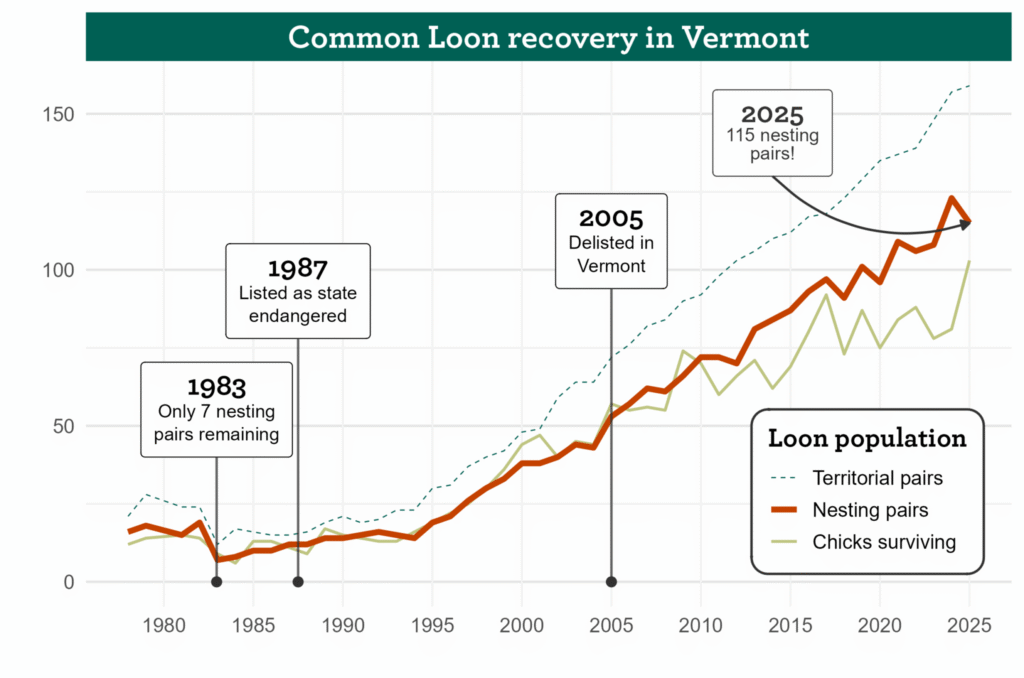

We’re proud to say the number of nesting loons in Vermont has risen dramatically from seven pairs when our recovery efforts began 40 years ago, to more than 400 adult loons today. Listed as state endangered in 1987, the Common Loon was removed from the Vermont Endangered Species List in 2005.

Another Banner Year for Vermont Loons in 2025!

Thank you to this community of big-hearted helpers—volunteers, donors, and everyone who contributed support—together we made 2025 another banner year for Vermont loons.

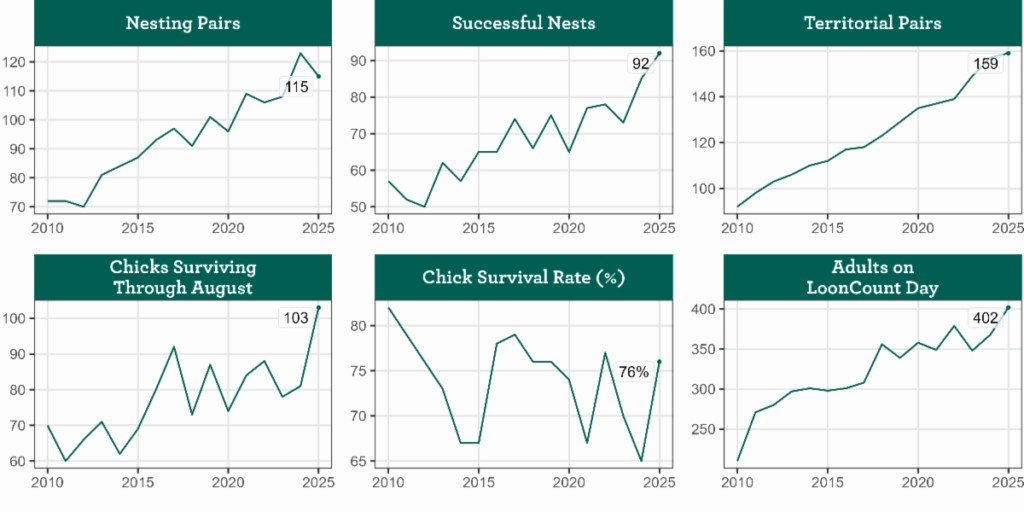

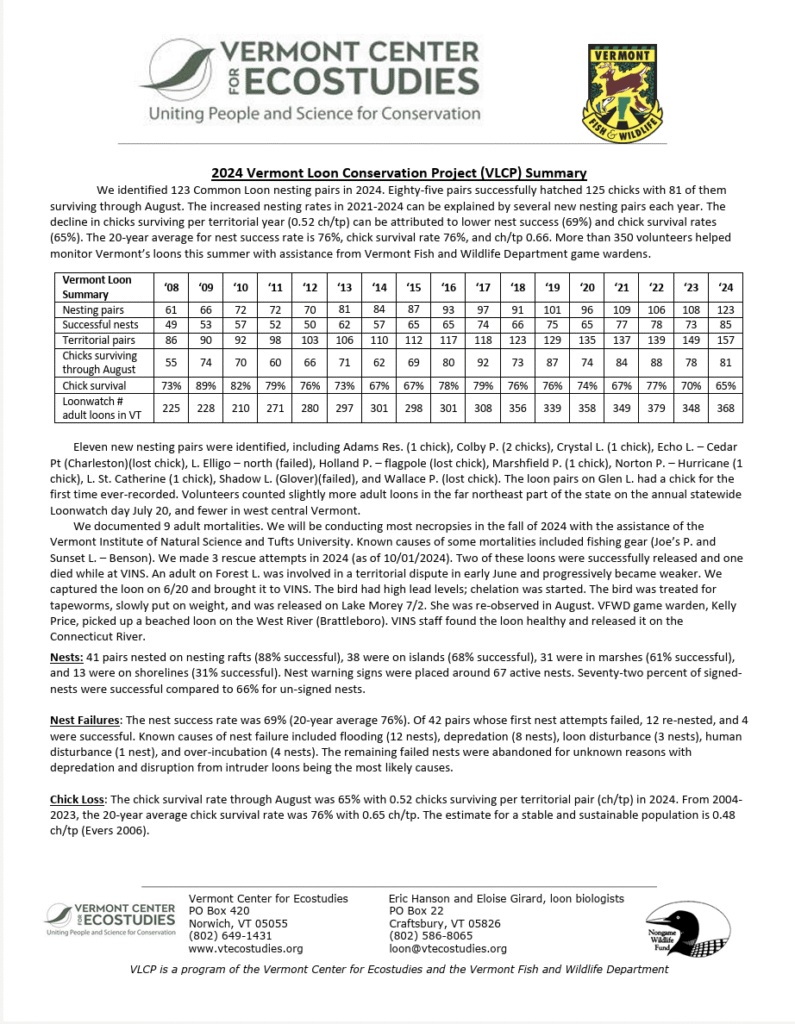

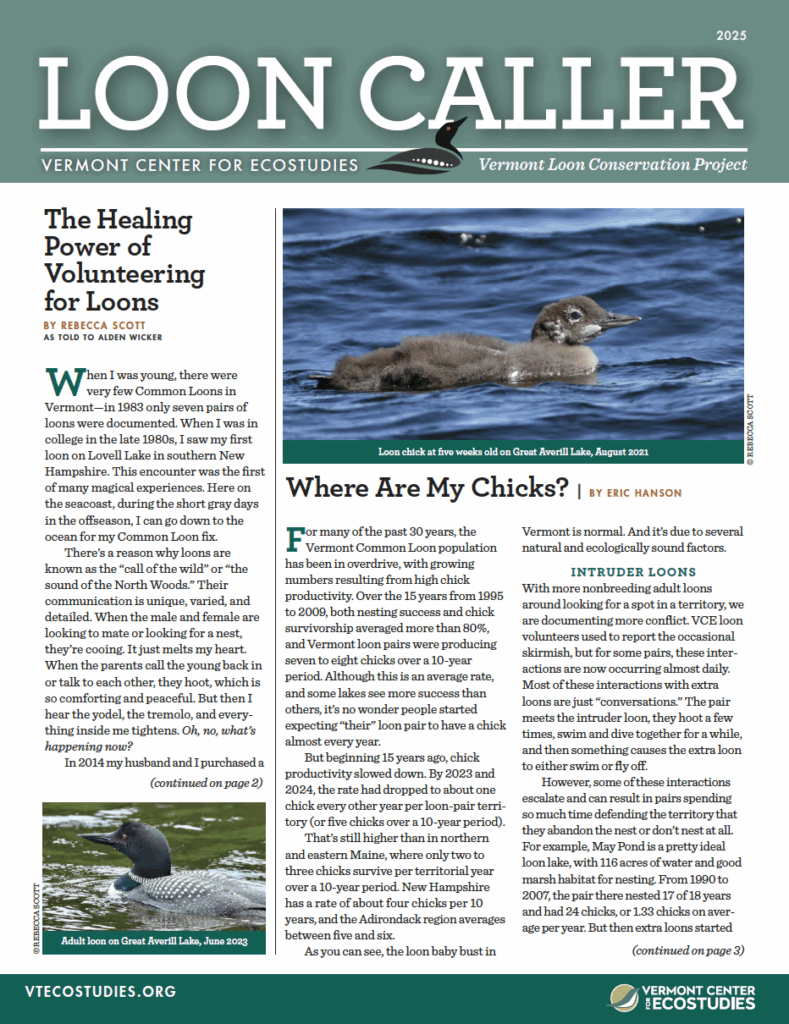

Over 350 volunteers helped the Vermont Loon Conservation Project (VLCP) and the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department monitor Vermont’s loons this summer, and collectively we identified 115 Common Loon nesting pairs.

The north central part of the state (from Ryegate to Eden) is experiencing a loon boom; 182 adult loons were counted on LoonCount day in July, over 30 more than in previous years.

Even more exciting: for the first time, loon chicks hatched out and survived on Shadow Lake in Glover and the Cedar Point territory of Echo Lake in Charleston—both had failed nests in 2024. We documented three new nesting pairs at Colchester Pond, Lake Fairlee, and Long Pond in Milton.

After a dip in 2023 and 2024, we’re back up to a higher-than-average nest success rate—a record 103 chicks survived through August, and 15 fewer nests failed this year compared to last year. Loons are resilient! Of the 29 pairs whose first nest attempts failed, 11 re-nested, and six were successful.

In the past, humans caused a large portion of nest failures, but our signage and education seem to be working. This year, only one nest failed because of human disturbance. The rest failed because of flooding, depredation, loon disturbance, and over-incubation, in that order. Rafts, which can rise with changing water levels and hide nests from predators, continue to be the safest place to nest, and the shore the least safe. Eighty-eight percent of the forty-three pairs that nested on rafts were successful, 82% of the 34 island nests and 28 marsh nests were successful, and only three of the 10 shore nests were successful.

We conducted nine successful rescues in 2025, releasing six of them. Three loons crash landed and were moved to nearby waterbodies, two loons likely landed on ponds too small to take off from, and two were iced in. All appeared to be healthy upon release. The other three unfortunately died after capture. We documented nine adult loon mortalities—two died from lead poisoning from fishing gear, one from a boat hit, three from fights with other loons, one from a bald eagle, and one from an internal infection. One loon had been banded in Moultonborough, NH in 2015.

Eagles and territorial disputes likely caused the loss of most—if not all—of the chicks. Although losing chicks can be distressing for those invested in their local loon families, it’s a sign of a healthy population. As the population continues to grow and then stabilize, and more unpaired loons try to find habitat, we anticipate the chick survival rate will go down again—a stable and sustainable population of loons has an estimated chick survival rate of 0.48 per territorial pair (about one chick every other year) and we’re at 0.65.

With this success, as we look toward 2026, we will reassess our deployment of rafts and whether more loons should be encouraged to nest naturally. We will also continue to encourage anglers to fish lead-free and lakeside owners to rewild their shorelines. A healthy lake for loons is a healthy lake for eagles, otters, fish—and all the humans—who enjoy them!

Download the full report below.

Other Measures of Loon Conservation Success

- Over 60 Common Loons, which wouldn’t have otherwise survived, were rescued by VCE, state game wardens, or volunteers since 2002.

- Adding floating nest warning signs around sites at high risk of human disturbance increased nesting success from 55% to 81%.

- The VCE loon biologist and volunteers monitor more than 130 lakes up to six times per month and another 70 lakes at least once during the summer. Their contributions include:

- the discovery of between three and seven new territorial and nesting pair each year

- more than 850 hours assisting with 100 plus loon rescues

- assisting with nest warning signs and nesting rafts on more than 40 lakes