The Colby Loon

By Rose West, VCE’s 2019 Alexander Dickey Conservation Intern

July 17th, 6:04 PM

Twelve hours and a few hundred miles later, my day working on the Vermont Loon Conservation Project lingers on. At each of the waterbodies I visit, I assess and observe these once-threatened “tuxedo birds.” I seek answers to various questions that will help determine each individual loon’s life cycle stage. Two loons swim close together: is that a potential pair or a territorial dispute? Is there any nest-building? Are they using the nesting raft or the natural landscape? Is this lone bird an intruder? On my visits later in the season, I have even more questions. I return and look for hatchlings, small and buoyant. I investigate any potential causes of nesting failure: remnants of shells—likely predators; cold eggs, left unattended—likely disturbance-induced incubation failure. Did the pair renest?

However, this day I had a different question to answer at Colby Pond, the next in my procession of ponds to visit: was this loon okay? It was an atypical question prompted by a report from a vigilant volunteer who expressed concern over a loon beaching itself at Colby Pond. VCE’s loon biologist, Eric Hanson, asked me to investigate and provided detailed instructions on how to assess the situation.

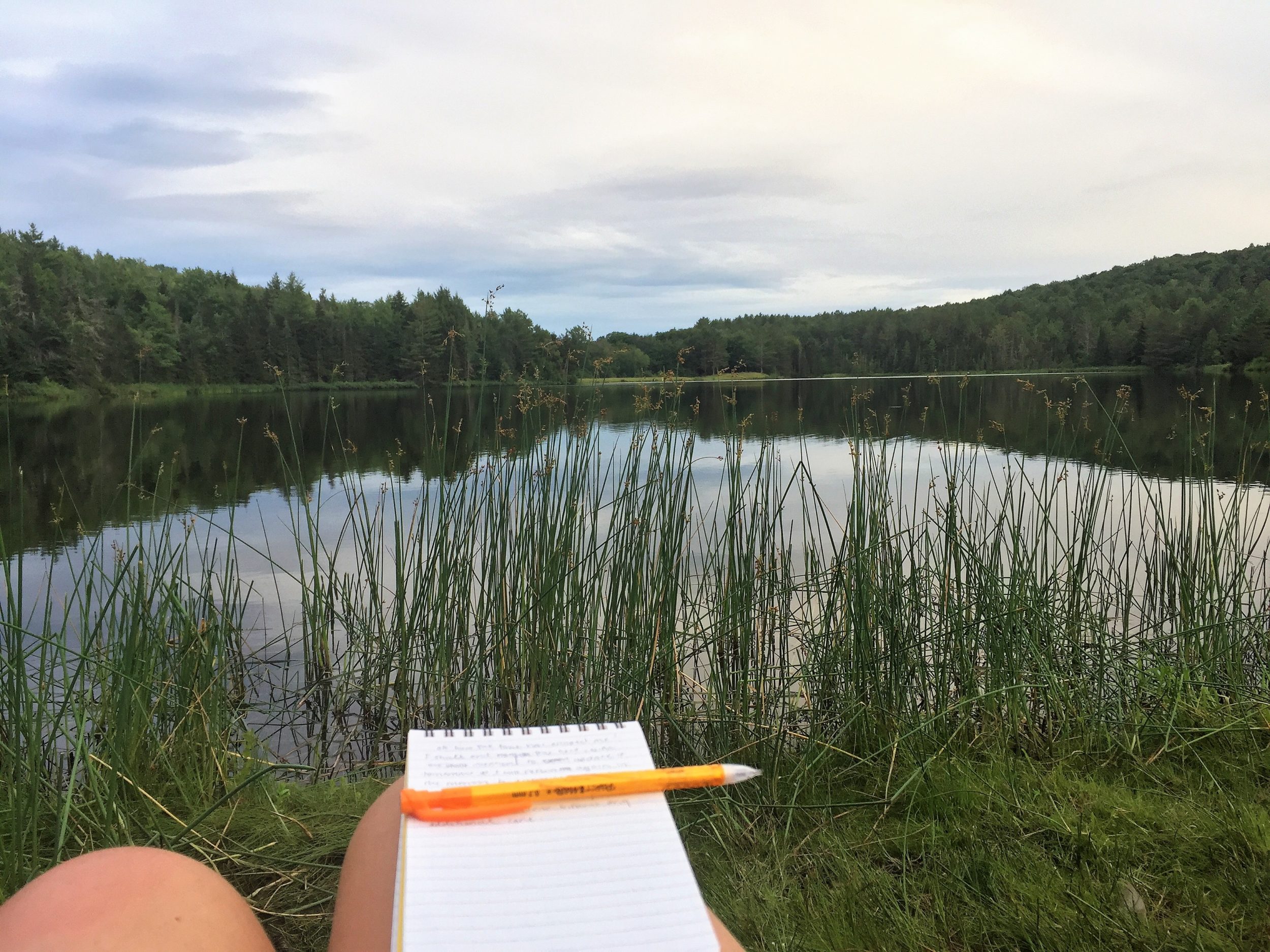

Eric’s primary instruction, guiding me now, is “wait and watch.” So here I sit, criss-cross on my paddle board, notebook in hand, grateful for the opportunity to record this remarkable experience as so many others have gotten lost in the fast flowing pace of loon monitoring work. Thus, I’ll now share, to the best of my ability, my current moment.

The focal loon, possibly injured, is off to my left, tucked away and concealed in tall, green reeds along the shoreline. Through my binoculars its white, patterned collar is striking and reflects on the placid water, complemented by the starkly contrasting deep green conifer shoreline and gray sky. Two other loons (a potential breeding pair) have demanded my attention as one emits a drawn out melancholy call—the wail—which is essentially akin to a game of ‘Marco Polo’ as loons attempt to locate one another. The focal loon doesn’t reply. This interaction provides insight that the focal loon may be an intruder and the situation may have been the result of a failed claim on the other loon’s territory. However, I note this is pure speculation for now.

A few minutes pass, and across the pond I hear an intense flapping. A goose? There is a group of approximately seven lurking about. No, it’s the labored take-off of the male member of the resident loon pair. The sound of wings beating, a hearty and fast-paced whooshing, is distinct as the loon heads directly towards me. My own heart rate matches the pace. After barely clearing my head, he begins to circle the perimeter of this small pond, certainly to gain needed momentum. I am relieved the take-off was a success at all, since a loon can become stranded on small waterbodies like this. Whoosh, whoosh, whoosh—the female takes to the air as well, and I take note of her thinner neck and smaller size. Circling twice they join together in graceful unison and head southwest over the tree line, perhaps seeking better fishing opportunities on the nearby, larger lakes.

Now that the pair has vacated the pond, the focal loon has moved from its vegetative hiding spot onto the open water. I do a full visual evaluation of its condition, and note that a single feather is out of place, frayed and jutting straight up on the right wing. Is this indicative of a more substantial injury? I focus on Eric’s second instruction—see how it swims. When I first arrived, I met VCE’s Susan Hindinger who had stopped by to check in as well. She informed me that prior to my arrival the loon was beached on the boat launch. She took care to move it carefully, towel draped over its head and body, to an area with less human disturbance. With this in mind, I watch as the bird slowly meanders through the shallows, head down beneath the surface of the water, and consider it a great improvement. It is hunting, but with obvious mobility issues. Loons are known for their deep dives that average 30-40 seconds. During the next half hour I follow its path through my binoculars and note that the loon never made a full dive, just periodic plunges of no more than five seconds. In our short time together, I already hold high affection and awe for this creature.

The arrival of dusk is met with croaking bullfrogs and a sunset bird chorus. The songs and calls of Black-capped Chickadees, Red-winged Blackbirds, and a lone Belted Kingfisher are the few I can identify. Others I still yearn to learn. I note how different this aquatic ecosystem is from the montane spruce-fir ecosystem which has been my classroom for the start of my birding education with VCE this summer. The focal loon has drifted around a small point, beyond my line of sight. The time reads 7:57 pm, Oh how time has escaped me! I will end this here, as a familiar friend, a Winter Wren—one of the focal species for VCE’s Mountain Birdwatch—sings its boisterously bubbly song as I depart.

July 18th, 8:00 AM

I have arrived to an overcast morning sky and still water. Three loons are immediately prominent within Colby Pond’s small boundary. They are all situated in the center, fairly close to one another and exchanging small hoots as if having a morning chat. Is it possible the focal loon is among them? I cannot distinguish a misplaced feather, but one bird separates itself by taking off and landing again at the opposite end of the pond. I experience an immediate feeling of hopefulness that the focal loon could be maneuvering so well. Soon however, all three pick up and leave: the pair heading off together in the same direction as yesterday and the other in the opposite direction. An orange kayak is heading towards the boat launch, its paddler a dedicated volunteer who spent his early morning hours keeping an eye on the injured loon. He is cheerful and informative; he tells me the focal loon is still on the water, “dabbling like a duck.” He offers his phone number and tells me to call if I need any help with a loon round-up, then takes off to continue monitoring other lakes on Route 100.

I slip onto the water on my paddle board. It takes a little while but I see in the nearby shallows the upright feather, the focal loon. I follow from a distance and observe its spearfishing efforts, slow-going and from what I can tell, unproductive. Here are a list of actions I take note of:

- another loon flies in and makes a splash-landing, inspiring the injured loon to make a 12-second dive.

- a small silver fish jumps directly over the injured loon’s head, but the loon doesn’t take notice.

- a 13-second dive after a tremolo call from yet another loon flying overhead (this loon doesn’t land).

- a 24-second dive as one of the other loons on the water approaches; the focal loon then retreats into the reeds. The latest event caused it to start heading back in my direction; seemingly unconcerned by my presence, it comes as close as two meters away!

- the focal loon nabbed a fish after a shallow dunk, and swallowed it whole after some effort on the surface of the water.

Once it makes a full circle around the perimeter of the lake, I head back to shore, more confident in the bird’s ability to hunt, and curious of what appears to be heavy avoidance behavior of other loons. After reporting back to Eric, he suggests the focal loon likely feels unwell, though it appears not to have any major physical injuries. He says we can take our time in observing and wait to see if it regains strength over the upcoming weeks.

July 24th, 9:00 AM

I regret my delay! While I was away monitoring loons all over Vermont, several concerned and caring volunteers kept a watchful eye on “our” injured loon. Their latest report is little changed: the focal loon is moving on the water, albeit weakly. I admit I am eager and hopeful to see some improvement. Yet, I can’t seem to locate the focal loon from shore; I see only the resident pair going about its business.

I head out in my kayak to search the perimeter, aware of how the focal loon tends to remain hidden when other loons are around. Moving clockwise, I am sure to check the shoreline diligently. Small details of the lake catch my eye, like glints of big fish chasing small fish and the striking yellow petals of a blooming water lily. Serenity. It isn’t until I round the small point that a flash of black and white draws my attention. I look through the binoculars, and see no jutting feather to signal its my loon—but this loon’s body is uncanny. As I approach, it’s the stillness that makes my stomach drop. “No feather,” I reassure myself, but the situation unfolds around me: this bird is dead, body perfectly dry but head limp underwater. Throat pierced, the flesh underneath sways with the water. I see a dark spot on the back, made only by that of a single missing feather.

Ultimately, this summer I have had the privilege of collecting data for a project that has been in existence longer than I have been alive. It is also one that has brought overwhelming success for Vermont’s loons. I recall the number of initial pairs when the project started: seven. Seven in the entire state of Vermont; that number has undergone a fourteen-fold increase and will very likely soon break 100 confirmed pairs. That is something truly amazing. Something to celebrate. I was lucky enough to be on the front lines, to observe what is the culmination of all our efforts and care that continues to catalyze this success. So, although the story with the Colby Pond Loon ended with the unfortunate loss of that individual’s life—one that impacted my own directly—it is not a sad ending overall. We will learn from this loon’s life and gain a deeper understanding of what is leading to mortality in the population. One thing is for certain, there are more loons than ever on Vermont waters and with that, a healthy competition between individuals.

Nicely written Rose.

Hi Rose,

I truly enjoyed your article, and have a question. You state that the focal loon’s throat was pierced. Do you have thoughts on how this could have happened? I’m saddened that he didn’t survive, but grateful that there are people like you who care enough to monitor them.

Hi Ginny,

Aggression between loons can occur over territory and feeding grounds. Given that Colby Pond was so small and had such high levels of loon activity, I highly suspect the focal loon died engaging another stronger, healthier loon (whose sharp beak likely caused the damage to its throat).

The question that remains is what caused this loon to be in such a weakened state and whether this was human related- such as from lead poisoning- or a natural deterioration from previous interspecifc conflicts. The focal loon will be sent to a lab for necropsy to help answer this question and when we get the results, I will be sure to update the article!

Thank you so much for your interesting reply, Rose. It makes me sad to think of the struggle that must have taken place to cost the focal loon its life. I know that nature has a way of removing the weak so that only the strong prevail, but it’s still a hard pill to swallow. I will be anxious to hear what the necropsy report entails.

Thank you, again.

Nice work Rosie! Thank you for a glimpse into your work

Nice job

Rosie!

I have seen. A loon on lake bomoseen and that surprised me

Impressive reporting

Suzanne gave me the article

Aunt Sandra

Good luck this fall

Maybe you can give me your e mail. Or phone number

I prefer to text