Field Guide to September 2019

Suddenly, you realize it’s September. It can happen almost anywhere. On some summit with Broad-winged Hawks kettling above, and insects like Monarchs and Green Darners gliding southward, often at eye level. Or even at night when you step outside and hear a few contact calls high above from songbirds as they migrate southward on the latest cold front. Here is your field guide to life on the move, and some natural history tidbits to look for this fall.

Humming Along

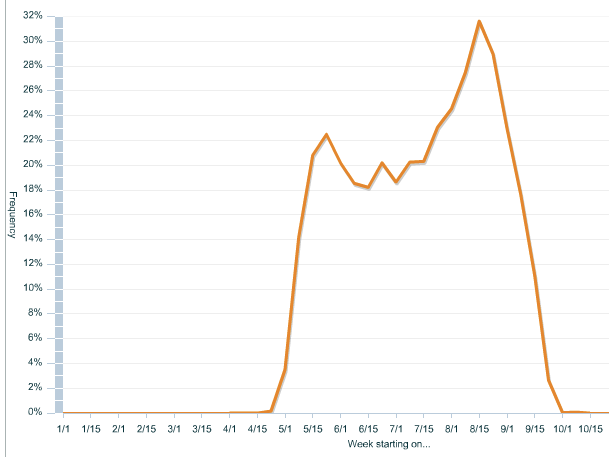

Weighing about as much as a dime, Ruby-throated Hummingbirds fly non-stop over a span of 24 hours across the Gulf of Mexico each spring and fall. Large numbers of these tiny birds have been observed flying low over the waves trying to make landfall in spring. Here in the Northeast, when the flowers stop blooming and insects stop flying, Ruby-throated Hummingbirds have already gone south. Some adult males start migrating south as early as mid-July, but the peak of southward migration is August and early September, and by October they’re all gone.

Most, if not all, of the hummingbirds at your feeders in September are migrants and not the same individuals you’ve watched all summer. Since they all look alike, it’s difficult to know for sure, but banding studies have shown the turnover. It’s not necessary to take down feeders to force hummingbirds to leave, and in the fall all the birds at your feeder are already migrating anyway. Keep them up as long as you can and just maybe a wayward rare species will find them.

Where do they all go? There is some evidence that more of them travel around the Gulf of Mexico in fall migration, rather than cross it as they do in spring. They’ll spend the winter in Mexico and Central America. Then they’ll make the round trip back in April and delight us once again with their bright colors and active flights after our long white winter.

Keep an eye out for migrating Ruby-throated Hummingbirds this month, and make sure you add your sightings to Vermont eBird and help track their phenology.

Nighthawk Watching

On warm summer evenings in the breeding season in Vermont, Common Nighthawks once roamed the skies over treetops, and towns.Their sharp, electric peent call was the first clue that they were overhead. At dusk, these long-winged birds flew in graceful loops, flashing white patches out past the bend of each wing as they chased insects. Those days are mostly gone now, but in late August / early September, the careful observer can still witness their spectacular flight here in Vermont as Nighthawks whirl southward on their autumn migration.

Although most often seen migrating at dusk here in Vermont, Common Nighthawks migrate at all hours of the day, often in large flocks, on one of the longest migration routes of any North American landbird. Many travel overland through Mexico and southward through Central America, while others pass through Florida and across to Cuba southward, flying over the water to reach their wintering grounds in South America thousands of miles away. Learn more about Nighthawk migration on the VCE blog.

Daring Darners on the Move

A mere three inches long and weighing just four-hundredths of an ounce, it glides on four wings thousands of feet in the air. With hundreds, maybe even thousands, of other individuals and little fanfare, it left a small Vermont pond and struck southward. Autumn is a season of migration and this Common Green Darner dragonfly is headed to warmer waters thousands of miles away, perhaps as far as Central America or the Caribbean.

Dragonfly migrations have been observed on every continent except Antarctica, with some species performing spectacular long-distance mass flights. A dragonfly called the wandering glider is the long-distance champion, making flights across the Indian Ocean that cover twice the distance of monarch butterfly migrations. In North America, dragonfly migrations occur annually in late summer and early fall, when millions of insects, hatched in the north, move southward. Of North America’s over 330 dragonfly species, only nine regularly migrate.

North America’s most abundant and widespread migrant dragonfly is the Common Green Darner. In the spring, just after the ice has disappeared from the ponds, green darners suddenly appear, well before any local dragonflies have emerged. These are migrants from the south, having flown from perhaps Florida, the Caribbean, or Mexico. They breed soon after arriving, and their nymphs develop quickly in water warmed by the spring and summer sun. Many adults emerge from the ponds in August. They feast on insects to pack on fat, perhaps increasing their weight by up to a third. But instead of breeding at their natal site, they begin a southward migration that may span a month or even longer.

VCE and colleagues from the University of Maryland, and Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, recently published a paper that explains how the Common Green Darner completes its annual migration. Their paper published in Biology Letters describes the full life cycle of this dragonfly, including an astonishing multi-generational migration of over 600 km (373 miles) on average, with some individuals covering more than 2,500 km (1,553 miles)!

Migrating Monarchs and Citizen Science

How you can help document their migration habitat!

Right now, in one of the most dramatic migrations on the planet, the latest generation of monarch butterflies to hatch in the Northeast is migrating to Mexico. Each winter in the transvolcanic mountains not far from Mexico City, the entire population of Monarch butterflies from east of the Rocky Mountains congregates in the trees. These are small peaks ranging from 7,800 to 11,800 feet in elevation and covered with Oyamel Fir trees (Abies religiosa), a species closely related to the Balsam Fir (Abies balsamea) found on the mountain tops here in northeastern North America. A site may contain up to 4 or 5 million monarchs per acre and cover as little as one-tenth up to 8 acres of fir forest.The butterflies arrive from the north in November to late December and hang out on the trees metabolizing fat reserves that they have built up during migration. Remarkably, they actually gain weight on migration and arrive on the wintering grounds with fat reserves for the winter, unlike songbirds, which require huge fat stores to burn on migration.

The winter generation lives up to 8 months while the successive spring and summer generations are lucky to live 5 weeks. It takes up to 6 generations of spring and summer Monarchs to produce the final “super-Monarch” that migrates to Mexico in autumn and then back to the southern United States in spring.

Along the way, stopover habitat is critical. Southbound monarchs find roosting sites that provide overnight shelter from wind and rain, and a place to warm up in the morning, such as hollow trees. They also seek out nectar sources, where flowers abound. Hundreds or even thousands of monarchs may congregate at a single roost site. While we have a good idea of what makes for a good migratory roosting site, the criteria which determine where monarchs actually congregate to roost are poorly understood.

Scientists at the University of Maine’s Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit have devised a clever – yet still experimental – way to predict where migrating monarchs will roost. First, they studied the characteristics of known roosting sites. They identified 15 environmental variables that most of these sites shared. Then, they evaluated a map of the northeastern US, pixel by pixel, and calculated the likelihood that the habitat in each pixel matched the qualities of the known roosting sites. They generated a map showing the probability that a pixel-sized area would host a monarch-roosting site.

This is where you come in. Having modeled the most likely places to host roosting monarchs, the scientists need to test their model. They are asking citizen scientists to visit the sites their model identified and complete a survey about the habitat they find. This will help them refine their model and make the most accurate prediction of where migrating monarchs will roost, how much quality habitat is available to them, and where quality roosting sites are needed.

To learn more about this project, and sign up to participate, visit https://umaine.edu/mainecoopunit/monarch-model-validator/. Maybe you’ll get lucky and see hundreds or thousands of monarchs gathered at a migratory rest stop!

The Last Flower

Yellow and spindly, it is the lonely flower of autumn. Even after the leaves have fallen and the Monarchs have left us for Mexico, Witch Hazel is acting like it’s spring outside. In barren woods this shrubby tree attracts some of the year’s final pollinators—the late-season flies and moths that have few other options for nectar. And once pollinated, the flowers take a full year or more to mature into seed-bearing capsules. That’s when the fun begins. In the fall, Witch Hazel ejects its seeds in a subtle woodland fusillade. Or, as David Taft writes in The New York Times: “The clattering seeds and popping pods fill the woods with vibrancy.”

What are Those Red Bugs?

Starting in mid‑July, Boxelder Bugs (Boisea trivittata) are in seed-bearing (female) Boxelder Trees where they lay eggs on trunks, branches, and leaves.They feed on the seeds on the ground in the spring. During late summer and fall, they start to leave the trees where they were feeding in search of a spot to overwinter. You may see them massed together on warm, exterior walls, rocks and tree trunks. Although you can find nymphs during fall, only fully grown adults survive the winter. They are most abundant during hot, dry summers that are followed by warm springs. As the weather cools, they find cracks and spaces around homes, outbuildings, rocks, and trees. In some cases they end up inside buildings (like your house), where they’ll spend the winter. But fear not, come spring, they’ll vacate their winter hibernation locations to feed and lay eggs on maple or ash trees.

Radiant Red

Speaking of red, bright red leaves under a clear blue sky are spectacular to see. But what is beauty to us may be survival to a tree. As the green chlorophyll in leaves breaks down without replacement, we begin to see the underlying orange carotenoids and yellow xanthophylls. These pigments help capture light energy during the growing season. But unlike yellow and orange pigments, red anthocyanins are made during fall leaf senescence. They are manufactured from sugars found in the leaf, produced in greater amounts during cooler nights and sunny days. When a hard freeze comes along, production ends. Why would a tree use energy to make a pigment in a leaf that is about to die and fall off? Find the answer on the VCE blog.