A Field Guide to October 2017

October is a month of change. The leaves slip from green to gold. Then, suddenly, they all seem to drift to the ground. The trees are nearly naked once again, and ‘stick season’ has arrived. So, here’s your field guide to some moments that you might not otherwise notice during these few precious weeks that feature colored hills beneath a deep blue sky with the last Monarchs fluttering southward.

A Fall Flowering Tree and Cold tolerant moths

The yellow streaming blooms of Witchhazel (Hamamelis virginiana) can be found in the understory in October. The long, bright-yellow petals, sweet smell of nectar with pollen loaded stamens near the source, suggest that insects are the mode of pollination. UVM biologist and naturalist Bernd Heinrich discovered that Owlet moths feed at the flowers on late evenings in October and likely are the main pollinators. These moths need sugars from sap or nectar to maintain high temperatures for flight on cool nights. Add your observations to iNaturalist Vermont and help us track Witchhazel flower phenology.

Going Deep

In the spring Spotted and Jefferson’s salamanders crawl to vernal pools — temporary woodland ponds that fill with water but then dry out later in the summer, providing a fishless environment for larval salamanders, where they mate and lay eggs. But for 90% of the year these salamanders are elsewhere in the forest. Sometimes you can find them by flipping over a large stone or rolling a rotting log, but for the most part, they are tough to find.

Technology allowed VCE biologist Steve Faccio to easily spy on a salamander using miniature tags that emit a radio signal. With a radio receiver and small antenna, Steve could then monitor the salamander’s movements and locations.

Standing on a forest path near the site, Steve turned on the radio receiver and tuned to a salamander’s frequency. A faint, but audible “ping” sounded from the headphones. A few minutes later Steve was in the general area of the animal. The signal was strong, but he couldn’t quite pinpoint it. The salamander was underground.

After an hour on hands and knees, Steve found the exact spot. A series of narrow, branching tunnels under the leaf litter and rotting logs held the prize. Steve was able to move just a few leaves and there it was peering out from a tunnel opening.

These salamanders can’t dig. They use shrew, mice and chipmunk tunnels for refuge. In fact, the tunnels are so important to them that Steve could predict areas in the forest that would be used by the salamanders just by the density of mammal tunnels. Without small mammals, there were no salamanders to be found.

After tracking them to these surface tunnels all summer long, suddenly, with the chill of fall, the salamanders changed behavior. They entered more vertical tunnels that led deeper underground. By November nearly all of them were deep under the earth. The radio signal only traveled about two or three feet, so eventually the signals were lost. They had gone deep enough to escape the ground penetrating frost and spying by radio from above.

The Last of the Warblers

While most other warblers have moved southward already, Myrtle Warblers (AKA Yellow-rumped Warblers) pass through Vermont in high numbers in October. Myrtles are the only warbler able to digest the waxes found in bayberries and wax myrtle bushes along the coast, allowing them to winter farther north than other warblers, sometimes as far north as Newfoundland. They are a versatile forager – sallying from a tree after flying insects, picking at spider webs, skimming insects from water surface or a pile of seaweed, gleaning from leaves and bark, and if all else fails they feed on berries. Listen for their distinctive chip note and watch them feeding in the morning sun.

Long Live the Queen!

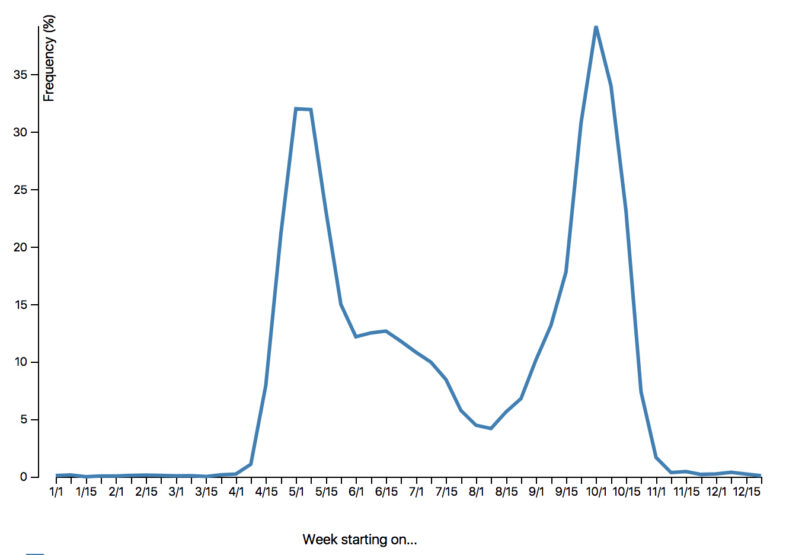

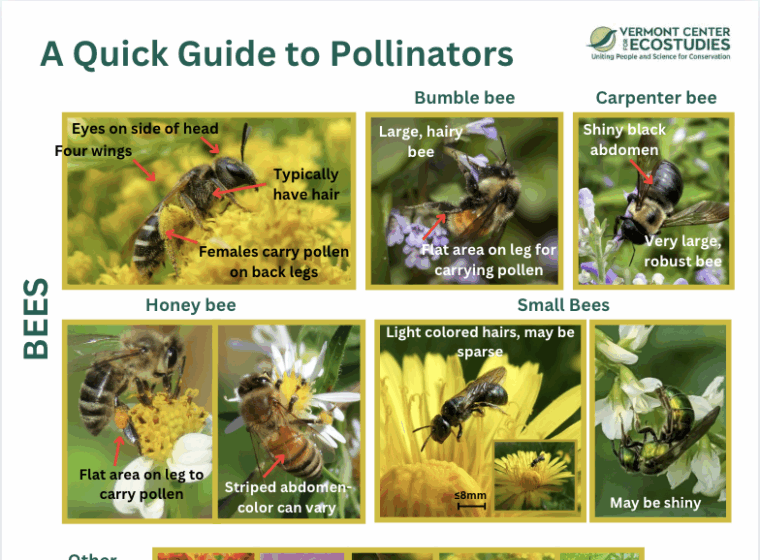

Most of the bumblebees you see flying right now are males (drones) looking for a mate or young queens preparing for winter. Each year in the bumblebee kingdom, only a queen will carry the colony’s torch through winter to produce the next generation. Every other bee – workers, drones, and the old queen – dies with the onset of fall frost.

Not so with the honeybee, with which more people are familiar. In the dead of winter, visit the honeybee observation hive at the Montshire Museum of Science, which is made with a pane of glass on each side of a thin box. The workers are all gathered around the queen in one spot. If you put your hand on the glass away from them, the glass is frigid, but the back of your hand on the glass right in the center of the cluster is incredibly warm. Eating stored honey keeps their metabolisms high enough to produce excess heat and keep the cluster alive.

Bumblebees take a completely different approach. They do not put all of their energy into food storage for the winter but hedge their bet on the survival of a few queens. During the waning days of late summer and early fall, larvae begin to develop into virgin queens and males rather than the workers that have been hatching all summer. Colonies may produce up to one hundred reproductive bumblebees, hoping that at least one or two queens will survive to re-establish a colony the next spring.

When male bumblebees emerge from the cocoon, they may spend several days in the hive and drink some of the stored honey. (Bumblebees do produce some honey, just not the great quantities of their honeybee brethren.) Then the males leave the nest to forage and live on their own, often finding shelter under plant leaves and flowers during inclement weather and at night. I have seen them in the cool morning air sitting on goldenrod flower heads barely able to move. The male bumblebees have one charge in life: stay alive long enough to mate. Each male leaves a chemical attractant along a regular flight path in its territory.

New queens emerge from the hive a week after the males. Unlike the males, they will leave the nest to forage by day and return for shelter at night. And unlike their sisters, the workers, they do not add any provisions to the nest.

As the days grow shorter, a fertilized queen visits flower after flower, drinking lots of nectar to build body fat and fill her honey stomach. The honey stomach is a small sack that can hold between five-hundredths and two-tenths of a milliliter (A teaspoon holds about five milliliters). Each flower may yield only one thousandth of a milliliter of nectar, causing the queen to visit up to 200 flowers to get her fill.

Not all flowers are alike. Fall flowers like goldenrod and aster, for example, generally yield far less food than jewelweed blossoms. Bumblebees must sustain thoracic temperature at 86 to 95 degrees F. to be able to fly. So when the morning temperatures are cool, it does not pay for them to visit flowers of poor quality, because they burn as much fuel as they gain from foraging. Queens won’t emerge to forage in the cool mornings until the air temperature is around 50 degrees.

While the young queens are buzzing around foraging, they are also picking up any perfume left by a male. If the scent is to their liking, they may land and wait for the male. Mating can last up to an hour and a half, but sperm transfer generally occurs in the first two minutes. Why the long encounter? Males want to make sure the future colony belongs to them. When he is done mating he exudes a gummy substance onto the queen that blocks any other males from mating with her.

When the queen has mated, she searches for a good place to burrow into the soil for the long winter wait. Once under ground, usually one to six inches down, the queen somehow knows to avoid the false start of the January thaw and wait until late April or early May, when the warmth of the spring sun penetrates her underground home and she emerges to forage and start a new colony. The queen lives!

Many people live in fear of bumblebees, perhaps because, unlike us, they don’t try to keep their whole clan alive for the winter, instead rolling the dice on the survival of just a single individual. That, and the fact that bumblebees sting us. But think twice before swatting a bumblebee at this time of year, especially one that’s not bothering you. You’ll never know if that might have been the one

The Phenology of Fall Leaves

We’ve all learned the basics of how and why leaves change color in the fall. But on this edition of Outdoor Radio, we take a deeper look at the chemistry of fall foliage and take leaf peeping to a whole new level. We meet Joshua Halman, a Forest Health Specialist with the Vermont Department of Forest, Parks and Recreation at Underhill State Park, where a fresh autumn snow has fallen overnight. The department has monitored these trees for 25 years, recording color change and leaf drop here and at other places around the state.

Halman reports that this work has documented the impacts of climate change. “Seen over this time, the peak color and the main time for leaf drop has actually become later,” Halman explains. “What we’re seeing since we started recording our fall phenology data is that, on average, foliage is peaking about eight days later over that 25-year period.”

Listen to the show

You can find more information at the Vermont Department of Forest, Parks and Recreation’s Forest Health Monitoring page, and learn more about fall leaves on the VCE blog – Turn Red or You’re Dead and Abscission and Marcescence in the Woods.

The idea that foliage peak has moved 8 days in 25 years is very concerning at best and frightening perhaps when you think of all the other biological systems that could become out of balance. Do you have any other comparison data that would go back even further in years? I am thinking of the onset of maple sugaring as recorded by sugar makers or the ice-out dates for various lakes as recorded by contests to guess the closest date and time, etc.