By Nathaniel Sharp and Kent McFarland

As leaves continue to fall and the first flakes begin to fly, the oncoming cold weather seems to bring nature to a standstill. On the contrary, there remains a lot to be discovered in Vermont during this transitional period. Careful observers can witness the tail end of migration as waterfowl and hawks continue their journey south, a few hardy species of butterflies and moths remain to further brighten sunny days, and avian visitors from even further north will begin to raid feeders across New England. Learn more in our Field Guide to November.

Finch Forecast

Evening Grosbeak / © Cynthia Crawford

Get ready to stock those birdfeeders! Reports have been drifting in from up north that this will be a bumper year for winter finches and other species considered to have “irruptive” (not “eruptive”, no exploding finches here!) movement patterns. Irruptive movements are dramatic and irregular migrations of large numbers of birds to areas far outside their normal winter range. Vermont experienced a similar irruption during the winter of 2017-2018, when Snowy Owls were found throughout the state until as late as May.

The yearly Winter Finch Forecast, put together by field ornithologists in Ontario, gathers information on Canadian seed crops from conifers and birch trees and uses this to anticipate the movements of a select group of “winter finches”. From sunny yellow Evening Grosbeaks and Pine Siskins to rosy red and pink Pine Grosbeaks, Red Crossbills, and Common Redpolls, this forecast predicts large movements of nearly all winter finches due to an unusually low seed crop. For decades, this seed crop was relatively cyclical, but somewhere in the last few years this cycle has gone haywire and there can now be several years between significant winter finch irruptions.

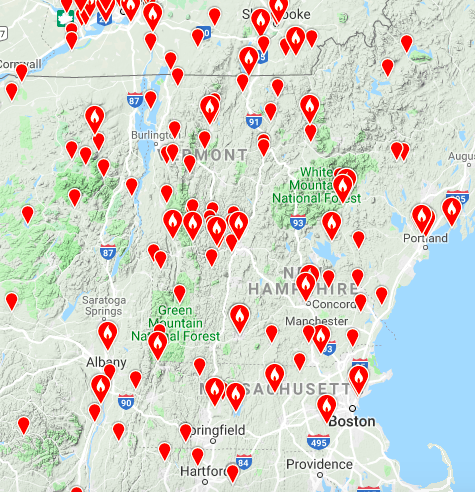

A map of Evening Grosbeak sightings reported to Vermont eBird in October 2018. Visit the map and see if they’ve moved closer to you.

Bird feeders and weedy fields will likely be the best places to spot these northern newcomers, as they will be coming so far south in search of fat-rich food that is in short supply on their usual wintering grounds. Checklists on the Vermont eBird portal have been coming in during the last days of October already reporting Common Redpolls and Evening Grosbeaks, and this movement is only expected to ramp up through November. As tempting as it can be to leave bird feeders up to attract these weary travelers, unless you are taking your feeders in every night it is best to wait until late-November/early-December to permanently maintain bird-feeding stations, as some bears are still out on the prowl for an easy snack.

Want to track the movements of these northern visitors, and see where they have been found near your neighborhood? You can check this live map from Vermont eBird to keep an eye on the progress of the big and bright Evening Grosbeaks, and you can use this tool to search range maps of all other winter finch species. Don’t forget to submit your sightings of winter finches to Vermont eBird as well!

Wingless Winter Moths

Bruce Spanworm (Operophtera bruceata) is one of the inchworms, a member of the large moth family called Geometridae (which means “earth-measuring”). / © K.P. McFarland

On even the darkest, coldest days of November, there are still signs of lepidopteran life if one looks close enough. Two moth species of the genus Operophtera, known as the Bruce Spanworm Moth (O. bruceata) and the introduced Winter Moth (O. brumata) manage to survive in conditions that would kill most other moths and butterflies. Dressed in shades of light brown and as small as a penny, these moths are easy to overlook, but what they lack in visual appeal they make up for in their fascinating morphology.

Incredibly, these moths can fly with air and body temperatures ranging from just 27 degrees Fahrenheit up to a balmy 77 degrees Fahrenheit. Generating enough warmth to power their flight muscles and get off the ground is a tall order. How do these tiny moths fly in cold conditions that make flight muscles sluggish? Morphology appears to be the key.

The male Bruce Spanworm Moth has one of the lowest wing-loads (total weight divided by wing area) of any moth measured. This both reduces the number of wing beats and lowers the energetic cost required to sustain flight. These little moths also have one of the highest flight muscle to body size ratios. These surprisingly bulky muscles are able to compensate for the reduced muscle contraction associated with cold temperatures and continue to generate enough tension to power each wingbeat. Powerful muscles, combined with efficient wings allow these moths to operate in very low temperatures as they seek the scent of females wafting pheromones.

The female Bruce Spanworm Moth has also adapted to survive in low autumn temperatures, but in a completely different way. They are flightless. The female Bruce Spanworm Moth has no wings at all while the female Winter Moth retains vestigial, yet nonfunctional, wings on her back. When the females emerge in October and November, they laboriously crawl up the lower trunk of a host tree, where they solicit flying males with a chemical cocktail.

A flightless lifestyle holds several advantages for female Bruce Spanworm Moths. Without bulky flight muscles weighing them down, females are able to dedicate over 60% of their total body weight to egg production, holding an average of 143 eggs. A flight model by James Marden, a biologist at Penn State University, suggested that if a female were to retain enough flight muscle to sustain weak flight at optimal temperatures, she would experience a 17% reduction in egg-carrying capacity. In order to sustain powerful flight, an 82% reduction would need to occur in order to make room for the powerful flight muscles required.

Flying and crawling along through the woods during some of the coldest months of fall surely must have some advantage for these moths, right? It is likely that these adaptations occurred in response to a powerful natural selection force, predation. By late October and November, most of the insectivorous birds have migrated south and bats have migrated or gone into hibernation for the winter. With most significant moth predators out of the picture, these moths have free-reign of Vermont’s forests. If you happen to spot one of these fascinating moths, snap a photo and submit your sightings to iNaturalist Vermont, a project of the Vermont Atlas of Life.

Final Flights of the Butterflies

A Clouded Sulphur (Colias philodice) takes a break in the high peaks of the Presidential Range, NH. / © K.P. McFarland

While the days are certainly getting chillier, every now and then there comes a sunny, warm(ish) day in November when you can spot a few brightly colored butterflies fluttering about. Orange and Clouded Sulphurs are most often found flying in fields and open areas, while Question Marks and Eastern Commas punctuate the woodlands of Vermont. These hardy butterflies are some of the last species we will see until next March, so get out and enjoy them while you can!

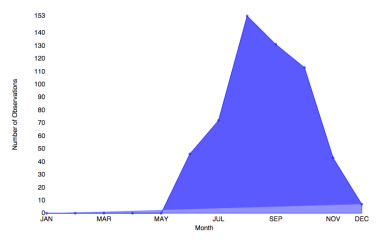

Clouded Sulphur flight season in Vermont from e-Butterfly.org data. Some are found in the Champlain Valley as late as early December.

For better or worse, we could be seeing butterflies later into fall and earlier in spring, as flight periods have been lengthening in recent years. A study in Canada has shown that the timing of butterfly flight seasons responded to temperature both across the landscape (variation in average temperature from site to site in Canada) and across time (variation from year to year within each individual site). These researchers found that given the widespread temperature sensitivity of flight season timing, with increased warming we can expect long-term temporal shifts of 2.4 days for every 1.8 degree F change in air temperature for many if not most butterfly species.

Help us document the late season fliers!

When you find a November (or even December!) butterfly, snap a photograph and submit it to e-Butterfly.org, a project of the Vermont Atlas of Life. Let’s see who can find the latest butterfly in 2018!

Autumn Odonates

Autumn Meadowhawk / © Susan Elliott

Winning the award for most appropriately named dragonfly is the Autumn Meadowhawk which can be found, you guessed it, hawking for insects in meadows during autumn. Of the 101 dragonfly species in Vermont, the Autumn Meadowhawk is one of the most frequently observed, largely due to its lengthy flight season which begins in July and lasts until late November. Of the six red meadowhawk species found in Vermont, this species is the only one with yellow legs, and is also most likely the last dragonfly to be seen in Vermont until next April. Throughout November, if you happen to see a dragonfly drifting past a hawkwatch site or baking in a warm patch on a sunny day, chances are you’re looking at an Autumn Meadowhawk! As always, submit any sightings of this species to iNaturalist Vermont to add your very own data to the Vermont Damselfly and Dragonfly Atlas, a project of the Vermont Atlas of Life.

Snow Flocks

A flock of Snow Geese takes flight at Dead Creek WMA in Addison County © K.P. McFarland

Perhaps nothing signifies the changing of the seasons more than the honking of Canada Geese flying in V-formation on their way south, but how often do you double-check those migrating flocks? Not all flyover goose flocks are Canada Geese, and it is always worth checking these high-flying V’s for the characteristic white bodies and black wingtips of Snow Geese. Of course, one of the most well-known sites for viewing these fall migrants is the Goose Viewing Area along Route 17 in Addison. If you can’t make the trip out to Dead Creek WMA in Addison, it is worth keeping an eye on the sky in the hopes that you may spot a Snow Goose flyby. If you are at the Goose Viewing Area and there are no geese to be viewed, heading a little farther south, down Route 22A to Gage Road, can occasionally reveal hidden flocks of geese originally obscured by a dip in the landscape. These flocks, numbering in the hundreds or even thousands, are fairly mobile and travel throughout this area in search of the most productive fields. The best way to keep track of their movements is to use this live map of Vermont eBird sightings to see where the flocks have been spotted most recently, and don’t forget to submit your own sightings to help out other hopeful goose-viewers!

Getting Sleepy?

Black Bear observed and reported to iNaturalist Vermont by Kyle Jones.

As surprising as it might seem, Black Bear aren’t actually true hibernators. Sure, their respiration and metabolic rates decrease during winter sleep, but their body temperature still remains close to normal. Unlike a true hibernator, a denning bear can be easily awoken within moments, while a true hibernator can take up to several hours to come to its senses.

In order for an animal to be considered a ‘true’ hibernator, its body temperature, respiration rate, and metabolic rate must all significantly decrease during winter. A true hibernator found in farm fields, along roadsides, and (much to the chagrin of gardeners) in backyards is the Woodchuck. These large rodents are capable of decreasing their resting heart rate from 80 beats per minute to just 4 or 5 bpm when in hibernation. Their body temperature, which is usually around the same as a humans, decreases to a mere 38 degrees Fahrenheit. Like other rodents, a Woodchuck’s powerful incisors grow continuously, and are maintained by their constant gnawing. This growth is stunted during winter so the incisors don’t grow out of control. True hibernators do in fact wake up every few weeks to nibble on food, and in the case of the Woodchuck, use the underground outhouse.

Food supplies are the most critical factor determining when Black Bears den each fall. When food is abundant, they’ll continue eating throughout the snows of November and into December. When autumn foods are scarce, most bears den by mid-November. Dens are commonly brush piles, and occasionally can be caves in rocky ledges, hollow trees or logs, a sheltered depression or cavity dug out at the base of a log, a tree, an upturned root, or simply a hole dug into a hillside. Male bears aren’t particularly choosy with their denning sites, and can be found denning in just about all of the above scenarios. Females, however, are a little more particular, selecting protected sites and lining them with stripped bark, leaves, grasses, ferns, or moss.

Zombie Aspen Leaves

Quaking Aspen Leaves / © Bryan Pfeiffer

While walking outdoors in autumn, leaves crunching underfoot, be on the lookout for the fallen yellow leaves of aspens and cottonwoods. These rounded leaves with pointed tips may appear dead, but looking closer can reveal a small patch of life on some leaves. These undead leaves have a stripe of green radiating from the midrib that sets them apart from the other brown, orange, and red tones of fall. In Vermont, these strange “zombie leaves” mostly belong to Quaking Aspens (Populus tremuloides), but can also be Big-toothed Aspen (P. grandidentata) and rarely Eastern Cottonwood, (P. deltoides). So what is causing this strange phenomenon?

Bryan Pfeiffer explains the mystery of these leaves in his blog.

Fascinating! So happy to be reading this! and so proud of you, Nathaniel.

Along with House Finches, Juncos, White Crowned and White Throated Sparrow flocks we saw our first ever Northern Cardinal in mid-October in Mount Holly. It was a female and she visited out feeder for only one day but it was a surprise.

Nice! If you are inclined, we collect bird sightings on our Vermont eBird (https://ebird.org/vt/home) or on the Vermont Atlas of Life on iNaturalist (http://www.inaturalist.org/projects/vermont-atlas-of-life). Check it out and consider sharing your observations too!

It is discouraging to see a professional organization like yours that must know that congregating animals improves the probability that diseases will be transmitted Still enthusiastically encourages feeding. Do the right thing!

We remind folks all the time to follow what the Cornell Lab of Ornithology recommends for cleaning feeders and feeding areas (https://feederwatch.org/learn/feeding-birds/safe-feeding-environment/ and https://feederwatch.org/blog/cleaning-preventing-disease/). I am not aware of any peer-reviewed work suggesting that avian disease at songbird feeding stations is a source of population control besides perhaps conjunctivitis with introduced House Finches, on a density dependent basis. We are always interested in new science and sharing it if you are aware of any. Thanks.