My Summer in Species: Illustrated

Hello! I’m Gita Yingling, and this summer I worked with VCE as an Interdisciplinary Intern. Through this position, I had the chance to work with five different staff members and learn about different types of fieldwork, data collection, data analysis, and science communication! By being able to dip my toes into a little bit of everything, I got to learn first-hand that there are so many ways to be a scientist, and so many wonderful subjects to study.

My field experiences took me all across beautiful Vermont. As I drove along green highways, I felt so honored to study in a state that is incredibly biodiverse in flora and fauna. As both a budding scientist and an artist, I combined my interests and created illustrations of my favorite species I encountered during my work to tell you all about my summer internship experience.

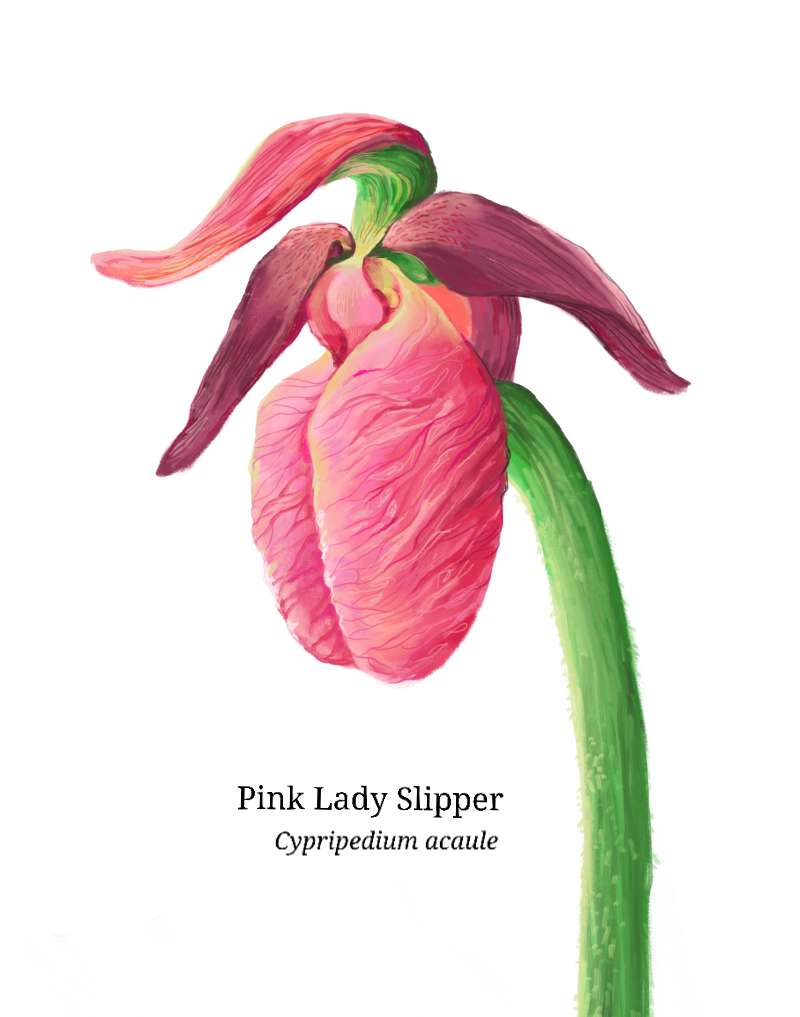

Pink Lady Slipper

During my first week, I hiked to the top of Mount Cardigan in New Hampshire with my fellow interns and some VCE biologists. Despite being eager to see the view of the White Mountains at the summit, we stopped every 20 feet to identify a new plant, listen to a bird song, or try to find a salamander under a log. One species we saw was Pink Lady Slipper (Cypripedium acaule), a distinct wildflower belonging to the orchid family! These orchids are very recognizable, making them a popular flower to seek out along trails during summer hikes. Their elegant beauty isn’t the only special thing about them; these pink orchids have a symbiotic relationship with a fungus in the soil that belongs to the Rhizoctonia genus.

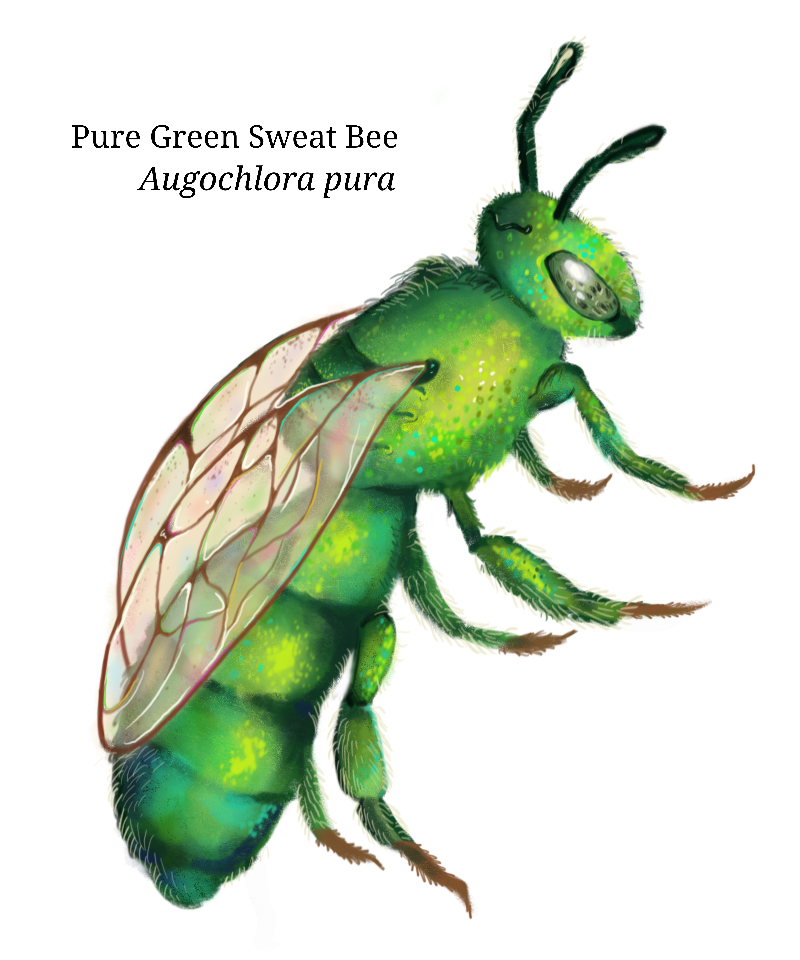

Sweat Bee

Early in the summer, I traveled to Connecticut’s coast with the other summer interns and Dr. Desirée Narango to survey a pre-restoration property for pollinators, in partnership with Connecticut Audubon (you can read more about this study here). Through our three days of sweaty fieldwork in Westport, we recorded and collected as many pollinator species as possible to gain insights into the health of the ecosystem. One of the key species we sought out when surveying the plots was Augochlora pura (often referred to as the Pure Green Sweat Bee), a small sparkly insect that happily pollinates a wide variety of plants. Since Connecticut Audubon wanted to know the existing biodiversity of the preserve before putting energy towards restoration, every time we saw the green glint of a sweat bee, it was a great sign.

Loons

As I made my way up to the Northeast Kingdom, I felt loony with excitement to study loons and work on management of their nesting sites. Everyone who has heard their haunting call, met their red-eyed gaze, or seen them gliding serenely on a lake becomes enraptured. Despite my newfound passion for loon conservation, I had never seen one before; however, my work this summer left me with a new understanding and appreciation of them. My favorite loon experience took place on a sunny morning. We had canoed out on Noyes Pond in Groton, Vermont, with VCE’s Seasonal Loon Biologist Eloise Girard and were on a mission to check the band colors of a reportedly rowdy bird that terrorized fishermen on the pond. We wanted to figure out where the bird had come from since it was not hatched on that pond. After patiently luring it with a fake fishing rod, we were able to make out four bands, two on each leg. We sent the findings to someone who had access to the loon’s records. When we heard back, we learned that our loon—which had a blue dot/yellow on the left and red/silver on the right—is an adult male that was initially caught after landing on a wet road near Mountain View Lake in Bellmont, New York, almost a year ago, and was later released on Lake Colby in Saranac Lake, New York. This information was fascinating because it tells us the loon has ended up about 130 miles away from its release site. We all agreed it would be very interesting to know if the same bird comes back each year to continue wreaking havoc on Noyes Pond!

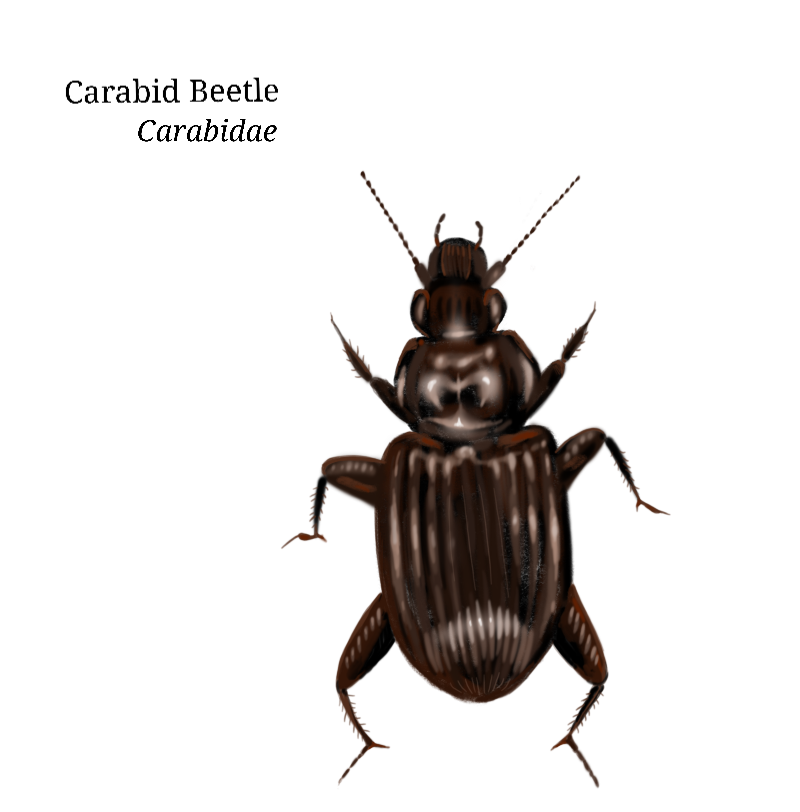

Carabid Beetles

Working with Field Ecology Intern Zoey Pickett, my fellow Interdisciplinary Intern Pia Carman and I navigated through woody terrain at Underhill State Park and the Teardrop trail on Mount Mansfield. Each week, we went to these areas to check a total of 48 pitfall traps. The insects in each trap will help shed light on what food is available to birds in the area. Another main purpose of this work was to find Carabid beetles: ground beetles of the genus Carabidae. We took the contents of the pitfall traps back to VCE’s lab and sorted them. The goal of finding the Carabid beetles is to recreate a study that the University of Vermont originally conducted 30 years ago. This study measured and analyzed Mount Mansfield’s biodiversity. Decades later, VCE will compare its findings with the original study to learn more about species’ trends. The Carabid beetle count will show us how populations have changed, especially along elevational gradients as the effects of climate change become more pronounced.

Bicknell’s Thrush

Getting to spend two nights on Mount Mansfield with the 2024 banding team was my favorite internship experience. Before I even got to the mountain, I spent days working in the office alongside paintings of the elusive Bicknell’s Thrush. As I worked, this charming and beloved bird could be seen at every turn, making me even more excited to have the chance to work with them. As climate change and human-driven land change apply pressure to these songbirds’ survival, they need all the support they can get. Given that, imagine my excitement when, after many strenuous net runs, I got to see a young Bicknell’s Thrush and observe it being processed and released first-hand. Although I loved all of the bird species I had the chance to see on Mansfield, especially young Dark-Eyed Juncos, my favorite was undoubtedly the special thrush. I now carry with me fond memories of early mornings and cloudy afternoons assisting with mist netting, seeing banding in action, quickly writing down the banding data, and the palpable excitement in the air whenever a Bicknell’s Thrush was caught.

Beach Heather

Toward the end of my summer internship, I traveled over to the Champlain Valley with VCE’s Director of Conservation Science, Ryan Rebozo, to study rare plants and do some population monitoring. This included visiting various sites where rare species had been reported in order to remove invasive species and allow more room for the rare species to grow and thrive. One of these sites was near the shore of Lake Champlain, a small sand plain where a humble plant called Beach Heather (Hudsonia tomentosa) grew in patches. This shrub often forms dense mats in sandy environments and is easily identified by its yellow flowers or, if it’s not in bloom, by its scaley, needle-like leaves that help retain moisture. Beach Heather acts as an indicator species to the health of its ecosystem, as well as a stabilizer in sandy soils. Despite its important ecological role, it has now become a rare plant due to increasing development and decreasing sand plain habitat. By removing invasive species from this site (such as cutting back encroaching honeysuckle bushes), measuring tree cover, and taking a rough count of how many individual heather plants are currently present, we are taking a step toward conserving this valuable yet threatened plant.

As a new Vermonter, my journey all across this beautiful and biodiverse state opened my eyes to the plethora of species that call Vermont home. Having the chance to work directly with biologists who are so passionate about conservation and research was a valuable experience that I’ll carry with me into my next steps as a student, scientist, aspiring science educator, and human being growing up and living with the imminent effects of climate change.

Wonderful illustrations! Thanks for sharing!