What Three Decades of Monitoring Birds Reveal About Our Changing Forests

Blackburnian Warbler © Atticus Soehren

Atticus Soehren is a senior at the University of Pennsylvania, majoring in biology and minoring in data science and analytics. He has always had a passion for birds, climate, and the outdoors. Here he shares the results of his internship this summer under Michael Hallworth’s supervision, analyzing data from the Vermont Forest Bird Monitoring Program.

Deep in the Vermont forests, the flute-like call of the Hermit Thrush drifts through the understory and the Blackburnian Warbler’s song carries from the canopy, both reminders of the diversity and complexity woven into Vermont’s forest ecosystems. But this dawn chorus of breeding birds is shifting.

For decades, volunteers for the Vermont Forest Bird Monitoring Program have woken up early and counted these species across the state. Little did they know that over the last few decades, they’ve witnessed a subtle change in voices across the landscape. Now, as Vermont warms and winters shorten, we asked:

How are Vermont’s forest songbird species responding to ongoing climatic changes, and what might those patterns mean for the forests they depend on?

Using more than 30 years of bird survey data, we examined how warming springtime temperatures affect the probability that Catharus thrushes and several warbler species occupy interior forest patches across Vermont. We now have preliminary results of how these species have responded to a changing climate over the past several decades across the state.

American Redstart © Atticus Soehren

The Canaries in the Coal Mine: Thrushes and Warblers

Since 1989, the Forest Bird Monitoring Program (FBMP) has surveyed Vermont’s birds that breed in interior forests. The surveys, which occur annually, provide a clear window into how the state’s forests, and the birds that depend on them, are changing. Long-term datasets like these are rare, and their value continues to increase, as the past three decades have seen the fastest rate of climate change on record, and especially in New England .

In Vermont, ongoing climate change will undoubtedly reshape forests from the canopy down to the soil. The species groups we focused on—thrushes and warblers—include closely related species that often share habitats and compete with one another for resources. Because they live and breed in similar forest conditions, even subtle shifts in temperature, precipitation, or habitat structure could influence where each species occurs, making them powerful indicators of ecological change.

By comparing their occupancy patterns through time, we can begin to answer urgent questions:

- How has a changing climate affected the distribution of Vermont’s forest interior birds?

- Do closely-related species respond similarly to climate change?

How We Analyzed the Data

Counting animals is hard and we rarely detect everything. We often identify and tally bird species at a survey location by sight or sound. But during a 10-minute point-count, some species might not sing, or may be busy feeding nestlings instead of singing from their favorite perch. They may be missed during the count even though they were present at the time of the survey.

To account for this imperfect detection, we used occupancy models: statistical tools that separate true changes in where bird species occur from the natural variability in the detection process. We won’t get into the nitty-gritty details of the analysis itself, but suffice to say, using this method, we get a more accurate view of how species’ distributions have shifted over time.

For our analysis, we focused on two groups of species, thrushes and warblers, across 34 survey locations throughout Vermont. For each species, we estimated the trend in site occupancy over the last three decades. We used those trends, along with rates of climate and precipitation change, to better understand how these birds’ relationships with Vermont’s forests have changed over time and how species may respond to continued environmental change.

Yellow-rumped Warbler © Atticus Soehren

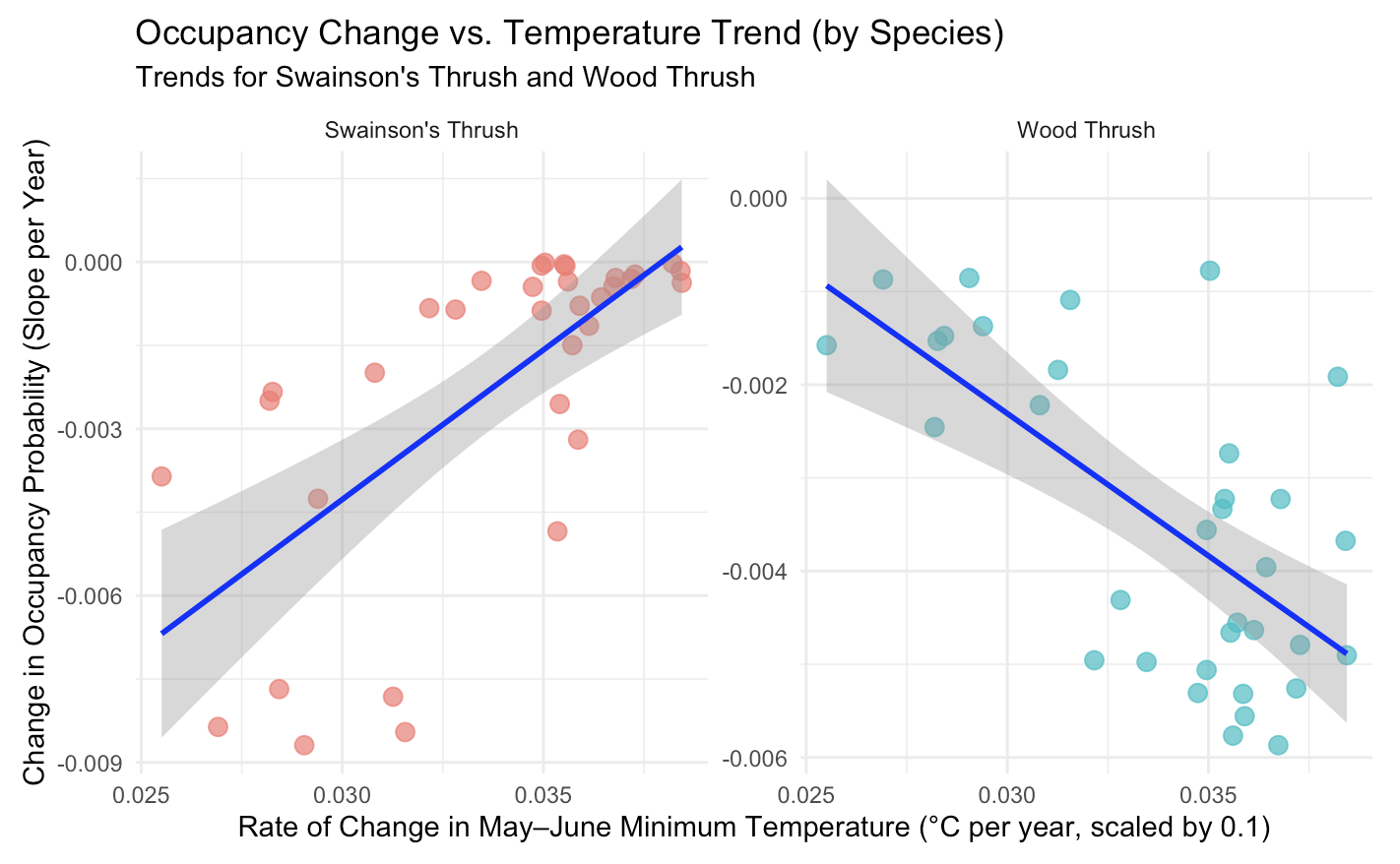

Different Stories Among Vermont’s Thrushes

Our analysis revealed that the thrushes are responding to warming in distinct ways. The Wood Thrush, for example, showed the steepest declines, with occupancy decreasing in areas with warmer springtime temperatures. Similarly, both the Hermit Thrush and the Veery occupancy probabilities tended to decline as the minimum springtime temperatures rose, though their trends were weaker and more variable across the state.

In contrast, the Swainson’s Thrush, typically associated with higher elevation and cooler forests, showed the opposite pattern. Its probability of site occupancy increased with warming spring temperatures, suggesting that this species is expanding into areas that are becoming more suitable as conditions shift upslope.

Figure 1. Occupancy change vs. temperature trend for Wood Thrush and Swainson’s Thrush. Each point represents a survey site, with the blue line showing the relationship between local temperature change and the annual rate of occupancy change.

These mixed results highlight that even closely related species, occupying similar habitats, may respond to climate change in very different ways, depending on where they live along Vermont’s elevational gradients.

Ovenbird © Atticus Soehren

Winners and Losers Among the Warblers

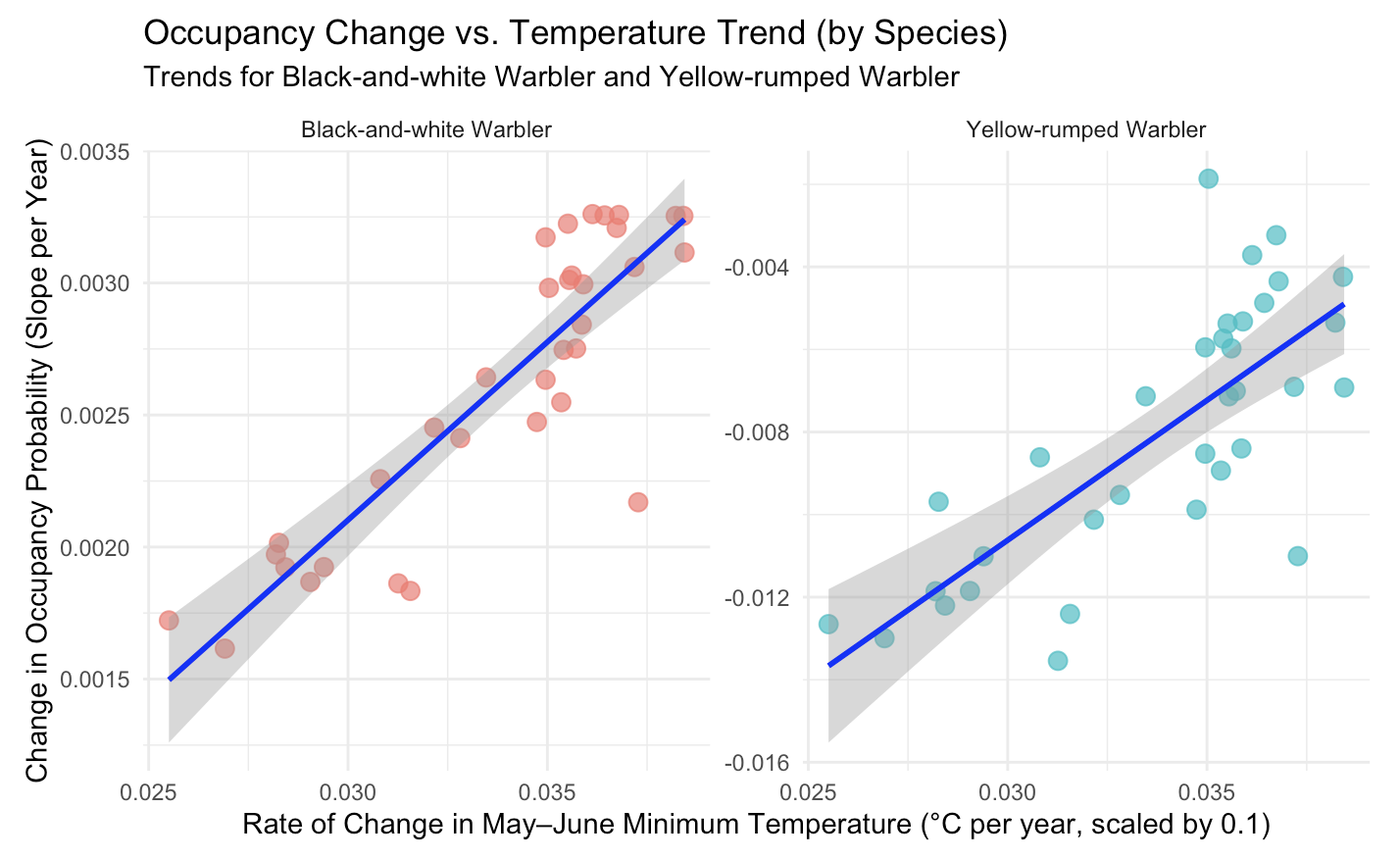

The warbler response to a changing climate was equally variable and complex. Species such as the Black-and-white Warbler and Yellow-rumped Warbler showed increased occupancy in areas with greater rates of change in spring temperatures, suggesting that species inhabiting cool-temperate forests may benefit from warmer springtime conditions or shifts in forest composition.

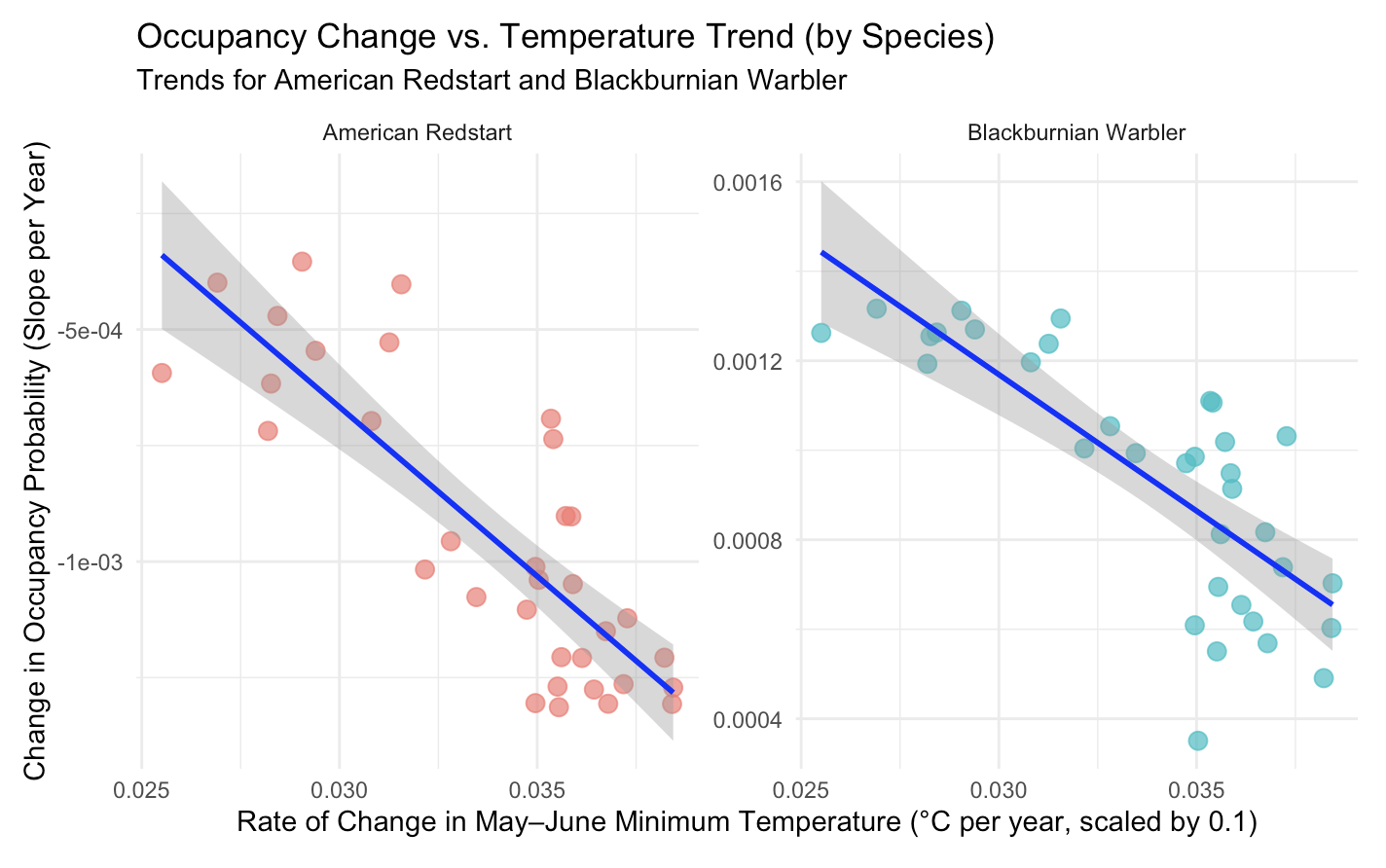

Other species, however, showed a decline in site occupancy in areas with higher rates of change in springtime temperatures. The American Redstart and Blackburnian Warbler both exhibited negative relationships between occupancy and increasing spring temperatures. Interestingly, the Ovenbird, a ground-nesting species that forages on the ground and lower vegetation, also showed a similar pattern as the American Redstart and Blackburnian Warbler, which nest and forage in the canopy. These species are typically associated with cooler, more mature forests, so the patterns we observed may reflect subtle habitat changes tied to a changing climate and forest succession. More research is needed to disentangle the drivers of change we highlight here.

Not all warblers showed significant responses, however. Four of the nine warbler species—Black-throated Blue Warbler, Black-throated Green Warbler, Common Yellowthroat, and Northern Waterthrush—had no significant association between site occupancy and change in springtime temperature between 1989 and 2024.

Figure 2. Change in site occupancy in response to the rate of springtime temperature for Black-and-white Warbler and Yellow-rumped Warbler between 1989-2024. Each point represents a survey site, with the blue line showing the relationship between local temperature change and the annual rate of occupancy change.

Figure 3. Change in site occupancy in response to the rate of springtime temperature for American Redstart and Blackburnian Warbler between 1989-2024. Each point represents a survey site, with the blue line showing the relationship between local temperature change and the annual rate of occupancy change.

Black-throated Blue Warbler © Atticus Soehren

These contrasting patterns, along with the species that showed no significant responses, point to a gradual reshaping of Vermont’s bird community. Some species are responding to a warmer, more mixed landscape, while others are potentially losing ground as their preferred climate and/or habitats shift northward or upslope.

Taken together, the results suggest a consistent ecological signal: Vermont’s iconic bird species are responding to our changing climate. We found in our preliminary analysis that the site occupancy of species associated with cooler forests is changing most where the change in spring temperatures has been greatest . This pattern mirrors trends seen elsewhere in the Northeast and highlights how Vermont’s long-term bird data can reveal early indicators of climate-driven changes long before physical changes are visible in the forest itself.

From Data to Decisions about Vermont’s Conservation Future

Results like these show why long-term monitoring is so important. The Forest Bird Monitoring Program gives us a rare opportunity to evaluate how Vermont’s forests and the wildlife within them are changing over time. As challenges like climate change and habitat loss continue to shape the landscape, these data help scientists and land managers make informed conservation decisions, with each year of careful observation adding another piece to the puzzle.

We’d like to thank the volunteers who contributed data over the years, and Rick Bowe for his continued enthusiasm and support, and for helping to bring this project together.

Very interesting report. Thank you for sharing it