A Field Guide to March 2019

By Nathaniel Sharp and Kent McFarland

On Wednesday, March 20th at 5:58 PM EST spring arrives in the north. The spring equinox marks the moment the sun crosses the celestial equator – an imaginary line in the sky above Earth’s equator – from south to north. It is also at spring equinox that people all over the world can see the sun rise exactly due east and set exactly due west. While the sun may be predictable, March weather is not. In fact, March is appropriately named for the Roman god of war, Mars. March is a month of battles between warm and cold, between winter’s refusal to leave and spring’s insistence on coming. So, here are some signs of spring to look out for in this Field Guide to March.

March Migrants

© Nathaniel Sharp

As temperatures slowly rise and the days lengthen minute by minute, birds that have spent the winter in Vermont start to head northward, and birds that have overwintered further south start trickling into the state. One of the earliest migrants to arrive is often the Eastern Phoebe, frequently returning around mid-March. Male phoebes arrive first and are quick to establish territories and sing their emphatic “fee-bee” song. When females arrive later in spring, they pair up and begin constructing their nests out of mud, grass, and moss, often on human-made structures such as barns and building ledges. Unusually, one bold phoebe has managed to survive our harsh Vermont winter this year. By hawking insects over a small patch of unfrozen water near a water treatment plant in Bellows Falls, this bird has managed to weather snowstorms and sub-zero temperatures, an impressive feat for a small bird used to much warmer winters! To see photos and eBird reports of this bird, click here.

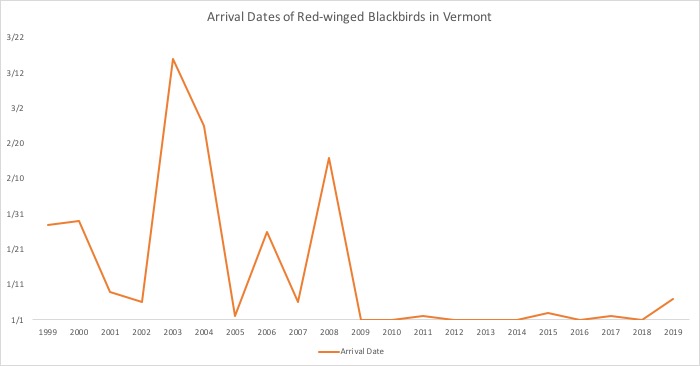

Other early migrants to be on the lookout for include American Woodcock, Red-winged Blackbird, Common Grackle, Brown-headed Cowbird, American Robin, and Song Sparrow. Turkey Vultures, one of the earliest migrants to arrive, have already been found throughout Vermont in recent weeks, and their numbers should continue to increase through March. Checklist data from eBird have shown trends of many spring migrants arriving earlier and earlier every year, so be sure to report your sightings to Vermont eBird to help scientists monitor these changes in phenology. To see what birds may be showing up in your area this spring and when, check out the helpful bar charts feature on Vermont eBird.

Skunk Oil – A Little Goes a Long Way

There is nothing like the fresh smell of a spring morning, unless, during the night, a skunk skulked about your neighborhood. The striped skunk is armed with just a teaspoon of odoriferous oil in its two anal glands, but a little bit goes a long way. These smelly yet charming mammals have recently been emerging from their winter burrows, and March marks the peak of the striped skunk breeding season. After surviving the winter cozied up in underground burrows in a state of torpor, skunks are on the hunt for a mate. Striped skunks are polygamous, and males will mate with multiple females, while a female will only mate with one male. With skunk activity picking up this time of year in Vermont, read on to learn more about the fascinating adaptations these animals have for deterring predators.

Skunk oil research has been going on for over a century as scientists have tried to determine what makes the stuff so potent that it can drive a bear away. Way back in 1896, Thomas Aldridge at Johns Hopkins University showed that humans could detect the smell at just 10 parts per billion, the equivalent to detecting just one drop of it diluted into a medium-sized, backyard swimming pool. More recently, William Wood, a chemist from Humboldt State University, pointed out that a number of chemicals have been incorrectly attributed to skunk oil over the years, and his work has now given us a fairly complete understanding of the chemical compounds and how to neutralize them.

The scent-gland secretion is a yellow oil composed primarily of volatile compounds known as thiols, and their derivatives. (A thiol is a compound distinguished by its sulfur-hydrogen bond.) Most of us immediately recognize the smell of ethanethiol (also called ethyl mercaptan), a common thiol that’s added to otherwise odorless propane gas so we can easily smell any leaks. Another thiol creates the “skunky” smell of beer after it has been exposed to ultraviolet light. The thiol derivatives present in skunk oil are not particularly odoriferous, but they are easily converted to far more potent thiols when they react with water

Skunks are reluctant to use the oils though. With only enough for a half dozen sprays at most, and a 10-day period to manufacture more, skunks will only spray if they absolutely have to. In an attempt to avoid spraying, skunks often give warning. First, they show their striped white back to warn you. This is followed by threat behaviors, like stomping with both front feet, sometimes charging forward, and then edging backwards dragging their feet and hissing. If all this fails, watch out.

Each spray gland has a nipple, and skunks can aim and direct the spray using highly coordinated muscles. A skunk can spray up to 25 feet and hit something fairly accurately up to 7 feet away. When there is a target, they can direct a fine stream right at the victim’s face. When being chased, a skunk will instead emit a foul cloud for the predator to run into.

There is one predator that remains undeterred by the odiferous oil, the great-horned owl. The small size of the olfactory lobes in their brains suggests that they have a very poor sense of smell. Some individual owls can downright stink of skunk, a common complaint among wildlife rehabilitation workers. Their nests can even smell of their musky meals. But larger-lobed mammals quickly learn to avoid the white stripe in the night.

Early Blooms

Silver Maple (Acer saccharinum) is the first maple species to bloom in North America. Flowers bloom long before leaves appear, and these delicate red blooms can appear as early as February in the southern part of the silver maple’s range and as late as May in the north. Early blooms mean that pollen is produced much earlier in spring than other trees, so this tree may be a critical pollen source for bees and other pollen-dependent insects. Most references describe silver maple as a primarily wind-pollinated species, but insect pollination may also play a role, as many bees have been seen visiting the flowers. Seeds develop quickly, within 24 hours of pollination, and shortly after they bloom, the flowers wither and the ovaries begin to swell in preparation for seed production.

Coltsfoot (Tussilago farfara) blooming along a dirt road. / © K.P. McFarland

One of the first flowers to emerge is Coltsfoot (Tussilago farfara), a species introduced from Europe that can often be found along roadways where the snow first melts away. The name “tussilago” is derived from the Latin tussis, meaning cough, and ago, meaning to cast or to act on, and harkens back to its medicinal uses. But the discovery of toxic pyrrolizidine alkaloids in the plant has resulted in liver health concerns. One of the earliest native species to flower is Hepatica. Sharp-lobed Hepatica (Anemone acutiloba) is an attractive wildflower of the deciduous forest understory. It differs from the closely-related blunt-lobed hepatica (Anemone americana) in having more acutely pointed leaf lobes. Be sure to add your sightings to our database on iNaturalist Vermont. You can also add notes about plant phenology to iNaturalist observations, so be sure to make note of whether the plant is budding, flowering, or fruiting.

Spring Sunbathers

Whether or not it comes in like a lion, March sometimes heads out like a … butterfly. On bright sunny days in late March, when the sun’s rays bring some much-needed warmth to the forests, there is a chance you may spot one of the season’s first butterflies on the wing. Unlike most spring butterflies, these aren’t freshly emerged from a chrysalis. Instead, these early spring butterflies have been tucked away in cracks and crevices where they pass the winter months in a state of torpor. Species like the Milbert’s Tortoiseshell, Mourning Cloak, and Eastern Comma utilize this strategy to survive the winter, and are the first butterflies to be seen out and about once the sun has warmed their wings. With no nectar to be found this early in spring, these butterflies are instead on the hunt for mates. You can add all of your butterfly sightings to eButterfly.

Another species that emerges on those fleetingly warm, sunny days in March is the Painted Turtle. Spending the winter under the ice of lakes and ponds, the body temperature of these hardy turtles averages just 43° F all winter long. To be active, they must raise their internal body temperature to between 63°–73° F. They achieve this by basking on logs, rocks, and other exposed surfaces. Basking not only warms up turtles so that they can be active, but also helps them capture Vitamin D from the sun to metabolize calcium to grow and solidify their shells. As temperatures are prone to shift rapidly in March, Painted Turtles often can’t maintain this temperature for long, and may not eat until May brings steadier warm temperatures. March is a dangerous time for turtles, and mortality is high during the early spring when they are living on the energetic edge of life. If you spot any early shelled sunbathers on unfrozen ponds or lakes, be sure to report them to the Vermont Reptile & Amphibian Atlas.

Where are the Loons?

Common Loon in non-breeding plumage

Nearly all of Vermont’s lakes and ponds freeze over during the winter, meaning the Common Loons that depend on them all summer long must go elsewhere to find food. Checking eBird distribution maps shows us exactly where these loons are spending their winters, and some my be even closer to Vermont than you might think! During years when Lake Champlain remains unfrozen, a few loons can often be found on the lake with flocks of ducks, looking quite different in their dull gray and white non-breeding plumage. The majority of Vermont’s loons however, appear to head to the shore for the winter, joining groups of loons from all over the northeast off the coast from the Canadian Maritimes all the way down to the Gulf of Mexico. As Vermont’s lakes and ponds start to slowly ice out, the loons that have been biding their time in Lake Champlain or the Atlantic Ocean may begin making ‘reconnaissance flights’ to inspect lake conditions. This usually only happens during years of late ice out however, so if you’d like to check in on overwintering loons, Lake Champlain is your best bet!

#1 item on my bucket list is to find a place where I can sit out in the evening & hear Loons while I’m still able. Can you help guide me?

Planning on taking a trip this year with a couple of other ladies. Hoping to rent facilities on a lake somewhere. Not locked in to location.

You won’t regret it! Here’s some resources: Our project Vermont eBird and the map from June-JUly last year is here: https://ebird.org/vt/map/comloo?neg=true&env.minX=-74.47707624804684&env.minY=43.122742107846136&env.maxX=-70.42586775195309&env.maxY=44.6331933681975&zh=true&gp=true&ev=Z&mr=6-7&bmo=6&emo=7&yr=range&byr=2018&eyr=2018. Our loon work in Vermont is on our webpage here; https://vtecostudies.org/projects/lakes-ponds/common-loon-conservation/.

there are six loons who make their home on waterbury reservoir, so little river state park.

i hear they are also present on maidstone, but i’ve only seen the ones on waterbury reservoir and marshfield pond.

Priscilla, Lake Willoughby in the Northeast Kingdom is a wonderful spot to rent a cabin/camp and hear the loons — absolutely gorgeous sunsets.