Counting Birds: When Zeros Equal One or More

A volunteer conducting a Mountain Birdwatch survey. © Wendy Cole

We’ve all been there. A friend visits from out of town, and you take them birding at a reliable spot for your locally uncommon bird—say, Yellow-bellied Flycatcher. After hours of listening and walking around the woods, your search turns up empty. “I don’t get it,” you apologetically exclaim to your friend, “they are usually here—I just saw one yesterday.”

What this birder experienced is something that we population ecologists deal with on a frequent basis with count data—false zeros. False zeros occur in count data when an observer (often through no fault of their own) fails to detect an individual that is actually present. It’s easy to see how that could happen with owl species, for example—if they’re not calling then you’re unlikely to see one in the dark. It can be difficult to separate false zeros from real zeros (a zero count when a species is truly absent from a site), but projects like Mountain Birdwatch are designed to separate false and real zeros during the analysis.

So what kinds of processes affect the detection process during a Mountain Birdwatch survey? Clearly high winds and rain make it difficult to detect birds, and individual observers obviously differ in their ability to detect birds as well. One of the best documented sources of variation in the detection process, however, is the time of day that the point count or survey is conducted. Most birds’ singing rates and activity levels drop off throughout the morning, which makes them harder to detect as the morning progresses.

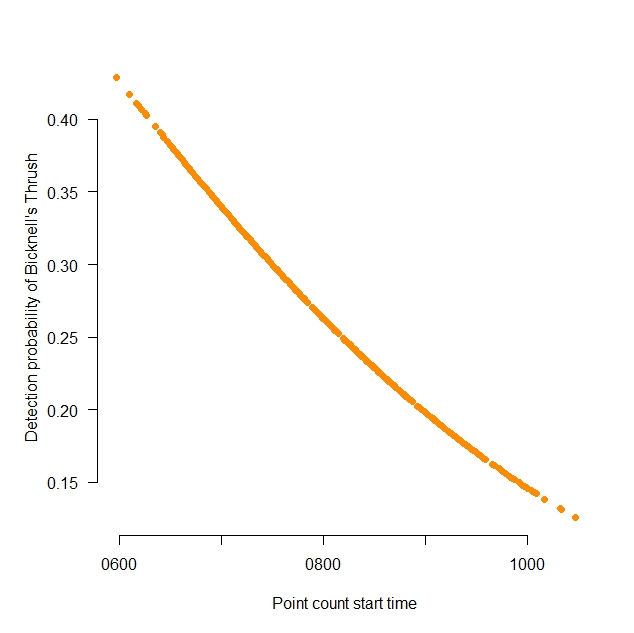

When is the best time to detect a Bicknell’s Thrush? At 6 am or earlier. The probability of detecting a Bicknell’s Thrush declines steady throughout the morning on Mountain Birdwatch routes.

Take a look at the figure showing detection probability of Bicknell’s Thrush calculated from Mountain Birdwatch data. An observer (with average birding ability) at a typical montane forest site has a 45% chance of detecting a Bicknell’s Thrush during a 5-minute point count at 6 am. Detection probability for that same birder, however, drops to 20% by 9 am. That means at 9 am that observer is failing to detect 80% of the thrushes that are present. Only conducting surveys at sunrise is impractical (think how many observers that would take), but we can statistically account for these missing birds during our analysis, and have a better understanding of bird population trends.