A Field Guide to September

It can happen almost anywhere. On a cool, foggy morning, for example, when fall warblers drop from their nocturnal migratory flights into your backyard. Or along a big river some evening when you notice a Common Nighthawk moving south — then another, and another. Or on some summit when the Broad-winged Hawks kettling above convince you that summer is indeed over. Here is your field guide to life slowing down and on the move in September.

Hawkwatching Confidential

If it’s September, it’s a broadwing up in the sky. Okay, that’s a generalization, but not a bad one. So if those migrating hawks appear to you to be little more than specks in the sky, or if you need to brush up on your hawkwatching skills, VCE research associate Bryan Pfeiffer offers some advice on his blog. And if you ever wanted to know what it was like to go on a hawkwatch, join Outdoor Radio on the expedition to the Putney Mountain hawkwatch.

Ghosts on the Radar

The circles around the weather radar are likely birds migrating after dusk. Note the hurricane making landfall at the same time in Florida.

When radar was first deployed, operators called them “ghosts”, mysterious echoes seen on radar screens on clear nights. Some of these were caused by migrating birds and insects. Since the first units were placed along the Gulf Coast in the 1950s, ornithologists and birders have become increasingly aware of the power of using radar as a tool for understanding bird migration. In addition to detecting and depicting meteorological phenomena, this radar network can be used to watch and to track the movements of birds. And, its available at your fingertips. When a cold front passes through and the winds are from the northwest, visit the NOAA weather radar site on the internet when it becomes dark outside and see if the birds have lifted off and are headed southward. Learn more about radar ornithology from the eBird blog.

Nighthawk Watching

Common Nighthawk in flight. Photo Bryce Bradford – https://www.flickr.com/photos/brb_photography/

On warm summer evenings in the breeding season in Vermont, Common Nighthawks once roamed the skies over treetops, and towns. Their sharp, electric peent call was the first clue that they were overhead. At dusk, these long-winged birds flew in graceful loops, flashing white patches out past the bend of each wing as they chase insects. Those days are mostly gone now, but in August during migration, the careful observer can still witness their spectacular flight here in Vermont as they whirl southward on their autumn migration.

Although most often seen migrating at dusk here in Vermont, Common Nighthawks migrate at all hours of the day, often in large flocks, on one of the longest migration routes of any North American landbird. Many travel overland through Mexico and southward through Central America, while others pass through Florida and across to Cuba southward, flying over the water to reach their wintering grounds in South America thousands of miles away. Read more on the VCE blog.

What are those Red Bugs?

Adult and nymph Boxelder bugs gathering on a warm barn wall under a box elder tree. © K.P. McFarland

Starting in mid‑July, Boxelder Bugs (Boisea trivittata) are in seed-bearing (female) Boxelder Trees where they lay eggs on trunks, branches, and leaves. They feed on the seeds on the ground in the spring. During late summer and fall, they start to leave the trees where they were feeding in search of a spot to overwinter. You may see them massed together on warm, exterior walls, rocks and tree trunks. Although you can find nymphs during fall, only fully grown adults survive the winter. They are most abundant during hot, dry summers that are followed by warm springs. As the weather cools, they find cracks and spaces around homes, outbuildings, rocks, and trees. In some cases they end up inside buildings, where they are often found around windows.

Radiant Red

Bright red leaves under a clear blue sky are spectacular to see. But what is beauty to us may be survival to a tree. As the green chlorophyll in leaves breaks down without replacement, we begin to see the underlying orange carotenoids and yellow xanthophylls. These pigments help capture light energy during the growing season. But unlike yellow and orange pigments, red anthocyanins are made during fall leaf senescence. They are manufactured from sugars found in the leaf, produced in greater amounts during cooler nights and sunny days. When a hard freeze comes along, production ends. Why would a tree use energy to make a pigment in a leaf that is about to die and fall off? Find the answer on the VCE blog.

The Last Flower

Yellow and spindly, it is the lonely flower of autumn. Even after the leaves have fallen and the Monarchs have left us for Mexico, Witch Hazel is acting like it’s spring outside. In barren woods this shrubby tree attracts some of the year’s final pollinators — the late-season flies and moths that have few other options for nectar. And once pollinated, the flowers take a full year or more to mature into seed-bearing capsules. That’s when the fun begins. In the fall, Witch Hazel ejects its seeds in a subtle woodland fusillade. Or, as David Taft writes in The New York Times: “The clattering seeds and popping pods fill the woods with vibrancy.”

Humming Along

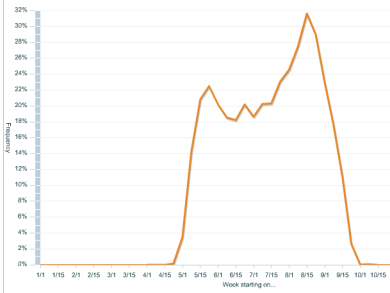

Frequency of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds reported on Vermont eBird checklists.

When the flowers stop blooming and insects stop flying, Ruby-throated Hummingbirds have gone south. Some adult males start migrating south as early as mid-July, but the peak of southward migration is August and early September, and by October they’re all gone.

Most, if not all, of the hummingbirds at your feeders in September are migrants and not the same individuals you’ve watched all summer. Since they all look alike, it’s difficult to know for sure, but banding studies have shown the turnover. It’s not necessary to take down feeders to force hummingbirds to leave, and in the fall all the birds at your feeder are already migrating anyway. Keep them up as long as you can and just maybe a wayward rare species will find them.

Where do they all go? There is some evidence that more of them travel around the Gulf of Mexico in fall migration, rather than cross it as they do in spring. They’ll spend the winter in Mexico and Central America. Weighing a mere two-tenths of an ounce, they’ll make the round trip back in April and delight us once again with their bright colors and active flights after our long white winter.

Flying Dragons

Dragonfly migration has been observed on every continent except Antarctica, with some species performing spectacular long-distance mass movements. Like birds, millions of Common Green Darners migrate to the north in the spring and south in the fall. Watch closely and you’ll see them passing overhead, often when the hawks are also on the move. They both use the passage of cold fronts to more easily glide southward. Where are they coming from and where do they go?

Our scientists are hot on the trail of discovery. They’ve teamed up with the Migratory Dragonfly Partnership, a group of biologists from across the continent, to better understand dragonfly migration. VCE, along with the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, is leading a groundbreaking study using trace elements found in dragonfly wings to trace spring migrants back to their natal origins. Learn more about this in a blog by Bryan Pfeiffer.

For the last week (it’s now 9/14) I have noticed the absence of songbirds in the morning and hummingbirds throughout the day. Only the squawking of jays and crows. It feels abrupt this year, or perhaps I’m more attuned to it than in the past. For reference, I’m at 1400′ elevation in Stowe, VT

Well, in September the birds are really on the move. So the fauna in any given spot can really change from even one day to the next depending on the arrival and departure of birds as they work southward with cold fronts. So I think this is fairly typical. It definitely happens in my yard for sure. Some mornings it can be hopping with activity and then a cold front comes and they take off with the night and migrate south. The next morning, silence and no activity.