Poison in the Pools: Mercury in Vernal Pool Amphibians

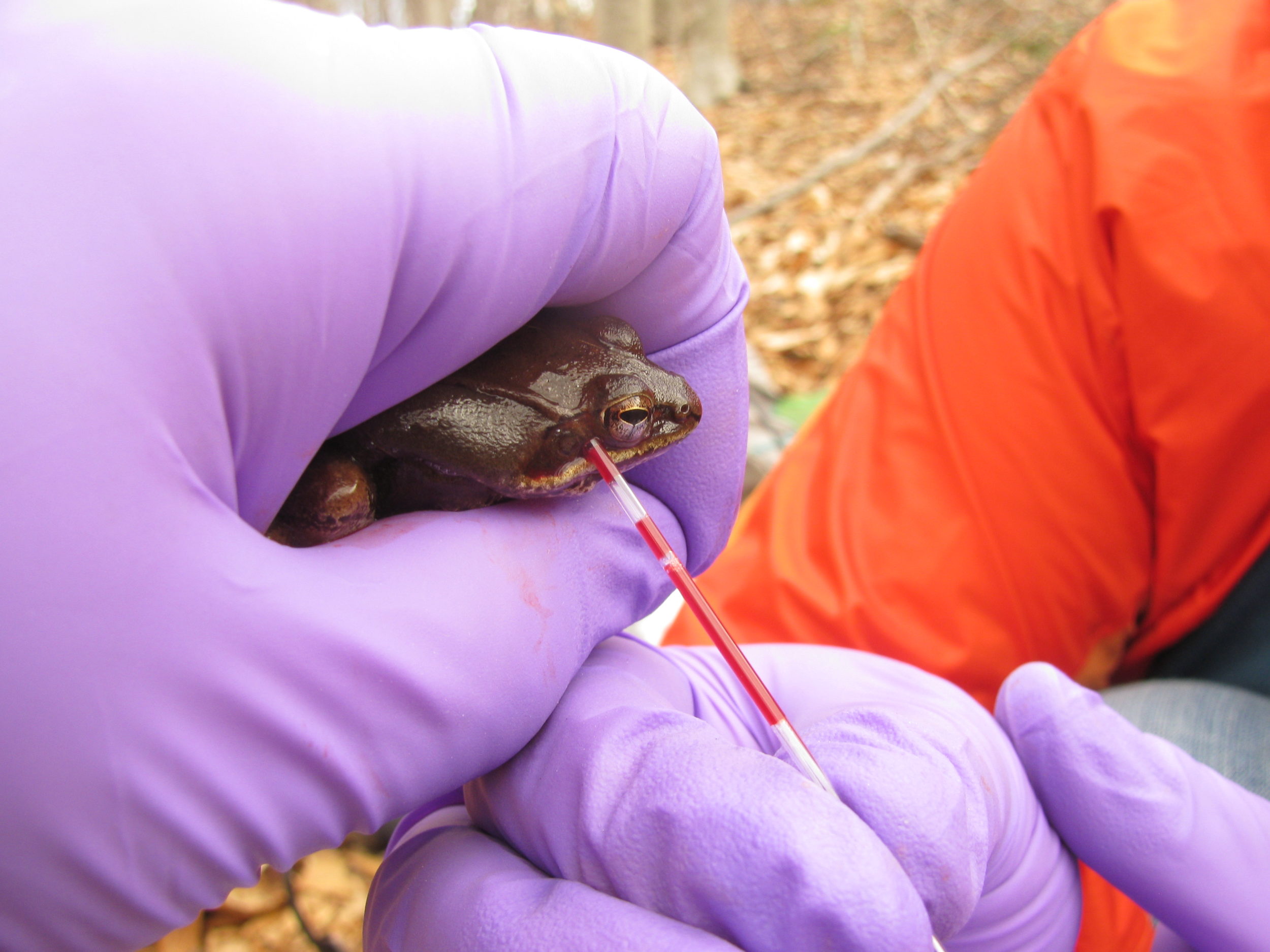

Collecting a blood sample from the facial vein of a Wood Frog for mercury analysis. / © Steve Faccio

VCE has a long history of investigating mercury concentrations in wildlife—particularly in montane ecosystems and Caribbean birds. Recently, our groundbreaking investigation of mercury levels in vernal pool foodwebs (in collaboration with Dartmouth College Research Associates Dr. Vivien Taylor and Dr. Kate Buckman) has resulted in the project’s first paper, Bioaccumulation of methylmercury in wood frogs and spotted salamanders in Vermont vernal pools. The paper is published in the journal Ecotoxicology.

Mercury (Hg), and its more biologically available form, methylmercury (MeHg), are powerful neurotoxins that impact development and function of the central nervous system. A naturally occurring element found in the earth’s crust, mercury is generally inert. It becomes a problem when it is released into the atmosphere—primarily through coal-fired power plants and industrial incinerators—dispersing widely before falling back to the ground via precipitation. Under certain environmental conditions, anaerobic bacteria convert this re-deposited inorganic Hg into its organic and more toxic form, MeHg, and it enters the food web. The Northeast is considered a mercury “hotspot,” due largely to our position downwind from airborne emissions that originate in the industrialized Midwest.

Surprisingly, fewer than a handful of studies have examined mercury in vernal pools, even though these small ephemeral wetlands provide critical breeding habitat for several species of amphibians and a diverse assemblage of invertebrates. Moreover, vernal pools support a variety of landscape and geochemical conditions that both enhance mercury transport into pools and facilitate its transformation to MeHg.

Co-authors and Dartmouth Research Associates, Dr. Vivien F. Taylor (left) and Kate L. Buckman, collecting water samples from a vernal pool in Sharon, VT for mercury analysis. / © Steve Faccio

To determine MeHg concentrations in amphibians, we intensively studied six vernal pools in the Upper Valley area of Vermont, collecting samples of Wood Frog and Spotted Salamander eggs and larvae, as well as blood and tissue samples from adults of both species. In addition, we collected monthly water, soil, and leaf litter samples for Hg analysis.

An adult Spotted Salamander being weighed before collecting blood and tissue samples for mercury analysis. / © Steve Faccio

Our results showed that MeHg concentrations of pool water varied considerably between pools due to a variety of factors, including water chemistry metrics such as pH, dissolved oxygen and dissolved organic carbon, water temperature, and the type of forest around each pool (pools surrounded by coniferous forest had higher mercury levels than those surrounded by deciduous forests). In general, MeHg levels in the water tended to increase from spring through summer, coinciding with increases in water temperature and decreases in dissolved oxygen as pools dried.

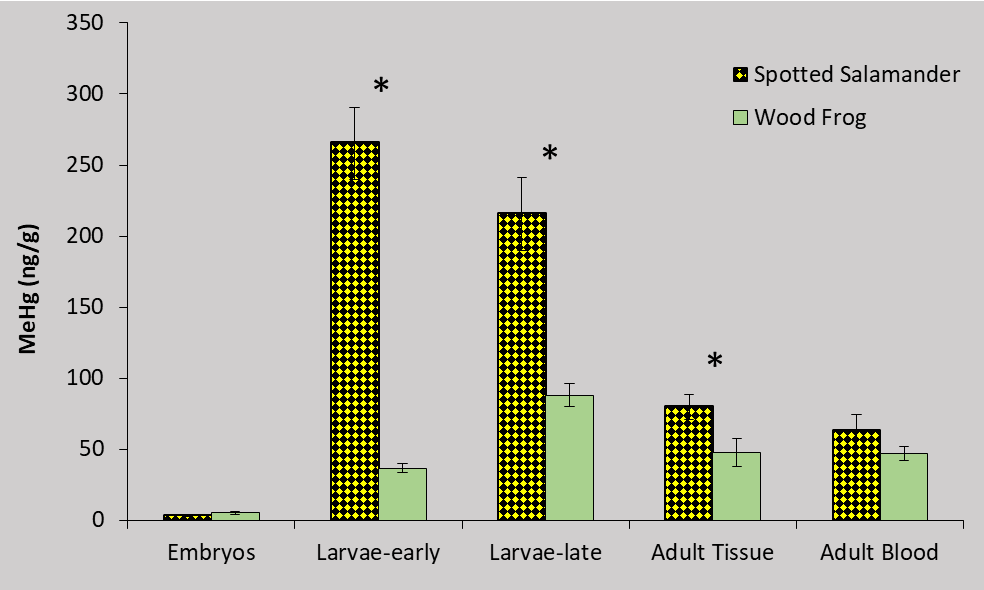

Mercury levels in amphibian eggs were relatively low—similar to that of the surrounding water—suggesting that females did not off-load mercury burdens when depositing eggs. However, we found that MeHg bioaccumulated rapidly in predaceous Spotted Salamander larvae (~50 to 100 times greater than their eggs), and moderately in omnivorous Wood Frog tadpoles (~10 to 20 times greater than their eggs) (see chart). This has significant implications for any wildlife that feed on amphibian larvae, including a variety of vernal pool invertebrates such as diving beetles, backswimmers, dragonfly larvae, and others, as well as Eastern Newts, snakes, and birds.

Methylmercury (MeHg) concentrations in Spotted Salamander and Wood Frog eggs (dry weight), larvae (dry weight), and adult tissue (dry weight) and blood (wet weight) from Vermont vernal pools. Asterisks indicate significant difference between species within life stage.

Among adult frogs and salamanders, MeHg levels were roughly one-third to one-half that found in their larval stages, probably because terrestrial adults are exposed to lower Hg concentrations than aquatic larvae (see chart). Adult Spotted Salamanders had significantly greater amounts of MeHg compared to Wood Frogs, which is likely due to their longer life span (20-30 years) compared to Wood Frogs (3-5 years). These results are the first to report Hg levels in Spotted Salamanders and adult Wood Frogs.

Our work demonstrates that vernal pools are important hotspots of mercury bioaccumulation, and that vernal pool amphibians may represent a significant source of mercury ingestion to terrestrial predators. Unfortunately, little is known about how mercury levels affect amphibians. Laboratory studies indicate frog tadpole sensitivity to MeHg is highly variable among species. For example, Wood Frog tadpoles showed no adverse effects at concentrations 2-3 times those that we detected in the field, while Southern Leopard Frog tadpoles showed reduced survival at levels well below those we documented. Among Marbled Salamanders, larvae experienced 50% mortality at mercury levels 2½ times lower than those we detected in Spotted Salamander larvae.

In recent years, EPA regulations have led to demonstrably reduced Hg emissions through the Clean Air Act. Unfortunately, the current administration continues to rollback many of these advances, casting a dark cloud of uncertainty on the future of this dangerous toxin’s presence in our environment.

Lynnwood and Jack,

If you have not seen this it may interest you.

Don

Lynnwood, this may interest you if you have not already seen it.

Don

Very important work by VCE. While our protests on behalf of the poisoned environment move things along in necessarily dramatic fashion, it’s factual evidence that will inform the policy of a restored world. If there’s time…