the number of eggs, caterpillars, pupae, and adults. Then, share your observations with Mission Monarch. Visit Mission Monarch to learn more.

Getting Diagnostic with Darners

The borken (interrupted) thorax stripes on this darner reveal it to be a Variable Darner (Aeshna interrupta). / © Bryan Pfeiffer

They are the big, showy dragonflies of summer — cruising wetlands, beaver ponds and backyard ponds with all the audacity of an ancient predator. Darners flash their pastel blues, greens and yellows from now through fall. Vermont has no fewer than 10 species of these “mosaic darners” in the genus Aeshna, some quite rare and others fairly cosmopolitan.

But we can always learn more about the distribution of these darners. And for the wonderful citizen naturalists who contribute their sightings to the Vermont Atlas of Life Damselfly and Dragonfly Atlas (through our iNaturalist portal or on Odonata Central), the best way to identify a mosaic darner is with a lateral image of the thorax. The profile is what counts. Every darner can be identified this way, and not always with a dorsal photograph. So please try to “shoot” your darners from the side. The photo-observation curators at the Vermont Atlas of Life will be grateful.

And, don’t forget to get your copy of our new Vermont Damselfly and Dragonfly Field Checklist. This field card includes Odonata species compiled by the Vermont Damselfly and Dragonfly Survey. Use it in the field to keep track of your sightings. Download the card (PDF) and print the two-page document front-to-back.

Little Loons on a Lake Near You

Male and female Common Loons both tend to their young, feeding insects and minnows at first and larger fish later. Although loons will eat almost any fish they catch, perch are a favorite food. A loon’s average dive length is 35-40 seconds. Most fish are swallowed underwater with only the occasional larger fish brought to the surface. In a loon’s gizzard, which contains small stones, powerful enzymes and stomach acids help to digest the fish – bones included.

Adults guard their chicks during this period. Males might “yodel” at intruder loons or boaters who come too close. If intruder loons are present, chicks are often hidden near shore. The parents will also move the family to areas with less wind and wave action.

Common Loons will also eat live bait and lures from anglers. We routinely encounter loons tangled in fishing line, and loons that have ingested fishing line and bait. The results can often be fatal. Please “reel in” when loons are diving nearby and avoid using lead fishing gear of any kind.

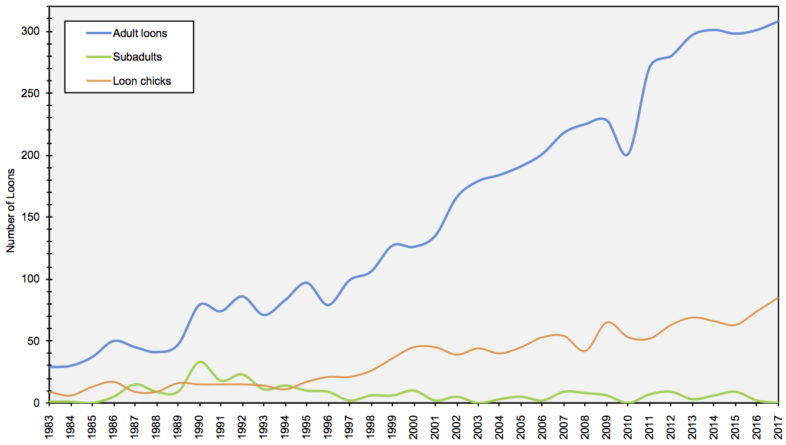

Join the 36th Annual Vermont LoonWatch on July 21

Survey a lake for one hour on the third Saturday of July each year. If you’ve got time, survey a few lakes. On this single day, we cover more than 130 lakes and ponds statewide each year. It’s the single most effective way for VCE to document and track breeding loons across the state. To get an assignment for the annual LoonWatch, contact our loon biologist, Eric Hanson. Eric keeps a list of lakes where we need volunteers.

Here’s a map of the latest Common Loon sightings in Vermont from Vermont eBird, a project of the Vermont Atlas of Life. If you see loons, please report them to Vermont eBird and help us track their populations.

NATIONAL MOTH WEEK – JULY 21-29

Black-and-yellow Lichen Moth (Lycomorpha pholus) sipping nectar from Buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis). / © K.P. McFarland

National Moth Week celebrates the beauty, life cycles, and habitats of moths. “Moth-ers” of all ages and abilities are encouraged to learn about, observe, and document moths in their backyards, parks, and neighborhoods. Held worldwide during the last full week of July, National Moth Week offers everyone, everywhere a unique opportunity to become a citizen scientist and contribute information about moths. Through partnerships with major online biological data depositories, participants can help map moth distribution and provide needed information on other life history aspects around the globe. Here at VCE, we map moth distribution throughout the year on iNaturalist Vermont, a project of the Vermont Atlas of Life.

National Moth Week celebrates the beauty, life cycles, and habitats of moths. “Moth-ers” of all ages and abilities are encouraged to learn about, observe, and document moths in their backyards, parks, and neighborhoods. Held worldwide during the last full week of July, National Moth Week offers everyone, everywhere a unique opportunity to become a citizen scientist and contribute information about moths. Through partnerships with major online biological data depositories, participants can help map moth distribution and provide needed information on other life history aspects around the globe. Here at VCE, we map moth distribution throughout the year on iNaturalist Vermont, a project of the Vermont Atlas of Life.

How many moth species can we find during moth week?

We encourage you to add your photographs of moths too. Thanks to the tireless efforts of both professional and amateur Lepidopterists, since the 1995 landmark publication Moths and Butterflies of Vermont: A Faunal Checklist, nearly 400 new moth species have been found in Vermont. Preliminary results show us that there are now over 2,200 species of moths known from Vermont. And, there are likely many more awaiting our discovery.

Since 2013, professional biologists and naturalists have contributed moth observations to the Vermont Atlas of Life through our iNaturalist Vermont. Many of us turn on special lights in our backyards on summer nights to find hundreds of moths and other insects gathering on our sheets, hunt fields and forest for day-flying moths, and place rotten fruit bait out to attract other moths. Many of these moths can be identified from good photographs (although some are impossible without dissection and examination under a microscope). With today’s amazing digital photography technology, coupled with the newer Peterson’s Field Guide to Northeastern Moths and web sites like iNaturalist Vermont, BugGuide, Moth Photographers Group, or Moths of Eastern North America Facebook Group, moth watching (aka mothing) has become increasingly popular.

Moth watchers have added a whopping 91 news species to the Vermont checklist via iNaturalist Vermont and have documented over 865 species across the state. What’s even more amazing is that we’ve recorded over 15,000 moth observations, which help to understand their phenology, habitat use and range in Vermont like never before.

Ash Trees Aren’t the Only Thing in Peril

There are over 8.7 billion ash trees growing in the lower 48 states, comprising 16 species, and they’re all susceptible to loss from the introduced Emerald Ash Borer. But there’s more at stake than just the trees. A recent survey has revealed that 100 species of ash-dependent specialist invertebrate herbivores are too.

Adult Emerald Ash Borer. Image from Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources – Forestry Archive

Emerald ash borer (EAB; Agrilus planipennis) is an exotic beetle that was discovered in southeast Michigan in 2002. The adult beetles nibble on ash foliage but cause little damage. The larvae feed on the inner bark of ash trees, disrupting the tree’s ability to transport water and nutrients, eventually killing it. Healthy ash trees can die within 1-4 years of showing their first sign of infection. EAB probably arrived in the United States in wood packing material from its native range in Asia. As of May, it is now found in 33 states and 3 Canadian provinces.

Adult Beetles are metallic green and about 1/2-inch long and leave a D-shaped exit hole in the bark when they emerge in spring. Woodpeckers like EAB larvae; heavy woodpecker damage on ash trees may be a sign of infestation.

A recent study by David Wagner at University of Connecticut and Katherine Todd from Ohio State found that 100 species in 5 insect orders and several mites would be imperiled or extirpated by the loss of ash trees. Thirty-nine of them belonged to just four groups: sphingid moths, plant bugs, bark beetles, and seed weevils. A third of the total species were moths (33 species), including 9 species of hawk moths (4 are known from Vermont and 6 are known from the Northeast), about 8.5% of resident North American hawkmoth species. Hawk moths are important pollinators and food for birds and mammals.

The biologists lamented that we were missing even basic information about host breadth, distributions, and life histories for even seemingly well-known species and argued that targeted surveys of all 16 species of ash trees were needed. Meanwhile, you can report all of your ash tree observations and the insects on them to iNaturalist Vermont, and keep your eye out for signs of Emerald Ash Borer.

iNaturalist Vermont Observations

- Map of Ash tree observations

- Ash-dependent sphinx moths in Vermont:

will be visiting southern Vermont (Woodstock and Stowe) in September/October – where would the best places be to see the migrating Monarch butterflies. Normally we are in Cape May NJ this time of year, but this year we will be in Vermont and CT – any suggestions? thank you.