Leaf it Be — ditch the rake this fall to promote insect populations around your home

by Jason Hill and Abbie Castriotta

White-throated Sparrow (Zonotrichia albicollis) foraging in leaf cover © darontansley

As fall rolls through and the colors on the asters (Symphyotrichum species) and goldenrods (Solidago species) fade, it’s easy to be lulled into a sense that the growing season has finished. But that’s far from the case. Over winter, carefully managed flower gardens and yards will grow a crop of pollinators and other invertebrates for next year. These are the insects that will pollinate our gardens, and ensure a future supply of food for birds and amphibians after migration and hibernation is complete next spring. Indeed, the growing season has just begun and autumn is a critical time to think about how we can bolster insect populations around our homes.

First, fall is a great time to reassess the flowering plant diversity around our homes to ensure that blooming native plants are available as nectar resources for the many pollinators that are still active. For example, queen bumble bees (Bombus species) visit flowers through October as they gather nectar before heading underground to hibernate—ensuring your yard has blooming plants in October is an investment in future bumble bee populations. As of this week, local nurseries still have actively-blooming, native plants such as asters and goldenrods—the two groups of plants that likely support the most butterfly and moth species in our New England landscape, according to Entomologist Doug Tallamy at the University of Delaware. Many native flowering plant species require cold stratification for their seeds to germinate (e.g., Canadian Bunchberry [Cornus canadensis], goldenrods, Bloodroot [Sanguinaria canadensis] Beebalms [Monarda species], and Common Milkweed [Asclepias syriaca]), so for a thriving, pollinator-friendly yard next season, it is crucial to plan ahead and plant now. Check out the Wild Seed Project in Maine for native plant seeds that you can still plant this autumn.

Common Eastern Bumble Bee (Bombus impatiens) visiting late-season flower © Kent McFarland (left). Aster and Goldenrod (Symphyotrichum sp. and Solidago sp.) © Melinda Young Stuart (right).

Second, as our colleagues at the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation like to say—leave the leaves! Resist the urge to manicure the space around your home and leave those leaves where they lay. Leaf cover on the ground over the winter protects bare ground from erosion and desiccation. Leaf layers more than 2 inches deep can sometimes smother lawns, so consider raking the early leaf falls and leaving the later leaves where they fall. Pile the raked leaves atop your gardens and flowerbeds, and use the leaves as mulch around shrubs and trees. Insect eggs, larvae, and adults take shelter among the leaf litter, so resist the urge to shred the leaves. Just a sampling of the myriad of insects and life stages that overwinter in leaf litter include the eggs of Great Spangled Fritillaries (Speyeria cybele), the pupae of Luna Moths (Actias luna), the larvae of Baltimore Checkerspots (Euphydryas phaeton) and Isabella Tiger Moths (aka Wooly Bears, Pyrrharctia isabella), and bumble bee queens.

Isabella Tiger Moth (Pyrrharctia isabella) caterpillar © Nathaniel Sharp (left). Baltimore Checkerspot (Euphydryas phaeton) larva © Susan Elliott (right).

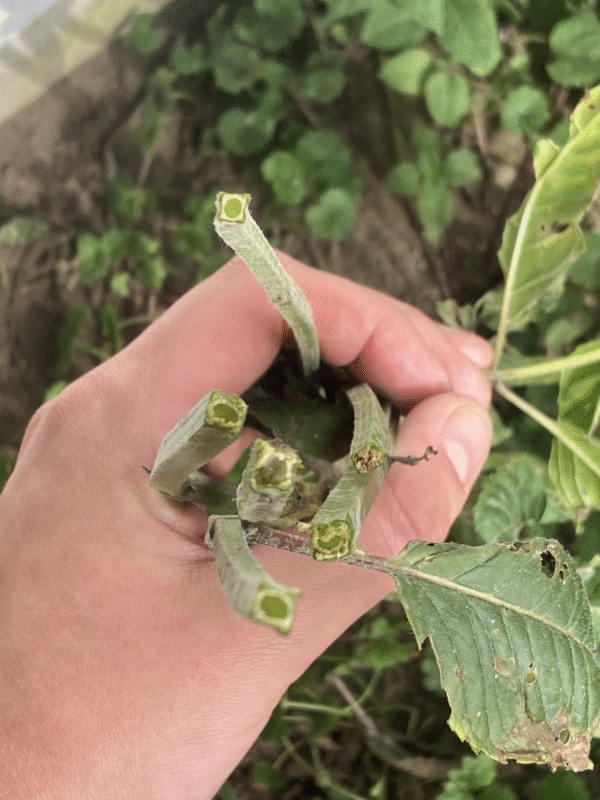

Leaving Beebalm (Monarda species) and other perennial stems intact over the winter is best, but if you feel compelled to “tidy up” then consider the compromised approach of cutting the stems 1-2′ above the ground (as seen here) to serve as a potential home for invertebrates over the winter. © Kevin Tolan

Third, leave rigid standing dead vegetation as homes for insects that overwinter as eggs, larva, and adults. For example, leafcutter bees (Megachile species) and some mason bees (Osmia species) overwinter as larvae in the hollow stems of plants around our homes. So instead of leveling your perennial wildflower garden flush with the ground in the fall, put the sheers away and leave your seed heads and perennial flower stalks intact over winter. The following spring, cut the stems at a variety of heights between one and two feet, bundle the cut pieces, and stash the bundles in your yard to provide even more habitat for spring-breeding insects. If you feel really strongly about tidying up the yard in the fall, and you’re compelled to cut back perennial wildflowers, then consider the intermediate approach of leaving one to two feet of rigid stems intact. Here in New England, many butterfly species overwinter as chrysalises on standing dead plants, including some of our swallowtails (Papilio species), sulphurs (Colias species), elfins (Callophrys species), and skippers (Hesperiidae)—another reason to leave rigid dead vegetation. Furthermore, by leaving seed heads, you will be providing a food source for birds and other winter wildlife.

Pugnacious Leafcutter Bee (Megachile pugnata) © Mike Kiernan (left). Luna Moth pupa (Actias luna) © Susan Elliott (right).

Take this as an excuse to ditch the rake, spend the weekend on the trails instead, and rest easy knowing that your yard will be a winter safe haven for biodiversity.

For more insight, check out Nesting & Overwintering Habitat for Pollinators & Other Beneficial Insects by the Xerces Society, Doug Tallamy’s book Bringing Nature Home from Timber Press at your local bookstore, and Heather Holm’s YouTube talk on creating insect habitat around your home.

Thanks Abbie – I sent this around to our Master Gardener chapter, plus shared with the local elem. school (this month’s science topic is insect life cycles)

Thanks to Kate Kruesi for an important correction to an earlier version of this article about when to cut back wildflowers, and thanks for her suggestion to check out the Burlington Grow Wild initiative (https://burlingtonwildways.org/get-involved/grow-wild).

I also got a great email asking about converting lawn to wildflowers. At our house, we have been systematically converting our lawn to vegetable and flower gardens over the last 6 years, and we’ve tried a bunch of approaches. We find it’s easier to ‘knock off’ sections of your yard in the spring (as opposed to the fall)–doing a manageable amount each year. Benefits of a spring lawn conversion: 1) there’s a lot more options of species to plant, 2) you don’t have to worry about protecting bare soil from wind/water erosion over the winter (e.g., with straw cover or landscape cloth, which also wants to blow away in the winter winds), and 3) the wet soil makes sod/lawn easier to remove in large pieces IMHO. Perhaps I’ll do another post this spring on lawn conversion.

Just available, how appropriate! I have the “Pollinator Habitat” sign in my yard. https://gifts.xerces.org/products/leave-the-leaves-sign