Ghosts from the Arctic

Like ghosts from the Arctic, snowy owls have descended from the far north this winter. They’re showing up in fields, along highways and even in a few backyards. These migrations southward from the arctic tundra are a birdwatcher’s dream. And like dreams themselves, they are neither predictable nor fully understood.

The classic theory held by ornithologists to explain the irregular migrations of snowy owls to this region has always centered on lemmings, a favorite food of the owls. These small rodents undergo population booms and busts. About every four years lemmings become incredibly abundant. Many scientists believed that after the lemming populations eventually crashed, snowy owls would head southward in search of food. Intensive research now shows this may not be the case.

Norm Smith, director of Massachusetts Audubon’s Blue Hills Trailside Museum, has been monitoring snowy owls for more than 25 years at Boston Logan Airport. The broad stretches of land around airport runways tend to look like tundra and become a winter Mecca for wayward owls. But Smith and others have discovered a twist to the old migration theory. We actually see the most snowy owls in New England during lemming population boom in the arctic, not after the lemming population has plunged.

It takes lots of meat to raise a snowy owlet. Researchers have estimated that a pair of snowy owls and a brood of nine owlets eat 1,900 to 2,600 lemmings during the breeding season from May to September. That’s about 325 pounds of rodent meat. Lots of lemmings allow for lots of owls, and when younger owls start outgrowing their natal territory, the adults chase them away. They have to find somewhere else to dine, which often means flying southward.

Smith and other ornithologists can count the number of young owls each winter. That’s because young snowy owls have plumage that is slightly different than their parents. Young females have extensive dark lines throughout their feathers giving them a black and white zebra pattern. While young males have a pure white bib under their chin and the back of their head is entirely white.

Using a real-time, web-based program, birdwatchers are helping too. Launched in 2003 and managed by the Vermont Center for Ecostudies, Vermont eBird (www.ebird.org/vt) has revolutionized the way that the birding community reports and accesses information about birds in Vermont and beyond. A simple and intuitive web-interface engages thousands of participants to submit their observations or view results via interactive queries into the massive eBird database. One owl observation at a time, birdwatchers are helping scientists monitor and solve some of the mysteries of owl migration.

The winter invasion of 2013-2014 was of historic proportions. Snowy owls were found in incredible numbers throughout Vermont, including one in downtown Rutland. Although not as large as last year, this winter has proven to be above average again, with regular sightings reported to eBird throughout the Champlain Valley.

With small GPS units secured on the backs of owls, ornithologists with Project SNOW Storm are able to witness the amazing flights by these owls. Weighing just a fraction of the weight of an owl and worn like a small iPhone backpack on the owls, these small solar-powered transmitters record the latitude, longitude and altitude at regular intervals day after day. But unlike conventional transmitters that report data to satellites orbiting the earth, this cutting-edge technology uses the cellular phone network. When a bird is far away from a cell tower, such as in the Arctic far away from infrastructure, the data is stored in the unit. When the owl flies within range of a cell tower, it phones home. All of the data is transmitted to the ornithologists.

Project SNOW Storm has uncovered some of the mysteries of the Arctic ghosts that are here for the winter. Some are homebodies, occupying just a half-mile home turf. Others were wanderlust, flying back and forth across hundreds of miles over just a few weeks. Each bird likely fitting their behavior to food.

Some snowy owls in the Great Lakes lived for weeks on the ice, likely hunting ducks and geese that spend the winter floating among the cracks and open areas of the ice sheets. Adult owls in the Arctic are known to spend their entire winter along open areas of water in the pack ice hunting sea ducks.

Farther south, here along the Atlantic coast, the owls have no sea ice. Surprisingly, they hunt ducks, geese, gulls and grebes in the open ocean at night, often using ship channel markers and buoys to perch and hunt.

Smith has discovered that snowy owls that winter in Massachusetts spend summers in northern Quebec and Baffin Island, sometimes above the Arctic Circle. Some take a northwest route through Vermont on their spring trip back to the tundra.

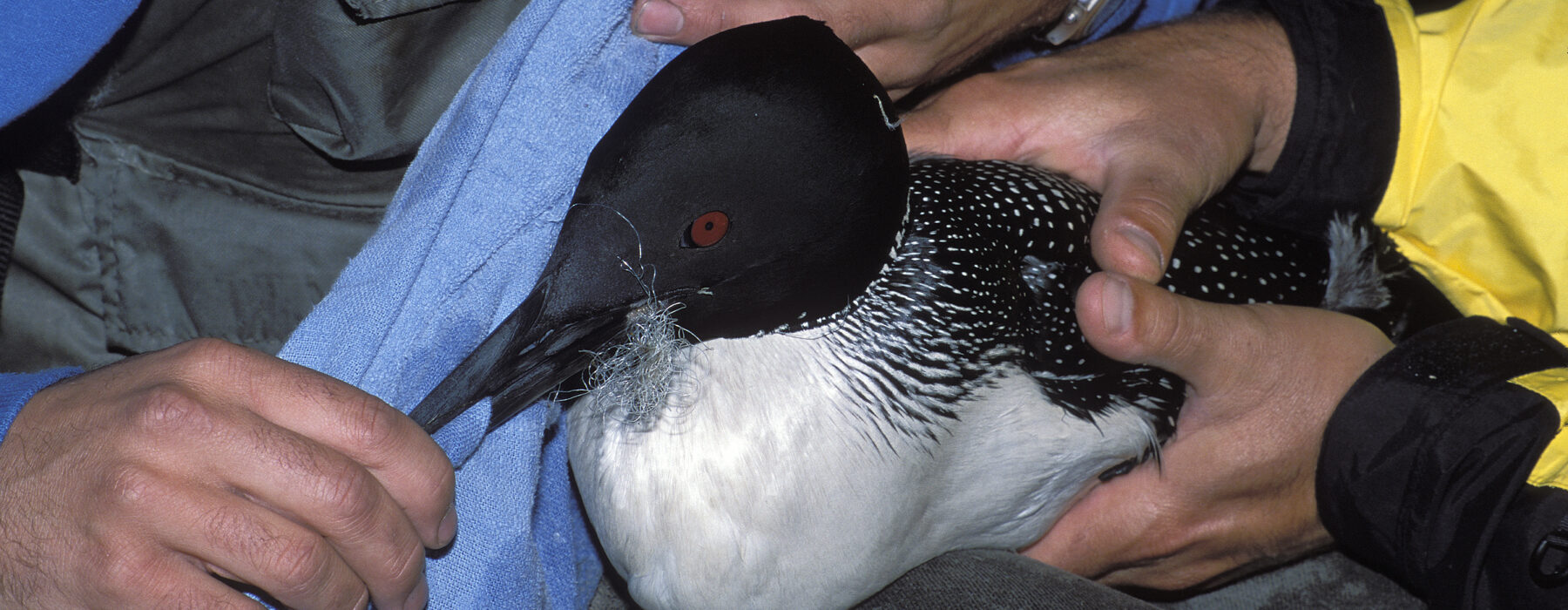

Take the 100th owl captured by Smith last year at Logan Airport in Boston. Snowy owls love the environment at Logan. Nestled right on the bay, there’s plenty of food and the vast, treeless area harkens back to their home turf in the Arctic tundra. Smith can trap the owls at the airport, but he can’t release them there do to concerns they may threaten aircraft. So, he hauled this owl northward to the more quiet Plum Island refuge at the mouth of the Merrimack River to release her.

Weighing almost 6 pounds and carrying a GPS transmitter, Smith released the bird on March 15. She didn’t stay there. Over the winter she traveled back through Boston, into Rhode Island and Connecticut, up the Connecticut River and over to the Saratoga Lake region in New York. On April 6th she went silent.

She didn’t phone home for nearly 8 months. On November 30 the GPS unit reported her travels. After going silent she flew to the southern Lake Champlain shoreline and stayed for a few days. In the evening darkness of April 9th she took off northward flying straight up the lake, crossing through Montreal and eventually arrived on the breeding grounds on the Ungava Peninsula in far northern Quebec, 1,300 straight miles from her Vermont visit (see a map of its travels).

In winter, snowy owls are bird eaters, capable of taking prey much larger than themselves. Smith reports he once witnessed a snowy owl take flight from a lamp post near the airport and accelerate toward a great blue heron that had just lumbered into flight along the shoreline. Much to Smith’s surprise, the owl punched the bird to the ground to make for one very big meal.

Humans have admired snowy owls for centuries. Their images have even been found in ancient cave paintings in Europe. This year, whether stoically watching over a field in Vermont or hunting along a runway at Boston Logan Airport, surprised birders are sure to stare at them in awe. This magnificent bird reminds us that these seemingly far off landscapes are bound together through the ghostly flights of the snowy owl in their annual quest for food.

Note: This was published in Rutland Magazine, Spring 2015

Wow. I did not know about project snowstorm. I could get lost on that site for a very long time. Fascinating stuff. Thanks for all of the great updates.

These blog posts certainly help chase the winter away.

Agreed! The maps of their movements are amazing.