Field Guide to January 2019

Although the days are slowly growing longer, life in the Northeast now finds itself in the coldest depths of winter. January is about survival. Wildlife that doesn’t migrate adapts instead in order to make it to spring. Here’s a few tidbits of natural history happening outdoors this month around you.

It Takes Guts to Survive a Boreal Winter

Spruce Grouse eat low fiber foods in summer, mostly fruit and insects. But in winter, they switch to a diet of very high fiber when they eat mostly conifer needles. They forage at mid-crown level, perhaps because these needles are more palatable or higher quality; the branches are larger and also provide sturdy support; and they can see approaching predators while remaining better concealed in thicker foliage.

Back in the 1960s, biologists B. A. Pendergast and D. A. Boag wondered if this seasonal change in diet was accompanied by structural changes in the Spruce Grouse digestive system. For an entire year they sampled grouse each month in Alberta, Canada to find out. In their 1973 paper, they reported that Spruce Grouse gastrointestinal organs did change with seasonal shifts in diet.

In winter, when the birds ate more and poorer quality food to maintain their mass and energy balance, the gizzard grew by about 75%, and other sections of the digestive tract increased in length by about 40%. Captive birds from the same population that were maintained mostly on poultry feed did not have the same size or degree of seasonal gastrointestinal tract change. It takes guts to survive the long, dark winters in the boreal forest.

Ruffed Grouse Winter Adaptations

Closeup of a Ruffed Grouse foot showing pectinations. This one was killed by a Cooper’s Hawk. / © Sue Elliott

Each fall Ruffed Grouse grow pectinations, comb-like rows of bristles, on their feet. These create a “snowshoe” effect for the grouse, allowing them to walk on the surface of the snow. Grouse also have extra feathers that cover the nostrils on the beak to make the air just slightly warmer as it enters their airways, like a balaclava mask you might wear on a cold winter day.

Winter Finch Forecast

Ron Pittaway’s favorite finch is the Pine Grosbeak. And if you’re a birdwatcher in the Northeast, his winter finch forecast each September is likely your favorite annual report. Will it be a long finchless winter, or will be be dazzled with life and color? This year, Ron predicted an eastern irruption.

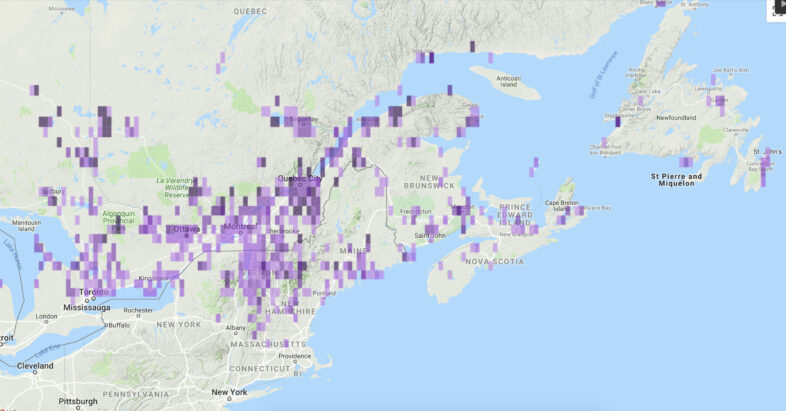

November passed into December and winter finch sightings were sparse, but suddenly reports began to dot the Vermont eBird map. The prediction held true. Pine Grosbeaks were being spotted feeding on crab apples and small flocks of Common Redpolls were found in weedy fields and backyard feeders.

Pine Grosbeak reports to Vermont eBird during December and January. Click on the map to see a live version and explore.

How does Ron make his predictions? In 2016 Ron told the Ontario Field Ornithologists News that, “Finch forecasting is an example of citizen science. I get tree seed crop information from staff of the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, and contacts from across Canada, New York State, New Hampshire and Alaska. I send out an email survey in mid-August asking contacts to rate tree crops as poor, fair, good, excellent or bumper. The list of trees includes spruces, pines, balsam fir, hemlock, birches and mountain-ashes. I also ask contacts if they are seeing finches. Then I map out tree seed crops and do a first draft in late August, updating it as reports come in. Normally I’ve heard from most sources by mid-September and post the forecast about the third week of September.”

Irruptions of winter finches southward are all about food. As Ron reported in September, “Cone and birch seed crops are poor to low in most of Ontario and the Northeast, with a few exceptions such as Newfoundland which has an excellent spruce crop. Expect flights of winter finches into southern Ontario, southern Quebec, Maritime Provinces, New York and New England States, with some finches going farther south into the United States.”

From grosbeaks to goldfinches, crossbills to siskins, and even purple finches; learn more in Ron’s article about this winter visitors. And join us on our Outdoor Radio adventure as we try to chase down a flock of Pine Grosbeaks last month in Montpelier Vermont.

Be sure to add all of your sightings to Vermont eBird, a project of the Vermont Atlas of Life.

Deer Yards: Key to Winter Survival

White-tailed Deer survive the harsh northern winters using specific winter habitat, what most of us call “deeryards.” These areas have ample evergreen trees for cover on slopes that often have a southerly aspect, providing protection from deep snow, cold temperatures, and wind. Deeryards might be only a few acres to perhaps as large as 100 acres. If conditions remain the same, these yards can be used for generations. Deer may migrate from miles around in late fall to use these areas for the winter. The deer cut their metabolism in half during this time of scarcity in an effort to make it until the lush grasses of spring arrive.

Deeryards are also important for a variety of other wildlife: porcupines, snowshoe hare, fox, fisher, coyotes, bobcats, crows, ravens, crossbills, owls and more. Human encroachment or forestry operations can have a devastating effect on these stands and the wildlife that rely on them. Deeryards make up a small percentage of the land. Only 8% of the forested landscape of Vermont has been identified as deeryard.

Listen to Outdoor Radio as they visit a deeryard and talk more about these important habitats.

Black Bear Birth

By now bears are ensconced in their winter dens, slowly burning the thick layers of autumn fat. January’s full moon is sometimes called the ‘bear moon’. Later this month and into early February, the females will give birth.The mother bear will lick them clean, keep them warm, and move into a position that makes it easier for them to nurse. The newborn cubs weigh about same as a can of soda. They’ll nurse on their mother’s high-fat milk and by spring they will be 6 to 8 pounds

“Who” Lays The First Eggs?

Listen for Great Horned Owls advertising their territories with deep, soft hoots in a stuttering rhythm: hoo-h’HOO-hoo-hoo. It can carry a mile or more. Both sexes hoot, with the female call higher pitched and consisting of 7 or 8 syllables. Even though the female Great Horned Owl is bigger, the male has a larger voice box and a deeper voice. Pairs often call together, with audible differences in pitch.

Great Horned Owls are one of the earliest species to nest in the Northeast, and are often brooding eggs as early as January. For nesting sites they use old hawk, eagle, heron or osprey nests, squirrel nests, tree hollows, or cliffs. Check out the Vermont eBird map to see all the sightings reported in January. From the first to the second Vermont Breeding Bird Atlas, Great Horned Owls decreased by 33% (57 to 38 blocks) with the greatest decrease in Taconic Mountains.

If you hear an agitated group of cawing American Crows, they may be mobbing a Great Horned Owl. Crows may gather from near and far and harass the owl for hours. The crows have good reason, because the Great Horned Owl is their most dangerous predator.

Great Horned Owls are covered in extremely soft feathers that insulate them against the cold winter weather and help them fly very quietly in pursuit of prey. Their short, wide wings allow them to maneuver in the forest while hunting prey.

Nice article and photos.

Great info! Thanks!! Shared with others.