Fir Mast and Winter Weather Drives Survival in a Montane Forest Bird Species

This is what I love about science. Our data picked up our hypotheses, laughed at us, and threw them back in our faces—we were completely wrong! That just shows you how much we still have to learn about the population ecology of birds.

I’m referring to a new VCE publication in the journal Avian Conservation and Ecology that documents unexpected results in our quest to understand how environmental processes shape the population dynamics of Bicknell’s Thrush throughout their annual cycle. While severe episodic weather (think hurricanes and blizzards) can directly kill adult birds (but rarely), the effects of weather on adult survival are largely moderated through changes in food availability and foraging opportunities that operate subtly throughout the year.

We know that not all of the birds that migrate from Vermont in autumn will return the following spring. For the vast majority of these missing birds, we will never know their fate… but that shouldn’t stop us from trying to figure out what’s really going on. So, the VCE team pulled out 15 years of Chris Rimmer’s Mt. Mansfield banding data (stretching back to 2001) to test a series of hypotheses about factors that limit apparent survival in 178 adult Bicknell’s Thrush.

We used the banding data to note which thrushes returned each year, and then applied Cormack-Jolly-Seber mark-recapture apparent survival models to tease out associations between those patterns and a suite of presumably important factors from the species’ annual cycle. We say apparent survival, because these models jointly contain the probability of an animal surviving from one year to the next (true survival) and returning to the same site (site fidelity). It’s often quite difficult to definitively determine if a bird died or emigrated to another mountain. Some of the explanatory factors in our models included the abundance of red squirrels (a common nest predator in some years), and weather effects (e.g., precipitation and the El Niño-Southern Oscillation [ENSO]) on food abundance on the breeding and wintering grounds. We found that Bicknell’s Thrush were more likely to survive from one year to the next, and return to Mt. Mansfield, when conditions were relatively wet on the wintering grounds in Hispaniola. These relatively wet December-through-March periods are actually the driest periods of the year for Hispaniola. In relatively dry years, it’s likely that fewer fruits and arthropods are available for consumption by Bicknell’s Thrush. Less food during this stressful dry period likely means increased chances of starvation and depredation, because birds must spend more time foraging and less time vigilantly on the look out for predators.

However, the largest effect on apparent survival patterns in Bicknell’s Thrush was directly related to balsam fir cone production on their breeding grounds. Fir cones are an important food source for red squirrels, and they store these cones in piles (called middens) over the winter to help them survive at high elevations. When few cones are available, the squirrels remain at lower elevations over the winter and the following summer. If the squirrels are absent from the spruce-fir habitat during summer, then Bicknell’s Thrush nests are much more likely to succeed due to lower depredation from red squirrels.

Considering this relationship between squirrels and nest success, we hypothesized that mature fir cones on the trees in autumn (before the thrushes migrate south) would serve as a warning to adult birds: Come back to this spot next summer, and there will be lots of squirrels who will eat your young. Similarly, we expected relatively high site fidelity of thrushes in years without cones in the autumn. But apparently the birds know more than we do, because we got it backwards!

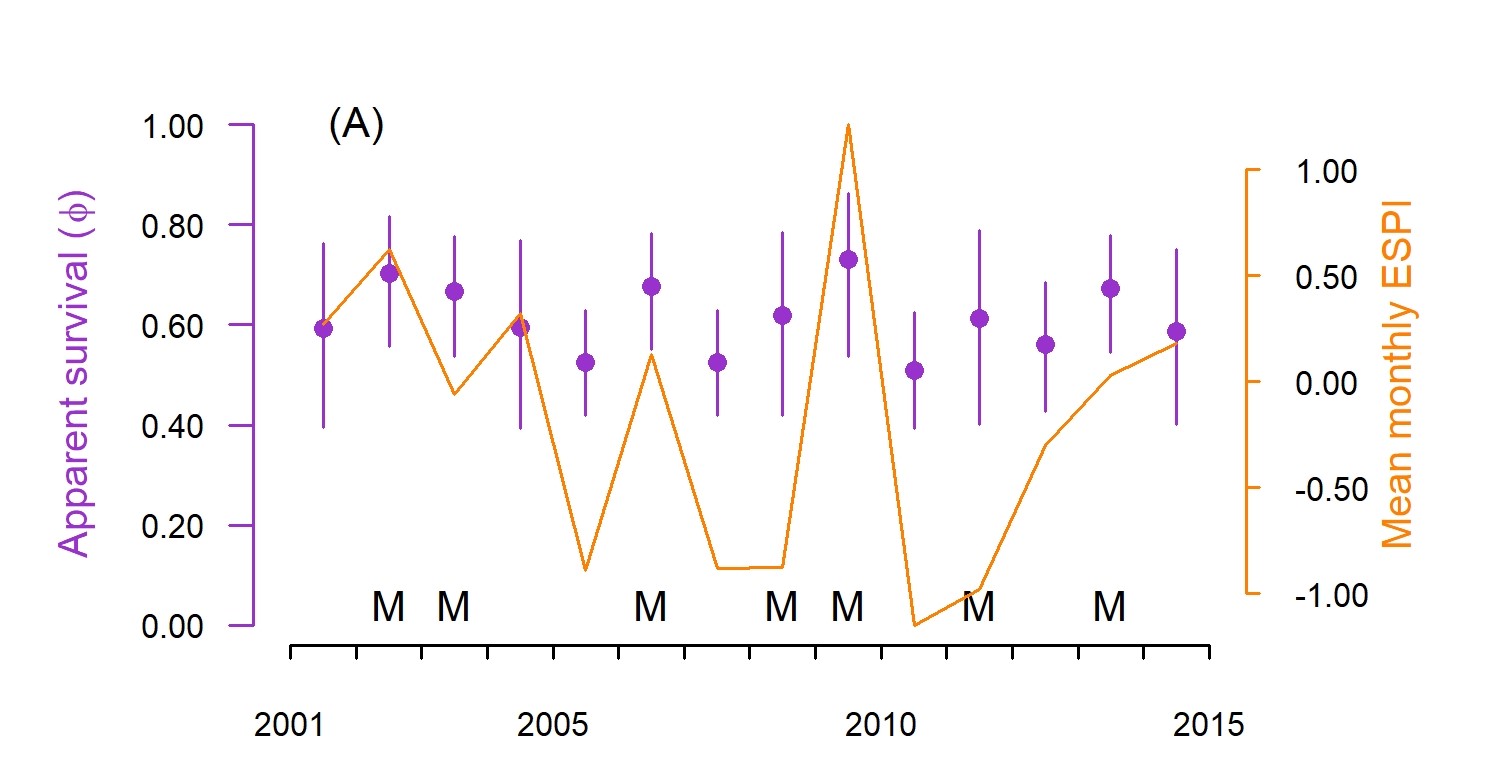

The purple line represents the annual apparent survival (with 95% confidence intervals in purple) of adult Bicknell’s Thrush captured and recaptured in Vermont from 2001 to 2015. The orange line is the annual ENSO precipitation index (ESPI) values for the wintering habitat on Hispaniola (high values indicate wetter winter conditions); apparent survival of thrushes bumps up in wet winters. An “M” above the X-axis showing year, indicates that mature fir cones were present in our study area from September through the subsequent breeding season; 2002 was the first mast year within our study period, for example. Bicknell’s Thrush apparent survival was highest in these ‘mast years’. Both mast year status and ESPI were biologically informative covariates describing nearly 30% of the temporal variation in apparent survival.

So clearly, we don’t fully understand why thrushes are more likely to return to Mt. Mansfield in summers that happen to have lots of squirrels. It’s possible that cone production is associated with increased food availability for thrushes in the following summer—something that the VCE team was unable to quantify for that 15-year period. Maybe the abundance of food outweighs the risk of depredation. Mast production by fir trees is highly synchronous across New England mountains, so perhaps squirrels are common “everywhere” at high elevations in those summers, and the thrushes just can’t escape the risk of nest predation by relocating to a new mountain. Those research avenues, however, will have to sit on the back burner for awhile.

Until then, I’m working on a project with researchers from New York and Indiana to document the upslope movement of New England montane birds in response to warming temperatures from climate change. Data from multiple other mountain systems around the world already show other montane species moving upslope at a rate of approximately 11 m per decade, following rising temperatures and changing precipitation gradients. I suspect we’ll find a similar pattern for our northeastern montane bird communities.

I’d be happy, however, for the data to reject my hypotheses again.

Citation: Hill, J.M., J.D. Lloyd, K.P. McFarland, and C.C. Rimmer. 2019. Apparent survival of a range-restricted montane forest bird species is influenced by weather throughout the annual cycle. Avian Conservation and Ecology 14(2):16. https://doi.org/10.5751/ACE-01462-140216.

I really enjoyed your article. I have yet to see the Bicknell’s Thrush (target bird when hiking Mt. Abraham), but what I enjoyed more is the insight you provide to real science…it is data driven despite how much we might love our favorite hypothesis. Thanks.

Thank you John, I really appreciate that. Are you referencing Vermont’s Mt. Abraham, or another state’s? If you’re talking Vermont then let’s try and find one together this summer up there. I haven’t hiked that mountain before, and I’m curious to know if they’re there. Please send me an email. All the best, Jason

Nice article. You mention in the article that all of the birds that migrate from Vermont in autumn will return the following spring, I have one question where do all the birds go in autumn?

Hey y’all,

Thanks for your question. Our models estimate that about 90% of Bicknell’s Thrush head to Hispaniola for the winter, with fewer numbers on Cuba and Puerto Rico. A nice summary here (https://vtecostudies.org/projects/caribbean/forest-bird-research/bicknells-thrush-winter-ecology/). So Bicknell’s Thrush really occupy a narrow geographic breeding and wintering range–both of which create their own conservation challenges. All the best, Jason